Companies mostly sell the products by its online marketing method that users purchased of online shopping and its reliable on your time.

Analog Corner #20

(Originally published in Stereophile, March 12th, 1997)

Lurkers on this printsite considering taking the analog plunge but concerned that all of the good used records have already been bought, leaving them to face a life of hideously expensive reissues—fear not! There are still billions and billions of great black biscuits out there, yours for a song—or a buck or two.

A few weeks ago, WFMU—one of New York City's better listener-supported radio stations—held its annual benefit "record convention" in an East Village church basement. Though it was a cold, rainy December Saturday, the crowd snaked around the block hours before the 10am opening, each attendee happy to pay the $10 early-entrance fee. Later arrivals paid just $4 for the privilege of picking through tens of thousands of records hauled there by seasoned dealers and novices alike.

Who were these vinyl fanatics? Not the middle-aged, food-stamp–eligible misanthropes the music biz would like to think are the only buyers left for the cumbersome old technology. The hundreds of folks I stood behind (damn them!) were mostly young, intelligent, upscale, and, of course, decidedly geeky—no different from the COMDEX crowd, actually, though I doubt these folks' idea of fun is "surfing" the Net—not when there's vinyl to spin!

Calling browsing the Internet "surfing" is like calling reading the encyclopedia "skiing." Except that with encyclopedias, when you turn the page, it's there! You don't have to wait five minutes before it "rezzes up." The Internet: truly one of the greatest single mass deceptions since the invention of the Compact Disc—or the election of Ronald Reagan (take your choice). But that's all you hear about. Every newspaper has an Internet column. The Chicago Tribune has dropped Rich Warren's longstanding audio/video column in favor of "software, video games, and other computer-oriented topics. (Footnote 1) "The "Web" even has its own cable station—MSNBC.

It's pathetic that computer nebishes like Bill Gates have managed to convince the general public that sitting on one's arse and waiting 10 minutes for some stupid digitized photograph to assemble is "cool." Silicon Valley aims to take over music delivery and television, too—and if you don't think so, you haven't been following the wrangling over HDTV standards. These guys want to replace today's "mini-systems" with tomorrow's "mini-musicomputers," which will go online, download music, and play it back for you. Sound quality? Who cares? Think of the convenience! Think of the numbers crunched!

Meanwhile, in the public's eye, what you listen to is the equivalent of your Uncle Herman's Sears console. Your hobby is up there with shuffleboard. Get the picture? It could have happened to Rolex too, after quartz watches were invented, but it didn't. My message to the "high-end community" is $Bwake up and smell the rosin core!!!

Sorry. Where was I? Oh yes—on line (on a real line) in the rain with a bunch of foulbreathed vinyl dweebs. When the doors opened, the crowd stampeded in and the frenzy commenced. I steered clear of the seasoned dealers with their expensive, alphabetized, plastic-covered treasures, and instead sought out the disorganized schleppos eager to dump their "obsolete" record collections on unsuspecting fools who hadn't yet read the news: The digital revolution is being televised!

First I found a guy from Philly trying to sell his late Uncle Harold's record collection, which he'd inherited. Uncle Harold sure had a lot of schmutz—101 Strings, Jerry Vale, and the like—but he also had a few Living Stereos, including "shaded dogs" of the Reiner/Heifetz Brahms Violin Concerto (LSC-1903) and the wonderful Fiedler/Wild Rhapsody in Blue/An American in Paris (LSC-2367). Harold had obviously had little use for these (they were basically unplayed); I picked 'em up for four bucks a piece. Good start.

Then I bumped into a chunky, bearded biker type who just wanted to unload a few boxes of records fast—any two for five bucks. What did he have to dump? How about virtually the entire British Virgin XTC catalog at two for $5—unplayed! I got Drums and Wires, Black Sea, Mummer, and the spectacular-sounding English Settlement—which, though two discs, was still just $2.50. As was a very clean British original London Calling—forget the American Epic pressing. I also got the original Paris Blues soundtrack album, by Duke Ellington with Louis Armstrong, on an original United Artists pressing; and an original, German-pressed, spectacular-sounding Who's Greatest Hits, a mint second British pressing of The Beatles' "White Album," and some other gems too. So don't tell me the great records are all gone.

I ran into Stereophile's Rick Rosen, who'd taken the opposite tack and found some records on his longtime wish list for which he was willing to drop some serious shekels, including a Sun Ra disc, and an Eric Dolphy on Prestige that I obnoxiously said I'd seen "a million times." Actually, I had—it had been in the bins of a Harvard Square record store I'd worked in back in 1969. Oy! To have what was in those bins now! Still, it was obnoxious of me...but what else is new?

The next weekend I went to a garage sale that listed "records." By the time I got there, the RCA collectors were coming up the stairs with a few minor titles. "Nothing there, Fremer." Oh yeah? I came away with a mint original British Island pressing of ELP's awful version of Pictures at an Exhibition—but what sound! And an ultra-rare mint mono pressing of Buffalo Springfield's first album, without "For What It's Worth," listed in the Goldmine guide at $100; and the J. Geils Band's first LP; and Steven Stills's first solo, on an "1841 Broadway" pressing; and a really clean original Joni Mitchell Blue with the blue insert. You haven't heard Blue until you've heard an original pressing (it has the word "$Bstereo" at the bottom of the label instead of the "W" Warners logo). Those later pressings are pale imitations. For the most part with Warner/Reprise discs, the later the pressing, the paler the sound.

I also got an early second pressing of The Kinks' Village Green Preservation Society; an original Verve Oscar Peterson and Nelson Riddle; a Savoy original Opus de Jazz with Milt Jackson, Frank Wess, Kenny Clarke, Hank Jones, and Eddie Jones; an original green-label early Columbia pressing of The Louis Armstrong Story; and, for good measure, a 10" Sidney Bechet Blue Note, plus a very clean "shaded dog" of Franck's Symphony in D Minor with Monteux/CSO—my favorite performance, even though Lewis Layton overloaded the tape in a few places. A buck each.

The lesson is clear: There are still great records to be had for cheap, if you're willing to bend over for them. Or you can bend over and let the record industry have at you for 12 bucks a pop on CD.

Cleanup time!

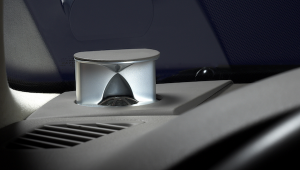

A natural segue, of course. I wish I could give you a hands-on account of the new Orbitrac, but for some reason Allsop forgot to send me one—it'll have to wait until the next column. Meanwhile, I recently received a call from H. Duane Goldman, aka The Disc Doctor, manufacturer of The Disc Doctor's Miracle Record Cleaner and Miracle Record Cleaning Brush.

Unlike some who ply the grooves with fluids and the like, Goldman would seem to be actually qualified to do so—he holds a Ph.D. in chemistry. The good doctor sent me a small bottle of his heavy-duty, nonisopropyl alcoholic fluid and a pair of nifty cleaning brushes to try out—which I did on some of my more recent catches. I also tried cleaning a few discs I'd already cleaned using the methodology I'd adopted from Michael Wayne's article published in issue Four of the The Tracking Angle. Fortunately for my sanity, the two products are not dissimilar. In fact, they're quite compatible.

Disc Doctor manufactures products and provides cleaning regimens for both modern vinyl formulations and older shellacs, acetates, and Edison Diamond discs. There's also The Disc Doctor's Miracle CD Cleaner, but I'll leave that to Bob Harley. The miracle there, of course, would be if the fluid could somehow make listening to CDs enjoyable.

The Disc Doctor's Miracle Record Cleaner contains no isopropyl alcohol—Goldman says it extracts from vinyl the fillers and extenders used to increase the elasticity of most record formulations. The last thing you want to do is drag a stylus through brittle vinyl! At the same time, his research demonstrated that alcohol-free solutions were incapable of removing mold-release compounds, so his final formulation contains a very low concentration of the water-soluble alcohol, 1-hydroxypropane (n-propanol).

The rest of the fluid is purified water and a number of "modern surfactants" (don't want to use those outdated surfactants!): sodium ethylenediaminetetraacetate, ammonium dimethylbenzenesulfonate, and triethanolammonium dodecylbenzenesulfonate. What a mouthful. Speaking of which, you don't want to swallow this stuff—keep it out of the reach of children and pets. Suffice it to say, if you want to mix up your own, you probably can't find these ingredients at your local WalMart. (Though you can find there the latest in censored CDs!)

And why would you want to make your own fluid when The Disc Doctor's Miracle Record Cleaner is so ridiculously inexpensive? A pint will clean 300–350 records and costs just $17.95 plus $4.75 postage. (Unfortunately, you have to pay to ship water, and water is heavy.) Or you can buy a quart, enough to clean 600–700 records, for $28.95 plus $7.25 postage. Or, if you want to invest in cleaning-fluid futures (Goldman claims it has infinite shelf life), you can buy a gallon for $59.95 plus $14.50 postage, and clean 3000 records.

The fluid comes "extra strength." Even for cleaning the usual garage-sale suspects, Goldman recommends diluting the stuff—two parts cleaner to one part distilled water. My advice? Make sure the "distilled" water you use has been steam-distilled, as opposed to having been passed through a chemical resin. So diluted, Miracle Record Cleaner is said to remove dirt, grime, grease, mold, and mildew, and, at the same time, to reduce static charge and rinse residue free. What more could you want from a record-cleaning fluid? Plus, it slices, dices, chops, grinds, peels, gives your children great haircuts, and has a built-in fishing rod that fits into your pocket!

But the fluid is only part of the story. Goldman—who, in our various conversations, struck me as being mildly obsessive/compulsive (a good thing if you're going to be in the record-cleaning fluid business and dealing daily with analog lovers, who are, by definition, themselves obsessive/compulsive—has spent a great deal of time perfecting his cleaning brushes.

For one thing, the handles aren't made of wood. Ever have a VPI brush slip out of your hand and divebomb a record you're preparing to vacuum? Ever watch VPI's hard clamp play field hockey on a treasured piece of PVC? I have.

The Disc Doctor's brush sort of looks and feels like a large licorice I-beam. It's easy to grip, pliable yet firm, and has a wide surface area wrapped with a replaceable black plush polyester-and-nylon pad. This brush makes record cleaning almost pleasurable. You use one brush to apply the fluid, another to apply distilled water.

Once you've diluted the fluid, you apply about a fifth of a teaspoon to a dampened pad. Then, with the record on a flat surface, you brush back and forth, following the grooves, over about a third of the record. Repeat on the other two thirds and you're ready to remove the fluid—but not with your cleaning machine.

Goldman recommends sopping up the fluid with a 7" cotton square. Here's where the Orbitrac really comes in handy. Once you've removed the fluid, you take a second brush saturated with distilled water and work that into the grooves. Goldman's instructions then tell you to sop up the distilled water with another cotton square, repeat on the other side, then allow the record to "air-dry." Better believe that's where I use the vacuum machine! But if you don't have a vacuum machine, change pads (on the new Orbitrac), or use a second Orbitrac and dry the record with that.

I also follow that with a dose of Torumat-7XH fluid followed by another vacuuming. Why? Because I have a gallon of it and I like to finish off the process with something other than water—don't ask me why. (Mr. Goldman doesn't agree.)

The combination of The Disc Doctor's brushes and fluid, a gallon bottle of distilled water, an Orbitrac, the Torumat-7XH, and a VPI 16.5 does an outstanding job of cleaning records. Does it do a better job than what I used to do? It's almost the same regimen, and that was really effective, so I can't say for sure—and if you think I was going to take two records and do A/B comparisons, forget it! Life is too short. There's too much music to play.

I can tell you that, when used as directed—that is, with the pads and the final distilled-water douche—the cleanup never left a residue on the record, and never clogged the stylus. It did, however, leave sparkling-looking, pristine, quiet surfaces.

I love the feel of the Disc Doctor brushes, their effectiveness, and the overall added convenience they bring to the cleaning process. An LP-sized pair and two replacement pads is a very reasonable $22.95. Less-expensive brushes for 45rpm and 10" LPs are also available.

My only complaint is the less-than-detailed, less-than-meticulous cleaning instructions Disc Doctor provided with the brushes and fluid. You're told to apply the fluid with a "dampened" brush. Dampened with what? Distilled water? Cleaning fluid? Soy sauce? Doesn't say.

Once you've cleaned a side, you're instructed to "dry the work surface," turn the record over, and do the other side. But I wouldn't put the clean side down on the same surface that had just contacted the dirty second side—I'd use a different surface for each side. Corkboard—like the stuff VPI uses for its cleaning-machine platter—makes an ideal work surface.

You're advised to "remove dirty rinse water from the WET BRUSH by running your finger down the length of the fabric." I wouldn't do that either. I'd use a rubber squeegee or a clean nylon nail brush. Skin is oily.

Okay—picky, picky. Goldman told me he's rewriting the instructions to make them clearer and more user-friendly. One thing I like about Disc Doctor fluid is that the ingredients are listed on the bottle—no guessing, no hocus pocus. If you're worried about sodium ethylenediaminetetraacetate, ammonium dimethylbenzenesulfonate, and triethanolammonium dodecylbenzenesulfonate kissing your vinyl, you can try something else.

I think if you try The Disc Doctor's Miracle Record Cleaning system—the fluid and the brushes—it will become at least part of your cleaning system of choice. It is part of mine, along with the Orbitrac, the VPI 16.5, and the rest. If vacuum-assisted "record cleaning" for you is applying fluid, brushing with the VPI bristle brush, and vacuuming, you're not really cleaning your records. What you're doing is smearing goop on the VPI velvet lips and spreading the "wealth" to all of your other records.

Contact Lagniappe Chemicals Ltd., P.O. Box 37066, St. Louis, MO 63141. Voice/fax/modem: (314) 205-1388. E-mail: lanyapinlink.com , or (gasp!) check out their Web site: http://www.prlink.com/discdoc.html .

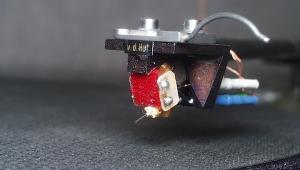

Put a load on your cartridge

When I got the FM Acoustics 122 phono equalizer for review (see elsewhere in this issue), I was confronted with designer Manuel Huber's insistence that all moving-coil cartridges require resistive loading down, even if the manufacturer specifies 47k ohms. Up to that point I'd run all MC cartridges at 47k, as most audiophiles do, and as most cartridge importers and manufacturers instruct.

Huber's point is that a cartridge is a motor, and a motor resonates and needs to be controlled. If loading makes a cartridge sound sluggish and distant, he insists, it's not because the load is wrong, but because the electronics weren't properly designed.

Loading down the Transfiguration Temper, the Lyra Clavis D.C., and the AudioQuest Fe5 with 100 ohm resistors vastly improved the performances of all three cartridges. Focus, control, and overall presentation became more lifelike, less "hi-fi''–ish. Image edges lost their artificial "crispiness" and sounded more natural. At the same time, images became more solid and less ethereal. I came to find that what I had taken to be "air" and "extension" were lack of control and motor resonances. Yes, it did take adjustments of both attitude and ear to get used to the sound, but it's like jumping into a warm shower (which at first feels cold): Once you acclimate, you won't want to go back.

Much to the consternation of Audible Illusions designer Art Ferris, I loaded down the 3A's gold phono boards with 100 ohm resistors—the improvements in overall clarity, bass control, and image definition were significant. I had equally good results with the Audio Research PH3.

Part of the resistance to "loading down" is the term itself. It sounds as if you're burdening the cartridge with a heavy weight. Don't think of it that way! Try it using high-quality, close-tolerance resistors, and—unless your system already sounds slow and sluggish—I think you'll find that your system will sound less "hi-fi''–ish and more natural. Try it and tell me what you hear.

Primyl Vinyl Exchange

Bruce Kinch edits and publishes Primyl Vinyl Exchange, a bimonthly vinyl-oriented newsletter (Footnote 2)—your basic black-and-white, single-staple job—containing articles on record-cleaning, care, preservation, collecting, and so on.$s2 While PVX is very short on musical insight, it does offer some good (though frequently less than complete) advice on the sonic values of different pressings, reissues, and the like. It also offers some interesting DIY projects, like tips on making a homemade vacuum cleaning machine, and making your own record-cleaning fluid (December 1996)—something I now wouldn't do, given the Disc Doctor's reasonably priced fluid. And because as a venue it's inexpensive enough that many smaller record dealers can afford to advertise in its pages, PVX is quite valuable as a resource for finding good used "audiophile" records.

PVX's fetishizing of Harry Pearson's "Superdisc" list in The Abso!ute Sound is a bit much, though. Mindlessly collecting someone else's tastes in music is silly and obsessive, in my opinion. Almost all of HP's choices sound good (I've mindlessly collected much of it), but his classical tastes are rather specific (heavy on contemporary British composers), and anyone who in 1982 would call The Sheffield Track Record "Absolutely the best-sounding rock record ever made," and who thinks the group Rough Trade is it, or who thinks David Crosby's If I Could Only Remember My Name.... has musical value (Footnote 3), should be followed at a safe distance when it comes to pop music! Do yourself a favor and mindlessly follow me.

Fer instance: The German Speakers Corner label recently issued two superb-sounding and musically nourishing LPs. One is an original Archiv Produktion (a division of DG) called The High Renaissance: dance music from the 1600s by Michael Praetorius, Erasmus Widmann, and Johann Hermann Schein. Donna Summer it's not, but it is some of the most tuneful and delightful music you'll ever hear, whatever your taste. And the sound—the bells, harpsichords, glockenspiels, strings, and the buzzing rackett—is superb. The original (Archiv ARC 73153/198 653 SAPM) is on HP's "Superdisc" list, though I've owned it since before I ever read an issue of The Abso!ute Sound. The reissue's catalog number, 198 166 SAPM, is different from my original, perhaps because it is the German-language original cover and title (Tanzmusik der Praetorius-Zeit), whereas mine is in English. If you've ever heard The Fifth Estate's "rock" version of "Ding Dong the Witch is Dead," you'll hear where they got their bridge.

Another outstanding Speakers Corner reissue (which I'm sure WP will fill you in about in "Quarter Notes'') is Smokin' at the Half Note, an original Verve issue (V6-8633) featuring Wynton Kelly with the Kind of Blue rhythm section of Jimmy Cobb and Paul Chambers, plus Wes Montgomery on guitar. Wow!!! Best recording of Wes's guitar I've ever heard.

One last LP tip: The German ARS (Audiophile Record Service) label has issued a killer LP version of Santana's Abraxas ("Black Magic Woman," etc.), available from Media Access, (715) 698-3254.

Yikes! I'm out of space. We'll have the fascinating interview with Stan Ricker next time.

Footnote 1: According to a November '96 letter from the Tribune's Deputy Managing Editor, Gerould W. Kern, to Brian Walsh, President of the Chicago Audio Society.

Footnote 2: For subscription information (six issues/$15), contact Primyl Vinyl Exchange, P.O. Box 67109, Chestnut Hill, MA 02167. Tel/fax: (617) 739-3856.

Footnote 3: Ahem. This David Crosby album is one of Michael's current editor's all-time favorites.—JA

- Log in or register to post comments