Thanks for an informative review. Do you know if the vinyl release of Bitches Brew on Sony Legacy is taken from the original analog tapes or is it another CD/digital transfer?

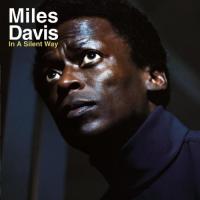

Columbia/Legacy Reissues Miles's Transitional Masterpiece on 180 Gram Vinyl

Maybe the soundtrack to your life didn’t exist in 1969, or if you’re fortyish, was filtered through an amniotic sack.

1969 was an unsettling year. The fall was post-Woodstock and spelled the end of the ‘60s, though what we now think of as “the ‘60’s” arguably didn’t happen until the ‘70s.

Vietnam and the draft were in full-swing. Nixon was president. Nixon ! I’d moved to Boston to attend B.U. law school. Law school? Yes. Boston was a town in the midst of decay. The WWII generation had reached middle-age and moved to the suburbs leaving the frail, the elderly and the college kids.

I moved into a basement apartment in a private home in Brookline on the street where John F. Kennedy was born. There was a commemorative plaque. He’d been dead but six years and the trauma was still fresh. I relived the event every day passing the house.

I was in high school gym class when I heard. Mr. Rhodes announced “The President and the Vice-President have been shot…” “Hypothetical,” was my first thought," and they want to see our reaction, but why in gym class?” “So get dressed and go home.”

The woman who owned the home on that Brookline street needed the extra income to take care of her husband who was bedridden with emphysema and needed an oxygen tank to breath. A pair of eccentric elderly spinsters out of a Hitchcock movie lived directly above and whenever I played the music too loud, which was always, they’d bang on the floor with a cane.

It was a weird, unsettling time. The veneer of wealth in Boston was spread thin. There was the old money of Beacon Hill and the new of the Prudential Center on Boylston Street, behind which was the Christian Science Center. But a block behind that was a literal desolation row—block upon block of abandoned, haunted housing—a sprawling ghost of a neighborhood that looked as if an entire population simply up and left en masse, which is pretty close to what had happened when the suburbs grew after WWII.

On the other side of town where Storrow Drive wound by the Hatch Shell and elbowed its way on ugly green girders towards the once vibrant waterfront, slicing it in half (since remedied by "The Big Dig"), another such abandoned neighborhood had been replaced via “urban renewal” with some godawful looking apartment buildings. “If you lived in Charles River Park” the sign beckoned the newly suburbanized commuters, “you’d be home already.” Yecch! I wondered which was worse: these ugly slabs or the abandoned neighborhood behind the Christian Science Center?

I got through my first year of law school and almost made law review. I fed my vinyl habit working at Minuteman Records in Harvard Square and attended as many concerts as I could at The Boston Tea Party on Lansdowne Street. I saw The Kinks, The Who and I can’t remember who else along with a few hundred others into the “underground” rock scene. The Kinks were never big and The Who didn’t break big until Tommy, which had been released the year before and took some time to catch on.

That first Boston summer after school had let out, I picked up a kid hitchhiking on Commonwealth Avenue. Hitching was commonplace back then and I actually made some good friends that way. I also got kidnapped and forced to drive some heroin addicts to Maine, but that’s another story!

Anyway, this kid put out a big green Styrofoam thumb and I stopped. He ended up being my roommate the next year along with an old college buddy.

We got an apartment on Commonwealth Avenue just in time for the MTA to begin replacing the antiquated, bulbous-looking orange and tan trolley system that more closely resembled “The Toonerville Trolley” than something you’d expect to see in a modern city. But then again, Boston 1969 was anything but modern.

Replacing the trains required replacing the tracks so for an entire year, the soundtrack to my life was constant jackhammers and In A Silent Way introduced to this rocker by my hitchhiker roommate. A summer with this cat introduced me to a whole lot more than this Miles album. By fall I found myself taking a semester's leave of absence from law school.

In fairness to my friend who shall remain nameless (he’s now a world renowned Go-Kart racer, believe it or not), by then I’d also begun producing and voicing radio commercials for the record store in which I worked and the funny spots quickly became popular in Boston and I’d become a minor “cult” item both on the underground station WBCN and among listeners at the Top 40 station WRKO.

This was a train I was happy to latch onto as an excuse to get the hell away from law school. So, for the entire year in that apartment, we listened to, among other albums, In A Silent Way, Miles’s mysterious, dazzling descent into electronic cool. Yes there were other albums, mostly rock and many of them great too, but the one that defined the rapidly shifting period of time was In A Silent Way.

While the 19 minute first side is called “Shhh/Peaceful,” that year was anything but, either politically or personally. I never found the music peaceful either. To me it’s mysterious, unsettling and creepy, with a decidedly neon vibe.

If Kind of Blue was the cool, modal music for the “now” hipsters of the late 1950’s —the album that liberated adventurous listeners from a reliance upon chord changes— led by the electronic keyboards of Joe Zawinul, Chick Corea and Herbie Hancock and John McLaughlin's spider-webby guitar, In a Silent Way, was the shimmering, serpentine opening to a dangerous musical world. It was the soft sell that made possible the beautiful grotesqueness of Bitches Brew.

For me In a Silent Way was the insistent temptress that led me from middle class conventionality to life experiences unimagined just a few short years earlier. Led is the wrong word. Perhaps “enabled” would be better. The music was more of a lubricant than anything and with its often insistent rhythmic drive, the album became a favorite of an adventurous Rock generation, much as Miles himself had been influenced by the pop scene unfolding all around him.

In A Silent Way is all about atmospherics. Despite the high level of hiss, the murkiness and the less than stellar dynamics, I’ve always regarded this as a great recording because of its appropriateness to the subject matter.

Aesthetically, it’s perfection. Never mind that Tony Williams’s distant drums are shunted off to the right channel or that Dave Holland’s bass lacks extension and ultimate definition. All has been miked and placed for appropriate impact, with the ghostly keyboard apparitions dancing between and around Miles’ spotlit trumpet and John McLaughlin's warm guitar lines gliding along the left channel.

This 180g reissue marks a packaging improvement for Sony/BMG, compared to the flimsy, cheap jackets found on the label’s first series of vinyl reissues. Rainbo’s pressing quality continues to improve, though these are commercial, not audiophile quality pressings. Overall though, I have no complaints about noise or the physical fit’n’finish of this release. In fact, it’s much better than what Columbia was doing in the late ‘60s in terms of vinyl quality.

The sonics are something else though. Lacquer cutting was by Ray Janos at Sterling and I doubt an analog tape was the source, though I know that a recently installed preview head now allows Sterling to cut AAA. Nor was a high resolution digital file used. The first giveaway is the slightly dark timbre of the cymbals. More significant though, are the flatness of the drums, the lack of "woodiness" to the rim shots, the lack of air around Miles’s trumpet and its lack of imaging precision compared to the original LP as well as the two-dimensionality of the soundstage and especially the truncation of decay.

Still, if you don’t have a "360 Sound" original and can’t find one, there’s nothing “digital” sounding about this reissue in the pejorative sense of the word, so chances are you’re not likely to know the difference. It’s neither bright nor hard. It’s just missing atmospherics and the musical flow is on the sluggish side.

I’m guessing the source but I’d be willing to make a stiff wager it’s from a “redbook” CD file sourced from Mark Wilder’s excellent CD mastering for The Complete In A Silent Way Sessions.

Given that there is an analog tape that’s probably not all that difficult to grab from Iron Mountain, there’s something less than honest (actually cynical) about reissuing a classic album like this from a CD resolution file, if in fact, that’s what was used.

This isn’t bad, but Sony/BMG can do much better. Please, Sony/BMG, this isn’t an analog “game.” Vinyl buyers are serious: they want an all analog product, not analog veneer.

As for the music, forty years later it's all substance, no veneer and definitely worth owning and playing often.

- Log in or register to post comments