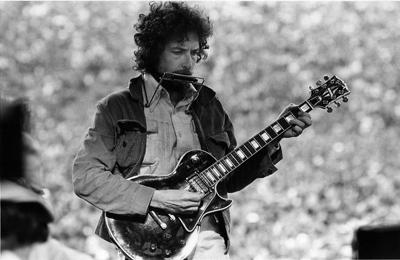

Dylan Then & Dylan Now. Forty Years Is A Long, Long Time...Or Is It, Really? (Part 2)

The second CD of the set, especially, functions as a kind of artist’s notebook, providing us discarded and unfinished versions of now-classic recordings from the pre-motorcycle-crash trilogy. From “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues” (track five) through “Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again” (track nine), we are offered works-in-progressa glance inside the artist’s creative processwith rhythmic variations, language refinements, and even wholly discarded or completely revised lines present in the working versions of songs that have become part of the canon.

Listening through these major compositions on the way to becoming, two things are most evident: the

Sometimes the change is more profound, as the passive image “fisherman hold flowers” from “Desolation Row” becomes “fisherman throw flowers.” Other times the changes are entirely wholesale, even when they’re dialed back, as in the switching of “they’re spoon-feeding Casanova the boiled guts of birds” for the more-demure “they’re spoon-feeding Casanova to get him to feel more assured....”

My personal favorite are the last three verses of “Stuck Inside of Mobile,” where the author-performer mumbles and stumbles his way through lyrics not only unfinished but more likely unimagined as yet.

In any case, the effect of giving us this private factory tour is not unlike the effect of a wizened, time-worn Dylan serving as narrator of the “No Direction Home” documentary. It’s the same effect we get from the replication of Dylan’s inner voice in “Chronicles, Volume One” he’s the crafty, old veteran now, no longer capable of brushing back hitters with his high heat or snapping off those crisp, nose-diving curve balls, but he’s got control, deep knowledge of the game, and a sharply observant insider’s view of his craft.

The truth is, I’d like as much as anyone to jump up on the Dylan Redux bandwagon, proclaiming the late-life return of an American geniusa Sixties icon for the iPod generation, as it werebut I’m not convinced the trio of post-modern studio recordings so readily embraced by today’s gaggle of critic/promoters really stands up to its pre-crash predecessor.

It’s a little too early in the historical process really to grasp the significance of Time Out of Mind, “Love and Theft”, and Modern Times compared to the established influence of Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited, and Blonde on Blonde.

For one thing, Modern Times is not an easy album to love, and one of the qualities that makes it so challenging is its density. The swing-beat/bluesy musical ambiance (embodying what Dylan describes as a “cowboy band”) and the gravelly crooning voice out front set one kind of aesthetic mood (seductive enough for a Victoria’s Secret ad), while the lyrics clip-clop along beneath, evoking images and intellectual attitudes that don’t always connect with the musical setting.

Not that Dylan’s ever written any differently. It’s one of the things that makes it so hard to think about him as a writer of love songsone of his main interests in relationships (or maybe obsession) tends to be the shades of ambivalence they evoke. For Heart of Mine…, Muldaur chose mainly the most tender-hearted declarations of love; an entire box set, on the other hand, could be produced from Dylan’s wry, cutting, wary, and ironic love songs.

But questions of stylistic evolution aside, it’s clear the method behind both Blonde on Blonde and Modern Times is exactly the same: cryptic, inscrutable lyrics, forged from the juxtaposition of unlikely images and highly evocative connotations, set to music that is remarkably uniform in its synthesis of remade materials reflecting one or another pocket of overlooked American regional culture.

Blonde on Blonde’s raucous country-flavored blues-rock becomes Modern Times’ dancehall Bob Wills hip-hop; while the frustrations and ire of a young man become the knowing disapproval and sly disenchantment of a seasoned veteran. Across 40 years, then, two dimensions of Dylan remain constant: the surreal romantic poet and the musical alchemist, remaking the American musical tradition over, and over, and over again.

In Dylan’s world, the career of Joni Mitchellsubstituting her confessional mode for his experiential stance; her journey through world music/jazz fusion for his Americana excavationsprobably comes closest to a narrative of sustained, sequential invention. Unfortunately, she succumbed to the cultural slump we all experienced in the late 1980s, just as he was getting his second (or was it third? ... or fourth? ... or fifth? ... or sixth?) wind.

In the 20th century, the figures Dylan most resembles, I think, are Pablo Picasso and Miles Davis, both of whom were equally protean and restless pioneers. All three achieved astounding longevity, remarkable consistency, and demonstrated the ability to continually challenge themselves as well as their audience(s).

But of those three, Dylan is alone in bridging the 20th and 21st centuries, just as he is in employing the methods of the ragman, working almost exclusively in cast-off and borrowed materials, while patterning his work in the mythopoetic consciousness of the surrealists. He remains, in fact, “the raw essence of individuality in a sea of conformity ... His message is all between the lines and he delivers it like nectar that can drill through steel....”

Confronted with dynamic spirits like these, bent on incessant creativity who also want absolute control their own art, we tend to pick out the wrinkles that most irritate usPicasso’s womanizing, Miles’ anger, Dylan’s weirdnessmissing the cleanly delineated, majestic arc of the larger narrative. We’d rather believe, for example, that Dylan’s purported motorcycle accident was something like a tragic bolt of lightning rather than a conscious ploy on his part to retreat from public life.

In much the same way, the view of masterpieces now (Modern Times) and masterpieces then (Blonde on Blonde) obscures the 40 years traveled betweena back-highway tour crammed with roadside attractions. How long is 40 years? A couple of generations? A dozen trend-cycles in our super-heated, youth-oriented culture? Long enough for regret at parting and social outrage to be replaced by lifelong disappointment and rueful acceptance?

A young music-writer friend recently told me he’s glad that he came of age in the early 1980s because he can revisit Dylan’s music from before that time and hear it as something new. What my own experience with Modern Times suggests, though, is that Bob Dylanin 1996 or 2006 is an artist whose work will remain new, and challenging, no matter how many times it’s revisited.

No one’s sure, even, exactly how many songs he’s written (likely more than 1,000and most songwriters would be happy to have written any one of them). And his output is so prodigious, we’re lucky to have had time to listen closely to even a meaningful percentage of it (does anyone remember, for instance, an album called Dylan from 1973, covering mostly folk-revival favorites by other songwriters?).

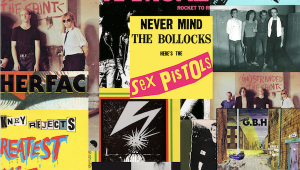

Never mind the various personas he’s donned as “ringmaster general” civil rights worker, folkie badboy, pop icon, Gypsy troubadour, durable rock warrior, riverboat gambler, cowboy bandleaderand all the while, his has undeniably remained “the voice in the wilderness of your head.” Working at such a high level of accomplishment for all those years: there’s no reason to doubt the rumors of his having been short-listed for the Nobel Prize.

An ancient source of wisdom counsels, “When you’re young man, be a young man; when you’re a middle-aged man, be a middle-aged man; when you’re an old man, be an old man.” On Modern Times, all the hip references and celebrity name-checking aside, Dylan leaves no doubt about his age, leaving us in the recording’s final verse with an image as bleak and time-weary as any he’s rendered:

Up the road, around the bend;

Heart burnin’, still yearnin’,

In the last outback at the world’s end.”

But the songwriter and cowboy bandleader’s own vitality should dissuade us from being taken in too far by such a tragic outlook. Disillusionment, after all, has always been part and parcel of Dylan’s philosophical traveling kit; in part, it’s what’s allowed him such consistent efforts at rejuvenation (... “when you ain’t got nothin’, you got nothin’ to lose...”).

But by remaining “forever young” in both 2006 and 1966, the 65-year-old Dylan has once again reminded us once again of the true calling of art, its moral purpose, if you willnot to perpetuate prevailing conventions, manipulate other for profit, or minister to passing social anxieties, but to remain true to itself and challenge us to renew ourselves, in modern times, in ancient times, all the time.

- Log in or register to post comments