Analog Corner #16

(Originally published in Stereophile, November 12th, 1996)

I'm tired of reading hacks who predict the merging of audio, video, and computing. You know, the integrated "multimedia" living-room package—Dad sitting before the theater-size flat screen doing his taxes, Mom "surfing" the Internet for recipes, Junior downloading instructions for building pipe bombs—that sort of thing.

It ain't gonna happen, okay? Not when Dad can have a $1500 PC in the basement home office, not when Mom can have a $1000 PC in the kitchen (Dad's always has to be bigger—it's a "Family Values" clause in the Contract On America), and Junior can have one in his bedroom—and everyone can attend to his or her own business in private. Why would you want to tie the whole thing together in one place so that everyone but the person hogging the monitor can get ticked off waiting for screen time?

No, the family room is for family business, like watching television and movies. I have running water in my kitchen—does that mean I should rig up a toilet in the middle of the room?

I feel better now. But how about this? In October, I complained to you about how difficult it was to find out what's being issued on vinyl in this country. I wrote: "I got Elvis Costello's All This Useless Beauty on domestic vinyl, but you wouldn't know it existed from the ads, not to mention from a perusal of the bins at most stores."

So last week I get a call from a publicity guy at Warner Bros. telling me how cool The Tracking Angle's Van Dyke Parks cover story was, blah blah blah, and that Warners was about to release a new Robyn Hitchcock album on both CD and limited-edition LP, and that he'd send me one for review because he knows how much I like vinyl, and that the LP, Mossy Liquor, contains different material from the CD, Moss Elixir.

I said, "You know, that's great, but the problem is, if you hadn't called to tell me the LP was being released, I probably would never have known about it. I mean, if someone hadn't called and alerted me to the vinyl of Elvis's All This Useless Beauty, I never would have known about that."

"Wait a minute!" the Warners publicist shot back. "That was released on domestic vinyl?"

Need I say more?

Or how about this one: I got a call today from a record dealer who shall remain nameless. He said to me, "Hey, you have Neil Young's Broken Arrow on vinyl, right?"

"Yes," I replied.

"Well, where'd you get it?"

"Carl Baugher got it for me at Lou's in Encinitas. Why?"

"My WEA rep told me it had been canceled and never released."

"Then I must be having an acid flashback, because I have it and I've heard it. It's mastered by Chris Bellman at Bernie Grundman Mastering, it's all-analog mastered from the original two-track analog master tapes, and it sounds [expletive deleted] awesome! Gigantic soundstage, killer cymbal sound. Much better than the HDCD$r CD!"

I got out the LP and read him the numbers so he could stick it in the rep's face. A few minutes later he called again. "Are you sure it's domestic vinyl? The guy says it was never released."

At this rate, folks, we can all kiss our black vinyl butts goodbye.

Bob Ludwig gets lathed

That's one side of this schizophrenic vinyl revival. The other side is some recent news from Bob Ludwig. When I received Carl Baugher's review copy of Rage Against the Machine's new LP, it included a Bob Ludwig mastering credit. "Impossible," I told Carl. "Ludwig doesn't have a lathe at Gateway. He set up a digital mastering facility with no lathe. They probably just copied the credits from the CD booklet."

I called Ludwig, and guess what? I was wrong. He's got his Neumann VMS 80 lathe with SX-74 cutter head up and running. Not in time to cut the Rage LP (it was done at Masterdisk), but in time for Pearl Jam's new double LP. Ludwig was tired of losing the growing LP-mastering business, so he's back cutting lacquers. He also told me that, from what he's seeing, digital recording and/or mixing in the rock world is "dead." Virtually everything's coming in on two-track analog. In my vainer moments (most of them), I, ah, like to think I had something to do with this.

Mikey does camarillo

The way I figure it, we were three days away from not having a premier pressing facility in the United States. Three days away from not having 180-gram RTI pressings. No Classic, no DCC, no Analogue Productions, no Mosaic, none of it. (Mo-Fi rolls their own.)

This bit of info came from RTI owner Don MacInnis when I asked him to recount how he came to be in this nutty biz. MacInnis isn't an audiophile and doesn't really spin records at home. So how did he end up running America's premier pressing plant?

I found out during a three-day visit to RTI, where I also inspected Acous-Tech's new cutting facility, RTI's joint venture with Chad Kassem's Analogue Productions. I'd been invited there to watch veteran mastering engineer Stan Ricker cut the lacquers for Analogue Productions' forthcoming five-LP Miles Davis boxed set containing the trumpet giant's early quintet sessions for Prestige.

MacInnis told me that, back in 1983, he was living in Los Angeles, working in retail management for Sears. "Tired of working for a company that big, tired of living in L.A.," he moved to Camarillo, then a sleepy agricultural town, and, wanting to keep the income flowing, went to a temp agency looking for two or three days a week of gruntwork.

When he got home that day, there was a message on his answering machine from the agency instructing him to show up the next day at RTI, where he was put to work in shipping and receiving. At the time, RTI was pressing for Windham Hill and American Gramaphone—two "indie" companies interested in quality (at least when it came to sound). This was, after all, before CDs, when the majors still had their own LP pressing plants. CBS had a 100-press facility just up the road in Santa Maria. One hundred presses. Those were the days.

The real meat of RTI's business back then was syndicated radio programs. That's how Casey Kassem's American Top 40, King Biscuit Flour Hour, and the others were distributed: via LP. Some of those "live in concert" syndicated sets are now quite collectible; you regularly see them for sale in places like Goldmine.

Back then, RTI shipped radio shows around the world. Each week hundreds of lacquers would be cut, plated, and pressed for those shows—all within a few days. Keeping up with that load was a full-time job.

So how did MacInnis go from a three-day "shipping & receiving" temp gig to owning the company? "The place was a madhouse," he recalls; his three days kept getting extended because the guy he was replacing was out on a medical leave and not responding to treatment.

Bill Bower, RTI's owner at the time, quickly realized that MacInnis was operating way below his station. One day, after the shift, he pulled MacInnis into his office and asked him what he was doing there. After hearing the answer, Bower offered MacInnis a real job at RTI. From the mail room to upper management in one week: only in Holly—er, Camarillo.

Toward the end of the '80s, Bower, almost 60 and thinking of retiring, approached MacInnis with a buyout offer. Buying a record plant in the late '80s? Wouldn't that be like buying the hammer-and-sickle franchise in Russia after the collapse of communism? Actually, no—while the commercial record business was dead, the radio syndication thing was still going full force.

CD pressing plants didn't want anything to do with syndicated shows: They were running full tilt, manufacturing large runs of expensive commercial product, and had neither the time nor the inclination to do small runs on very tight deadlines. Syndicated radio shows and high-quality cassette duplication kept RTI going for years. Both markets are now gone.

Still, when MacInnis was approached with the buyout offer, RTI's sales were already only half of what they'd been a few years before. Though the future of vinyl looked bleak, MacInnis had a vision not shared by Bower; rather than forming a partnership that would have inevitably led to bickering, the two negotiated a five-year buyout.

MacInnis foresaw the resurgence of vinyl as an audiophile medium (RTI was already pressing for Reference and Sheffield): the key was high-quality, 180-gram LPs. Given the state of analog ca 1990, would you have bet the farm on its recovery? You gotta admire the guy's guts, especially given that he was getting married right around the same time. Imagine this scene in 1990: "Hey honey, here's our nest egg: a record-pressing plant!!!!"

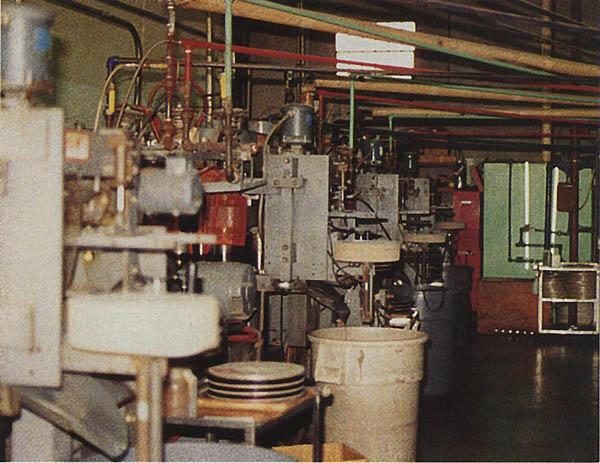

MacInnis bought a facility with six presses, only three of which were operating, and only a few days a week at that. Even before buying the plant, the daring entrepreneur had record-press expert and plant supervisor Rick Hashimoto working on the 180-gram concept: retooling, changing dies, and tinkering with the process took a full nine months of experimentation before the presses were turning out discs of consistently high quality.

RTI was pressing AudioQuest and Analogue Productions LPs at the time—the first trickle of the "vinyl resurgence''—and by 1991 MacInnis felt comfortable enough with the 180-gram process to offer it to the labels. AQ was first off the press, followed by AP. Within a few months, RTI needed two more presses to keep up with the demand.

A year and a half ago, RTI had five 180-gram presses going. Today it's down to three. Why? AudioQuest isn't pressing every title on vinyl, Reference has all but stopped, Classic's volume per title has dropped from first pressings of 6000 per title to about 3500. This is not necessarily bad news—the fact is, there are so many titles out there now, everyone can no longer buy everything. That's good.

What's not good is that not enough new vinyl enthusiasts are entering the market to pick up the demand. If we don't increase the size of the vinyl-buying population, and if those already in the market don't buy, the future will not be as pleasingly black as it is today.

Fortunately for MacInnis and RTI, as the 180-gram business began to taper off, the indie rock business picked up. Labels like Touch and Go and Drag City discovered what Sub Pop already knew: RTI pressed high-quality records. And make no mistake, these labels care about quality. There are superb-sounding records on all of these labels that would thrill adventurous audiophiles both musically and sonically.

For a while there was only one 180-gram press operating, but a huge backlog of orders for the indie market kept five 120-gram presses running. Today RTI is back up to three presses running 180-gram, with Analogue Productions, Classic, King, DCC, and Mosaic all having records pressed while I was visiting. DCC's project was a reorder of the spectacular-sounding two-LP Raiders of the Lost Ark set. At the same time, the indie scene is in a bit of a lull. In other words, the market is very volatile—and somewhat fragile.

Still, MacInnis is confident about the future of vinyl—so much so that RTI is installing a new external boiler (for heating the vinyl pellets) and a new, roof-mounted blower unit. These expensive investments will allow the presses to operate in a much cleaner and airconditioned environment, and there'll be room for another press where the old boiler once stood. Whether RTI will need another press is really up to you.

During my discussion with MacInnis we touched on many subjects, including what JVC did to its premier pressing facility in Japan, which once did contract work for King "Super Analog," Reference, and Mobile Fidelity, among others. JVC didn't just shut the plant down, it destroyed all of the presses, even though many companies—including Tam Henderson's Reference Recordings—tried to buy them.

MacInnis, through Henderson, offered to pay JVC to have its pressing-plant experts spend a few weeks at RTI to help them improve their quality. No go.

"Did you ever hear of a company willing to destroy its assets when buyers were available?" I asked MacInnis.

"No," he replied.

"Why would they do this?" I said. "I don't know, some kind of philosophy of 'We're done with this, it's not going to be of any use anymore.' ''

Equally frustrating, the guys who worked in the pressing plants, possessing all of this key knowledge MacInnis would like to tap into, and who would like to help, seem to be forbidden by JVC from doing so. Sinister, if you ask me. To this day, no one outside of JVC is privy to JVC's SuperVinyl formula, arguably the quietest, finest-sounding vinyl ever made.

It would be no skin off JVC's nose to give or sell the formula to RTI, along with the requisite knowledge needed for handling it in the presses. But no-o-o-o-o!! Guess which company's consumer electronics products I avoid?

Adding links to the chain

Up until recently, while RTI had a small plating facility, the really top-quality work was being done at Greg Lee by the late, great Ed Tobin. MacInnis watched the volume of plating increase to the point where he felt he was losing too much business by not offering a premier plating facility to go with his top-shelf pressings, so he upgraded his equipment, adding the crucial pre-plating step necessary for the creation of the high-quality "mothers" and stampers required for audiophile vinyl.

With the upgraded plating facility operating, the only link missing at RTI was a cutting lathe. MacInnis wasn't about to move in that direction by himself; however, encouraged by Acoustic Sound's Chad Kassem, he began to explore the possibilities. Kassem had been giving his mastering work to Doug Sax and it was costing him a bundle; plus, Sax was busy mastering so many commercial CD projects, Kassem's tapes ended up sitting on the shelf.

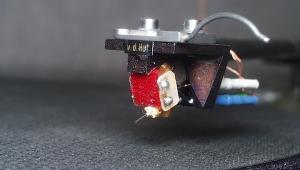

A perfect lathe room already existed at RTI: acoustically isolated and treated, it had been used as part of the old tape-duplication service, and had sat empty for years. When Wilson Audio Specialties decided to get out of the record business, Dave Wilson offered Kassem and MacInnis his lathe (driven by an Audio Research tube amp) and associated equipment. They bought it and went into business together as Acous-Tech Mastering. (ATM is a totally separate entity from either RTI or Acoustic Sounds. When Analogue Productions—Kassem's label—uses the facility, it pays like any other client.)

The new company hired veteran mastering engineer Stan Ricker, who, ironically, had been chief mastering engineer at the old JVC Cutting Center in Los Angeles, and later cut for Mobile Fidelity. The attractiveness of a "one-stop" cutting, plating, and mastering facility has proven to be a strong lure. Right out of the box, business has been strong—there's been more outside work (including, in another irony, for Japanese record companies) than work for Kassem's own Analogue Productions.

Not that Kassem hasn't been busy using his new lathe: Since setting up the facility he's issued Junior Wells's essential Hoodoo Man Blues (Analogue Productions APB 034), a Stereophile "R2D4" in its Delmark CD incarnation. It's also the first of AP's "Revival Series" of $17.98 LPs—an eclectic bunch of records including Otis Spann's Good Morning Mr. Blues (AAPR 3016), and Sonny Boy Williamson's Portrait of a Blues Man (APR 3017), culled from the same session that yielded the legendary Keep It to Ourselves, originally on Alligator and another R2D4. I'm not going to run down the entire series here except to say that it's worth exploring both for the music and the sound.

During my time at RTI I also interviewed Chad Kassem and Stan Ricker. Kassem's rise to preeminence in the analog audiophile world is even more unlikely than MacInnis's. It's a story worth telling and I plan to do so in this space soon. As for Ricker, he's a legend. His analog tales, from the early days on, will also make for some memorable reading. But since what we've got here is not a book but a magazine column, that, too. will have to wait for a future installment.

Cool tools two

Last time, I brought some analog aids to your attention. Here are a few more.

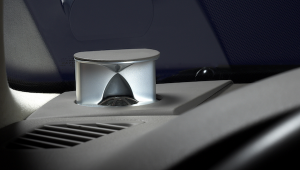

How tight is "tight''? Ever ponder that question when torquing down a cartridge in a headshell? I have. Well, Rega has the answer: a really neat cartridge torque wrench in the form of a precision-made, round-knurled metal cylinder a bit smaller than a 35mm film canister. Protruding from one end is an Allen wrench that fits the hardware supplied with most of today's high-quality cartridges.

You stick the end into the screw head and turn...and turn...and turn until you think the damn thing's gonna snap the head off—and suddenly there's a click as the wrench reaches its preset maximum. Four clicks and you're there—probably much tighter than you would have suspected it would be safe to be. But it is.

Rega's torque wrench costs $125. Not for everyone, but certainly for serious analog addicts and professional installers. (Imported by Lauerman Audio Imports, 108 Jackson Ave., Knoxville, TN 37915. Tel: Tel: (423) 521-6464. Fax: (423) 521-9494.)

The old standby record-cleaning brush—the Hunt EDA, a carbon-fiber/felt-pad combo imported by Roy Hall of Music Hall—has a new challenger: the CA 2+2 record brush. (Imported by Pro Audio Ltd., 111 South Drive, Barrington, IL 60010. Tel: Tel: (310) 394-4488.) The 2+2 uses two sets each of two types of brushes—carbon fiber and "aromatic polyamide''—cut in two lengths of bristle. Hence the name. (I don't know why they call the stuff "aromatic polyamide'': I put it up to my hooter and didn't smell a thing. [The world of organic chemistry—the chemistry of carbon compounds—is divided into "aromatic" and "aliphatic" compounds, those with and without benzene rings, respectively.—Ed].)

One set of bristles is on the flip side of the insert. To access them, slide the brush assembly out of the holder, turn it upside down, and reinsert it in the holder. The second set of bristles is shorter, which makes them somewhat stiffer, and thus more effective on dustier records.

I know the founder of this publication does not like record-cleaning brushes, but I beg to differ. No, these devices should never be used as cleaning devices. The only way to clean a record thoroughly is with a vacuum-operated cleaning machine—an essential tool in the war against analog dirt. If you try using a carbon- or "aromatic''-fiber brush or Discwasher to clean a record, you'll only smear the filth around while contaminating your cleaning device. In fact, if you use a vacuum machine on a really dirty record without first using cotton wads and an Orbitrac to remove the real filth and grime, you'll do the same thing.

But when used in a conscientiously applied program of regular vinyl hygiene, these brushes do serve a purpose: they're very useful for manicuring loose, dry dust from already cleaned records. I recommend giving even the cleanest record in your collection a once-over with either the Hunt or the 2+2 before play. Believe me, while you were playing your pristine LP that last time, the three Ds—dust, dandruff, and detritus—were falling on it. Just don't press down on the brush as you rotate the record—let the brushes, not pressure, do the work.

Finally, some REAL trouble

One of the neat things about having a monthly column is that you can write about things not deserving of a full review but worthy of mention. One such thing is the unmentionable "magic clock" I'm sure you've heard of and dismissed—unless you have one.

Laugh all you want. I'll laugh with you because the concept is laughable and the product is ho-ho-ho—until you plug it in. I'm not the only reviewer who swears he hears the benefits: A few manufacturers feel likewise, including a very-well-known and well-respected electronics designer who at one point considered—in fact, did ship his products to the Coherent Systems Corporation (inventor, discoverer, whatever, of whatever it is) for "processing."

Ditto a line-conditioner manufacturer who flew to California to try to learn the "secret" of the process and arrange to become the manufacturer and distributor of the product. Rebuffed, he began doing his own thing in this area of arcane electricity.

So what are we talking about here? The product is the Electraclear EAU-1—a small black box you plug into the wall, in the same set of sockets as your stereo system. (Though I'm not suggesting that the products are at all similar in design, there is a precedent for this in MIT's Z Stabilizer, designed by Richard Marsh—no mystic he.)

Claims made for plugging in the EAU-1 include: "increased timbral clarity, higher resolution and cleaner sound, added depth, presence and fullness, greater definition and distinction, reduced harshness, neutralized AC interference, reduced signal indecision, greater involvement."

I hear everything claimed when I switch the damned thing on, but don't ask me what "reduced signal indecision" means.

I love this: you are warned "DO NOT OPEN: RISK OF ELECTRICAL SHOCK" on the back of the box, but the company surely knows that everyone will open the box: When you do, a sticker inside reads: "This simple circuitry provides a vehicle for Coherence Technology. This invisible coherent, conductive electromagnetic field effect technology neutralizes electron 'noise' or interference and the harmful effects of electromagnetic radiation."

Don't ask me what that means either, or how it does what it claims to do, or why you should have to pay $400 for a box, a circuit board containing a few parts and one IC that doesn't even look like it's in the circuit, an IEC AC jack, an on/off switch, and a neon light—all of which can't cost more than $50 bucks to manufacture. But then, "value" has never been a hallmark of audiophile equipment—especially accessories.

The claims made for this product in the accompanying literature are surpassed only by what's in the Chinese manufacturer's brochure. Among other things, they claim that their speakers will make your hair grow better.

An excerpt from the Coherent Music Systems literature: "When the inaudible noise or interference is eliminated, you will notice the absence of the inherent stress and fatigue in electronic sound and images. Music and video feel more alive....

"Each of our bodies metabolizes our entire environment [in] 1/1000th of a second. When the electromagnetic fields in your environment contain stress and chaos, your physiology must process these harmful qualities. If the fields resonate with coherence and consonance, then your physiology processes these beneficial qualities."

Clear enough, but how does it work? According to another part of the brochure, "The Electraclear features an advanced superconductive electromotive, coherent technology, UT Code;r, which utilizes complex principles of resonance to change the quality of electromagnetic fields surrounding all the equipment [to] assume a positive or balanced vortical energy flow." It goes on from there.

I don't know anything about the mumbo jumbo in the literature. Nor can I make sense of the graphs and charts that accompanied the unit (though that could be my problem). But based on these supporting documents, the whole thing sounds like a lot of horsehockey to me.

What I do know is that I was able to sit in my listening position with the thing plugged into the wall and on my lap. I could switch it on and off while listening to music. No, it wasn't "double blind" A/B/X, but I swear I heard less texture, more bloom—all of the things claimed in the literature. I felt more relaxed, as did the musical presentation.

Can I live without the EAU-1? Yeah. Will I? Yeah. Is something going on here, or is it the sort of difference gold and silver faceplates make to the sound of a preamp? I don't know. If you order an EAU-1 from Coherence Music Systems (943 Euclid St., Suite A, Santa Monica, CA 90403. Tel: (310) 394-4488.), you can try it out for two weeks and, if you hear nothing, return it for your money back. What have you got to lose except the time and energy it will take you to listen, then write and tell me if you hear what I hear?

- Log in or register to post comments