They seldom come up on the used market and even when new they weren’t made for very long. Now with Musical Fidelity sold and so few in circulation, I think I would think twice before purchasing. But I would now expect prices to be much lower than a few years ago. Still, a beautifully sounding turntable.

Analog Corner #104

The M1 weighs almost 50 lb. Its modular design begins with four large, handsome feet of mil-spec metal, (material not specified) each of which incorporates an outer rubber O-ring that fits over the foot's post, and a soft insert of orange elastomer that serves to damp the post from the foot itself and to isolate the upper plinth. Once the feet are positioned appropriately on a precisely level surface (the M1 itself has no leveling system), the acrylic platform incorporating the motor assembly is lowered over the four posts until it rests on the O-rings. The upper acrylic platform containing the bearing assembly and aluminum arm housing is then lowered onto the posts, which fit into recesses machined into the bottom of the acrylic. The top of the motor assembly and its tall pulley post protrude through a circular cutout in the upper platform. The bearing-platter chassis is thus isolated from the motor.

This approach is not novel, but it's effective when correctly implemented. One potential problem with such a design is if the upper platform's horizontal compliance permits excessive displacement, which can vary the distance from motor pulley to platter and thus affect the platter's speed of rotation. When Andy Payor attempted this approach in his original Capella 'table, the combination of a heavy upper platform, a high-compliance air-suspension system, and a linear-tracking, air-bearing arm of relatively high moving horizontal mass, created sufficient displacement to affect speed stability. That proved not to be a problem with the M1.

Once the platform is assembled, it's time to place the 12.7-lb platter—two slabs of acrylic separated by peripheral aluminum cylinders, to which are affixed thin elastomer pads—atop the inverted bearing's shaft, attach the SME tonearm to its platform, and place the round cross-section rubber belt around the platter and motor pulley. Other than installing and aligning the cartridge, and attaching the motor's DIN plug to the outboard power supply, assembly of the M1 is now complete.

Design details

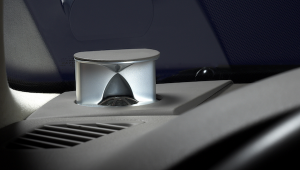

Musical Fidelity states that the M1 "uses the most expensive brushless DC motor available." And of that model of expensive motor, MF claims they select only the samples with the lowest levels of noise. The power supply is outboard, but the knobs for switching platter speed (331/3 and 45rpm) and adjusting pitch are conveniently located on a plate atop the motor. The platter speed is controlled via a motor-mounted optical sensor that monitors the shaft speed, then feeds the resulting information into a 16-bit "fuzzy logic algorithm" that controls the DC drive voltage. The M1's speed accuracy is claimed to be within 0.2%.

Protruding from the plate atop the motor is the 1"-tall motor spindle, a V-shaped groove machined around its girth. This is daring design—if not perfectly machined and polished, such a tall, gleaming shaft will, as it spins, appear to wobble far more than the usual squat, thin motor spindle, to which is affixed a wider-diameter pulley. How that pulley is affixed is critical to speed consistency, for even if the pulley is perfectly machined, if it's snugged down with a single set-screw, it will end up being slightly eccentric—and on this precision-sensitive playing field, "slight" is "great." Two or three set-screws will alleviate the problem, assuming they're carefully and symmetrically tightened (footnote 1).

In choosing a V-grooved pulley and a round O-ring belt riding in a V-grooved platter, Musical Fidelity's concept runs counter to those of such well-respected turntable designers as Andy Payor and A.J. Conti, both of whom argue that, when it comes to belt drive, a flat belt driven by a crowned pulley offers the best speed accuracy and consistency. I wouldn't bet against Payor's ideas in this arena, but because my reference Simon Yorke Designs S7 'table also features an O-ring belt and a grooved platter, I'll cut Musical Fidelity some slack on this.

Finally, there's the main bearing, which is key to a turntable's quietness. Musical Fidelity has chosen an inverted design manufactured from mil-spec, high-carbon steel ground to better than 5µm tolerance, with a 0.1µm surface finish. The platter rides on a high-quality carbon-steel ball machined to a spherical accuracy of better than 2µm. The bearing outer shell, built into the platter, is made of high-tensile stainless steel with a mil-spec brass insert with an integral lubrication spiral. The contact point between the shell and bearing is a Teflon pad built to close tolerances.

An SME tonearm

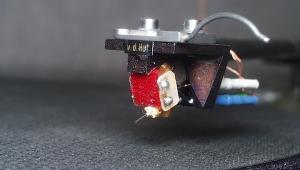

Built from some new and many familiar parts, the new M2 features a straight, lightweight armtube of stainless steel and a detachable magnesium headshell (also used on SME's Model 10 arm). If you're at all familiar with SME arms, you'll recognize many of the M2's parts and design concepts, including the basic mounting platform, the cueing lever, the antiskate mechanism, and the auto-locking arm rest. The M2 is available in lengths of 9", 10", and 12". Musical Fidelity's specs claim a length of 11", measured from stem to stern (back of threaded counterweight stem to tip of headshell), but who measures that way? In fact, the M2 supplied with my M1 was the 9" version, which was fine by me. I'll trade infinitesimally greater tracking distortion for greater rigidity and lower moment of inertia every time. The dual ball-race bearing system appears similar to the one used on the arm supplied with the SME 10.

The M2 generally follows SME's standard setup system. The headshell has fixed holes, so overhang is set by sliding the mounting base fore and aft. But instead of the smoothly operating geared mechanism found on more expensive SME arms, you slide the M2's base plate manually after loosening two clamping screws—not as convenient, but it keeps the price down. Otherwise, setting overhang is accomplished using the same basic gauge supplied with other SME arms. It fits over the spindle and features an outline of the arm and a tiny dimpled X where the stylus goes. You slide the base fore and aft until, when viewed from above, the armtube and headshell conform to the drawing and the stylus remains in the dimple.

Another clamping screw locks the threaded plastic arm pillar that's used to set VTA. Once it's loosened, you rotate a knurled surrounding knob to move the arm up or down. Not the system for obsessive VTA tweakers, but more than acceptable for most of us. VTF is set via a tungsten counterweight riding on another threaded shaft. It includes a system for setting VTF without an external gauge, but most users will want the comfort of a more exacting measurement via an external gauge. Antiskating force is set via the familiar method of weight, monofilament, and grooved post.

I've auditioned many SME arms, and this was the first one where the tiny dimple on the alignment gauge was not stamped in the exact center of the X. That made precise setup a bit more difficult than usual. I trust my sample was an aberration. Better me than you!

I also was somewhat surprised by the slight amount of bearing play I could feel and hear when giving a slight pull on the arm. This is not normal for an SME arm, in my experience. I assume my review sample of the M1 came with an early edition of the arm, but if I were Musical Fidelity, I'd check the play on each tonearm before packing it with the 'table. I am not used to feeling or hearing any play with SME arms.

Setting up the M2 arm was relatively fast and foolproof, although manually sliding the baseplate back and forth made getting the correct overhang tricky. Overall, though, rational choices have been made to reduce costs without impinging too much on performance—though I'd give up the convenience of the removable headshell to get the extra rigidity of a fixed design.

Setup and measurements

The M1's unusually tall, flat-topped spindle is machined to a very tight tolerance; many LPs in my collection offered a bit more resistance than I'm used to before they slipped down onto the platter. But better that than too loose a fit, and in general, playing records on the M1 was easy. The supplied brass collet-type clamp was rather lightweight, and no matter how much I turned the knurled knob to tighten it, it wouldn't grip the spindle with sufficient force to lock on to it. To improve the clamp's grip, I tried tightening the collet by twisting the knob with the spindle not inserted. That closed the collet grooves too much—I couldn't get the collet to fit over the spindle until I spread the grooves with a screwdriver. Don't try that at home. Interestingly, when I tried using a spare SME precision-machined, collet-based clamp I have on hand, it wouldn't fit over the spindle. Perhaps Musical Fidelity made the spindle diameter a bit too wide? In any case, the clamp needs improving, though that's a minor issue.

Flip the motor-mounted switch to 331/3 or 45, and when the platter gets up to speed, the adjacent LED turns from orange to green. You're ready to go. Should you vary the platter's rotational speed by ±6% or greater (using a second knob on the motor plate), the LED reverts to orange, telling you that you're no longer at the standard speed.

Before listening to any music I performed a few tests, the first being to check the M1's speed using Clearaudio's excellent 300Hz strobe record and light. (The record is grooved so that you can play it while measuring, to account for stylus drag, if any.) The disc indicated that the M1 was running slightly slow, but when I adjusted the pitch upward, the smallest amount I could deflect the pitch control increased the speed by too much, and the 'table ran fast by an undetermined amount. Since new 'tables often need "run-in" before playing at the correct speed(s), I let the M1 spin for a while, then tested it again. The 'table then ran at the correct speed with no pitch correction applied; measured with a hertz-reading voltmeter, a 1000Hz tone measured 999Hz, or about as good as it gets. The 'table's speed remained consistently accurate throughout the review period.

After the initial speed check, I performed a stethoscope test by placing the 'scope's receiver on the lower plinth and turning on the motor. Sure enough, I could easily hear the motor whirring up to speed, and a consistent noise thereafter. But there was complete silence when I placed the stethoscope against the upper plinth, which indicated that the isolation system—at least when it came to keeping motor noise from entering the playback mechanism—was working as advertised. Tapping a finger on the stand and on the lower plinth also confirmed the effectiveness of the isolation system.

When I played a record with the preamp muted (Classic Records' 200gm reissue of Peter Gabriel's third album, I heard almost complete attenuation of music's vibrational energy with the stethoscope placed on the arm-mount platform walls, but when I moved it to the upper plinth's acrylic surface, it got much louder. This makes sense, as the mechanical energy generated by the stylus/groove interface travels in both directions: up through the cantilever and into the arm, and down into the platter. The closer the stethoscope got to the motor cutout—the area with the least rigid support—the louder and more distinct the music became.

Finally, with a newly acquired Leader wow and flutter meter (thanks, Wally Malewicz), I measured the M1's flutter using a 3kHz tone. Wow proved more difficult to measure, as the concentricity of the record is far more critical when measuring low frequencies, and none of the test LPs I had on hand was perfectly concentric. Musical Fidelity claims 0.15% weighted wow and flutter; I was able to confirm that excellent flutter measurement. However, keep in mind that these measurements are probably extremely subjective—what's measured not only depends on the turntable but also the tonearm geometry, the cartridge compliance, and their interactions with surface irregularities. Keeping the LP and cartridge consistent can help in comparisons, but if the tonearms are different, and if one is damped and another is not, the comparison is probably not valid.

So what did the M1 Ssound like already?

With the excellent Transfiguration Temper W cartridge installed in the M1-M2's headshell, I sat back to listen to a few dozen LPs. Believe me, if this is work, I won't retire until I can't hear anymore. (For some of you skeptics, I know that means now. No such luck.)

My initial perception of the M1 was one of quiet—quiet and smooth, with outstanding midbass control and fine bass extension and dynamic expression. Overall clarity, transparency, and rhythmic certainty were all impressive for a $5000 integrated turntable, as was the M1's resolution of low-level detail. More important, the entire sonic picture had a pleasing coherence and a lack of obvious coloration that made picking apart the presentation extremely difficult. The M1 is a well-designed turntable, no doubt and no mystery about it. It spun quietly at the right speed, was well isolated both from the outside world and from its own drive system, and comes with a tonearm of good pedigree. Its weakest mechanical link would seem to be its less than totally effective evacuation or damping of the energy created at the stylus/vinyl interface.

I'm no big fan of acrylic as a platter material. I'm convinced it has a signature sound. (In fact, any material will have a distinctive sound, no matter how well-damped, rigid, and/or nonresonant it is claimed to be.) Acrylic is a convenient material to use for turntables because it's not hideously expensive and is relatively easy to machine. It's also said to have many attractive mechanical attributes (footnote 2), and it looks cool, as the M1 demonstrates. Acrylic is an excellent material for building inexpensive turntables, but based on my listening, I wouldn't want to spend $10,000 on an acrylic-based turntable, no matter how good the bearing and pulley machining. That's why, while I greatly respected the Basis Debut and consider it a world-class 'table, it wouldn't be my choice. I prefer a presentation with more punch and greater focus. Of course, one man's punch and focus might be another's resonances and colorations.

That's a can of worms I don't want to open. Considering how many highly regarded turntable platters are made of acrylic, I may hold a minority opinion. But to my ears, acrylic platters tend to have an attractively smooth, quiet sound, with a slightly soft and forgiving character. Midbass and bass, in particular, seem to soften and spread somewhat, while high-frequency transients exhibit a pleasing clarity and organization, but at the expense of the sharpness and clarity heard at live performances. Acrylic is better for French horns, worse for cymbals.

To help rout these prejudices or confirm my perceptions, I recorded a number of reference tracks using the Alesis Masterlink digital recorder. First I played them on my reference rig of Simon Yorke S7 'table, Immedia RPM2 tonearm, Lyra Titan cartridge, Walker Audio Motor Controller, and Vibraplane isolation stand. Then, after moving the Titan to the M1, I recorded the tracks a second time. The phono section was the ASR Basis Exclusive. (You may wonder if it's fair to compare a $5000 rig with one costing around $16,000. I did it because the M1's performance was good enough to make the comparison worthwhile, and because, in its press releases, Musical Fidelity habitually invites comparisons with "far more costly units," and usually for good reason.)

The tunes were Davy Spillane's "Atlantic Bridge," from Atlantic Bridge (Tara 3019); "Bluesville," from the stupendous 45rpm edition of Count Basie's 88 Basie Street (Acoustic Sounds AJAZ 2310-901); Respighi's Suite No.1 (Balleto), from Ancient Airs and Dances (Mercury Golden Imports SRI 75009); and an excerpt from Michael Praetorius' "Dances from Terpsichore" (Archiv 198653 SAPM, reissued by Speakers Corner and highly recommended).

These very revealing tracks told me everything I needed to know about the M1's sonic performance compared to my reference. I stand by my acrylic prejudices, though of course the arm variable has to be taken into account, as does the undamped energy I heard with the stethoscope, which could also account for a slightly smoother, softer, less focused delivery compared to my far more expensive reference.

On the Spillane track, which features noteworthy bass extension and dynamics set against Béla Fleck's banjo, Jerry Douglas' Dobro, and the bodhran (a handheld drum with head of stretched goatskin), the instant comparison demonstrated both just how good the M1 is, and where it falls just short of a rig costing more than three times as much. The M1's sound was definitely somewhat softer and less focused, the bass not having quite the explosiveness, the banjo sounding slightly more muted, The distance between the music and the reverberant field seemed somewhat less distinct with the M1, but I did note that the M1's noise floor consistently seemed somewhat lower, its backgrounds "blacker," which resulted in outstanding resolution of low-level detail.

The Praetorius track was particularly revealing, as it includes a great deal of transient information, including the sharp, buzzy-sounding regal, a small renaissance organ rarely heard today. Its raspy sound stood out in greater relief through the expensive rig, but taken in the context of a $5000 'table complete with SME arm competing with one costing more than three times as much and sitting on an active Vibraplane, the M1 was plenty good!

Once the Titan was mounted on the M1, I spent three weeks listening to it almost exclusively. Whatever I missed about my reference rig was not so great that I felt in any way seriously deprived. That's because, other than shaving off a bit of sparkle here and some bottom-end whomp there, and pulling back the overall dynamic scale a few notches, the M1 made no serious tonal or timbral mistakes. That's the sign of an accomplished design.

Vinyl happiness for $5000

At $5000 complete with a fully adjustable SME tonearm, the Musical Fidelity M1 occupies an interesting niche in the turntable market. The price traces an interesting line among a number of other acrylic-based 'tables—from Basis, Clearaudio, etc.—that, once you add a Rega RB300, a stripped-down Graham, or some other tonearm, are either more expensive without offering more features, or less expensive while offering fewer features. I can't say how they compare to the M1 because I haven't heard them, nor can I say how the M1 compares with the less expensive, non-acrylic Rega P9. I sure wish I had them all here for a shoot-out. Your choice in metal 'tables at this price are a German Acoustic Signature model and perhaps a few others of which I'm not aware.

As for the M1, it was easy to set up and use, features effective isolation, looks good, and is beautifully machined throughout. Its sophisticated drive system with pitch control is particularly impressive for the price. Once again, Musical Fidelity's design goal of providing "outstanding value-for-money coupled with excellent technical performance and great aesthetics" has been met. You can put the finest cartridge on the M1 and be assured that you're getting most of what you've paid for. (To get it all, you'll have to spend a great deal more than $5000 on a turntable and tonearm.) Although it's not inexpensive, the M1 would be a great way to go.

Footnote 1: On her La Luce turntables, Judy Spotheim solves this problem by freezing the motor shaft so that it contracts sufficiently to accept the tight-fitting pulley. When the shaft returns to room temperature, it expands to create a snug, symmetrical fit that doesn't require a set screw.

Footnote 2: One such is the (unconfirmed) fact that acrylic's vibrational impedance is very similar to that of a vinyl LP, hence stylus/groove-induced vibrations in the disc are not reflected back to the stylus at the LP-platter interface as they would be with heterogeneous materials.—John Atkinson

Sidebar: In Heavy Rotation

1) Otis Redding, Dock of the Bay, Sundazed 180gm LP

2) The Thrills, So Much For the City, Virgin 724358 180gm import LP

3) Oliver Nelson, The Blues and the Abstract Truth, Impulse/Speakers Corner 180gm LP

4) Nina Nastasia, Run to Ruin, Touch and Go TG241 180gm LP

5) Rubinstein, Brahms, Sonata in f, JVC XRCD JM XR24010 CD

6) Andrew Hill, Passing Ships, Blue Note 724359041728 CD

7) Begoña Olavide, Salterio, M•A Recordings MO25AV 180gm LP

8) Wayne Horvitz, Forever, Hi-Res HRM2001 24/96 DVD-A

9) NRBQ, Interstellar—Live 1970, Sundazed 10" 180gm LP

10) Bob Dylan, Rolling Thunder Review, Classic 200gm Quiex SV-P LPs (3)

- Log in or register to post comments

...the "first published date" info was not published simultaneously with the posting leading to confusion among early readers.

When I saw the posting over the weekend, the 2004 date was there, as I too asked when was this initially reviewed. It was there.

The original date definitely wasn't there this time when this article first appeared on Analogplanet. It usually is but it's been added since. There always seems to be an element of confusion with maybe one poster who doesn't notice the original publication date but the extra comments regarding the date this time appear to show that something was amiss.

Not that it greatly matters in the scheme of things of course.

It was already posted, but you may have seen the post earlier. I knew it wasn’t a new review as this turntable has been long discontinued, sadly.

i like these older pieces, as MF sez, many of these have not been put online before. it's good to offer them to a new audience.

But I really don’t understand why it is felt necessary to post these old reviews, can someone please enlighten me?

There were times when I wasn't a Stereophile subscriber and wasn't in the market for a new table. Seeing these old reviews reminds me what I missed. Why not post these old reviews, I wish more magazines would do likewise.

"My Analog Corner columns published in Stereophile have never before been posted online. That's a total of 280 columns. Slowly these columns are being posted on AnalogPlanet. Sometimes the columns include reviews of no long available products."

I have never seen some of these old columns, and they're quite interesting.

Anyone have one they might be willing to part with for a song?