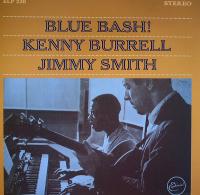

Smith-Burrell Combo Equals Tasty Licks

Listening to a straightforward, blues/gospel-drenched comping session like this reminds you that jazz has lost its soul today and aims mostly for the head. There’s nothing wrong with that, but it’s good to get back to the essential, visceral nature of the genre. This set, recorded in New York at an unidentified studio or studios on three days during the summer of 1963, let’s you know why.

Smith on Hammond B-3 and Burrell on hollow- bodied electric will have you tapping your feet in no time, propelling you away from your everyday cares. Smith adds chop and texture while Burrell produces smooth, gliding surfaces. The pairing is a recipe for long-term musical listening pleasure.

It’s a relatively short album (about 16 minutes a side) in which Burrell and Smith establish an easy rapport, trading licks and sending the good vibes back and forth with an ease that’s difficult for a non-musician to understand how such a mind-reading feat is possible. These guys make it seem easy and perhaps on this set of mostly familiar tunes, it is.

Smith gets center stage on some tracks while Burrell takes stage-right (left channel). The drums, played on various tunes by Mel Lewis and Bill English are panned hard-right. Milt Hinton and George Duvivier produce bass support.

Burrell and the drummer switch sides on some tracks and because those tend to feature more reverb and somewhat distant miking, I’d guess those are the Rudy-engineered tracks. Compare the more closely miked, drier-sounding opener, “Blues Bash,” with the next track, “Travelin’” with its reverberant backdrop and distantly miked drum kit and you’ll hear what I mean. Whoever recorded the opener, it’s a sound I prefer, though the reverb does add more atmosphere and depth.

The sound on this not so well pressed LP is on the warm, liquid, relaxed and forgiving side. Without an original for comparison it’s hard to say how this compares to an original.

What’s the deal with the pressing? Well, side two has some “shhhhsing” at the beginning, a sure sign of “non-fill,” which is when the vinyl begins to harden before it can fill the groove’s every nook and cranny. There’s some noise elsewhere as well on this thin and undersized disc, but it’s not a major irritant.

What do I mean by “undersized?” I’m reviewing a VPI Super Scoutmaster turntable right now that has an outer ring that you put over the platter once the LP is on it. The ring holds down the record’s outer edge to both eliminate minor outer edge warps and to better couple the record to the platter.

The ring misses the record by a good margin because the record’s diameter is so undernourished!

Physically, the groove area is replete with tiny “pock marks” and “wrinkles,” indicating a less than stellar pressing that has more in common with mass-market LPs from the ’70s and ‘80s than what we’ve come to expect today from records, but overall, if you can ignore the few minor “shsssing” noises, the pressing sound, despite its less than stellar physical attributes, is actually more than acceptable, especially since Sundazed/Euphoria doesn’t charge audiophile style prices ($18.98) for these Universal Music Group-sourced titles.

I’m sure Sundazed’s Bob Irwin is even more exercised than am I about Uni’s boneheaded decision to close its Gloversville, NY pressing plant, which Irwin had whipped into shape and had producing really superb 180g LPs back before the current vinyl groundswell.

And I’m sure Irwin pleaded to the Uni brass even more intensely than did I to please keep the plant open. It was making money from what I was told, but there was more to be made (at least in the short term) by shutting it down and selling the assets. It made the bean counters look good that year and pretty stupid now that UMG is lurching back into the vinyl business.

I’m not sure where this was pressed but wherever it was, they need to do a whole lot better.

- Log in or register to post comments