Mr. Natural: Recording Engineer Bill Porter Part 1

Back in December of 1986, I flew to Denver, Colorado to interview the great recording engineer Bill Porter. Part II of that interview has already been published on musicangle.com.divided into multiple parts If you search Porter’s name you’ll find it. Why was part II published before part I? Don't ask! As promised, here’s part I of part I MF

Note: The intro that follows was written in 1986

Face it: Too many of today’s popular music recordings are garbage. I just slipped Bryan Adams’s new album Into The Fire on the Oracle. It’s a Bob Clearmountain co-production (with Bryan Adams). Although he’s responsible for popularizing the Yamaha NS 10M as a nearfield studio monitor (thereby earning him a place in my Hi-fi Villains’ Hall of Shame [along with Dr. Amar Bose]), Clearmountain also co-engineered (along with Rhett Davies) and mixed Roxy Music’s Avalon, a musical classic and one of the finest recordings in the modern rock ear. So I was hopeful.

A few bars into the first cut, it became obvious that the recording of Adams’s new album is “state of the art” awful. It’s ridiculously bright and harsh, wit thin, pinched, spitty sounding vocals fro a singer whose pipes produce a much warmer, fuller sound. The drums sound synthetic and pathetic. No bite to the cymbals. No kick to the bass drum. No snap to the snare.

The whole thing is smeared across a dimensionless, washed-out something or other. I won’t dignify it with the word “soundstage.” It must have taken a lot of hard work to produce a recording that could reduce my stereo to sounding like a rental-car radio.

What does this have to do with Bill Porter? Fortunately, very little. Porter, whose engineering career covers over 7000 recording sessions, has a sonic track record that puts him pretty much at the head of the popular-music recording field.

Those 7000-plus dates yielded an incredible 300 chart records, 49 top 10, 11 Number Ones, and 37 gold records. In one month of 1960, Porter-engineered recordings accounted for 15 of Billboard’s top 100 singles.

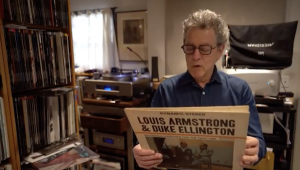

Porter’s odds of achieving such pre-eminence were not hurt by the artists he recorded, who include Elvis Presley, the Everly Brothers, Roy Orbison, Chet Atkins, Floyd Cramer, Homer and Jethro, Ann-Margaret, and Buddy Rich. But only those of you who have never heard, or seriously considered, his work could deny his importance in their recording career successes.

The “Porter Sound” (if something so utterly neutral could be described as a “sound”) is ultra-dynamic and extremely wide-band. Bass is of the intestine-shaking variety. The top end seems to sail on into infinity, without a trace of the pinched, sandy glare found on many of today’s productions. The resulting “see-through,” natural presentation of vocal and instrumental timbre occurs on a soundstage that is cinemascopic and deep, with individual instruments and voices exhibiting holograph-like solidity.

While Porter went for natural sound, he was not against pulling a sonic sleight of hand: As he pointed out, the big soundstage, was, in fact, a grand illusion. RCA’s Nashville Studio B, where Porter did most of his great work, was a smallish, problematic room. In addition, equipment in the studio was primitive by today’s standards, making the results that much more astonishing. Regardless of where or what he was recording, Porter got that natural, open sound. He got it out of RCA’s studio, Monument’s, and his own. You can hear it on tumultuous rock and roll recordings (Elvis), on easy-listening instrumental country music often referred to as “countrypolitan” (Chet Atkins), and on vocal fluff (the Browns).

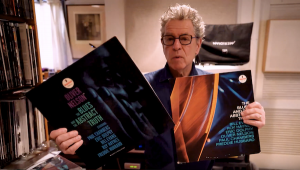

The sound Porter achieves is so pleasing, you find yourself listening to music you otherwise might dismiss. Like the Browns. Their sentiment is one big, sappy Hallmark card, yet I listened through both sides of The Browns Sing Their Hits (RCA LSP 2260), mesmerized by the natural, “chest and heady” tone and three-dimensionality of each voice and the clearly delineated space in which the group sang.

The calendar may be moving forward, but comparing any of the Porter recordings I’m fortunate enough to own with the new Bryan Adams album (or most contemporary pop recordings) makes clear that the state of the art has regressed back to the sonic cave-painting days.

How did Porter do it? I thought it would be worth the trip to the University of Colorado, Denver (where the 55 year old St. Louis native teaches recording engineering), to ask him in person.

I arrived on the cold, snowy campus the afternoon of December 8th (1986). Porter’s hospitality (and a bowl of hot soup) had me warmed up in no time. With his snow-white beard and head of hair, Porter seemed like the perfect person to talk with just two weeks before Christmas.

He had two classes that afternoon, so I went along, more than happy to oblige his request that I talk to his students. To the budding engineers, I recounted my Dopey Drive days on the Disney lot, supervising the Tron soundtrack. With Porter’s history of rock and roll class, I reminisced about my various, often-hysterical encounters with rock stars.

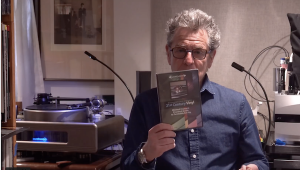

As Porter drove me to my hotel that night, the snow really began to fall. The plan was to meet early next morning at Listen Up, a High End audio store that owner Walt Stinson had graciously arranged to have opened early for our listening session and interview. Snow delayed Bill’s arrival by about two hours; but from then on, everything went according to plan.

The system in Listen Up’s premier room, which was reserved for our exclusive use, consisted of a Goldmund turntable, T-3F arm and Carnegie cartridge, the Mark Levinson ML 10A preamp, two ML 20 amps, and Goldmund Dialogue speakers wired with double Kimber TC-8 cable.

Porter began his career doing television sound. In 1959, hearing that Bob Ferris, the engineer at RCA, was being transferred out of Nashville, Porter decided he would be the replacement. Every afternoon for two weeks he sat in Chet Atkins’s office, asking for the job. His persistence paid off: After being interviewed by executives from New York, Porter got it. Salary? $145 a week!

Porter began working at RCA the last day of March, 1959. Nine weeks later he had recorded his first million-seller. While at RCA, Porter engineered the recordings for which he is best known. Porter left RCA under less than pleasant circumstances in 1963, moving on to a short stint at Columbia Records’s Nashville studio, followed by two-and-a half years managing Fred Foster’s studio, where many of Porter’s Monument label recordings were made.

He bought a Las Vegas recording studio in August of 1966 and moved out there with his family. Despite problems with equipment, bad RF interference, and nearby rumbling railroad tracks, the studio prospered. In 1969 Elvis Presley came to town to play at the International Hotel (now the Las Vegas Hilton). Presley’s producer at the time, Felton Jarvis, brought some 8-track masters over to Porter’s studio for some horn overdubs.

Unfortunately, all eight tracks were filled, so Porter had to add the horns live, while he mixed the track twice: once for mono and once for stereo. Next time Presley returned to Las Vegas, January, 1970, he asked for Porter’s help doing the live concert mix. Elvis was so happy with the studio-like results that he insisted Porter go on tour with him to mix the sound.

In 1973, a mysterious fire (Porter couldn’t talk about it; the investigation has recently been re-opened on the basis of new evidence) destroyed the Las Vegas studio. Then, in 1975, Porter was offered a job at the University of Miami where he helped develop a highly regarded four-year program leading to a degree in music, a minor in electrical engineering, and much hands-on studio experience.

While teaching there, Porter continued to go on the road with Elvis. He was changing planes in Boston on the way to a gig in Portland Maine when he got the news that Elvis had died.

Even though he was given tenure, Porter left Miami in 1981, unhappy with the steamy tropical climate and, after a short stint as the marketing director of an electronics firm, he went to work, for, of all people, Jimmy Swaggart (gasp!), doing live sound as well as record producing.

Last year the University of Colorado offered Porter a position similar to the one he’d had in Miami, and he jumped at the opportunity. He’s happy with his work and his home, about an hour outside of Denver, which he shares with his wife, Mary (Mary has since passed away).

Halfway through the interview, a number of Porter’s engineering students showed up. Most had never been exposed to High End audio. While their jaws dropped when they saw the stuff, it was the astonished look on their faces when we played some of Porter’s productions that I’ll never forget.

The Interview

MF: The studio in which you cut some of the greatest music in the history of rock and roll is now a museum. If you could return that equipment to service, would you be able to produce recordings that compete sonically with today’s “state of the art?”

BP: Yes! If I had a chance to do it like I wanted, technically, I think so. You’ve heard enough today from those old recordings to get a pretty good idea what used to be there…and listen, we did sessionstwo, three and four a day. How are you going to sit there and go to great extreme lengths? Back then you couldn’t do it. Today you can play around and get records that are technically perfect.

MF: Actually, after listening to the results you got then, the real question is, could you get the kind of results you got then, using one of today’s top studios? Obviously most of today’s engineers can’t!

BP: I think I could get better then I got then.

MF: In other words, the equipment can sound good, it’s just bad taste interfering so often?

BP: Let me put it to you this way. If I had the flexibility and the features of today’s equipment back then, I think I could have made much better sounding records.

MF: Is the problem with many of the recent recordings I brought along today the equipment, the engineers, or both?

BP: I think it’s producers, primarily. With the modern-day technique of trying to create the illusion of sitting in the lap of every instrumentthat is what they’re trying to do, essentially, and you can’t do it unless you do it piecemeal. The engineers are doing what they’re told to do based on what the producer wants. Now, whether engineers today get to offer any opinions, I don’t know. I always did, always ad-libbing, “Can we try this?” “Why can’t we do this?” And I was told “Yea. Go ahead. Find out what it sounds like.”

MF: There is a current production philosophy, even among some classical producers, that looks at a recording as something other than an attempt to capture a live performance. Sort of like the differences between a play and a movie, if you know what I mean.

BP: I’m somewhat of a purist, so from that angle…look I’ve made gimmicky records. (The Everly Brothers’s) “Cathy’s Clown” is a gimmick record.

MF: But it still has an honest musical approach.

BP: I had a tape loop in the drums to make it sound like it did. I like to hear (recorded music) as I hear it live, as if I were listening to it all at one time. That’s hardly done any more.

MF: Well, of course it is in “live” recordings, so maybe the easiest way for you to get more involved today would be “on location” gigs?

BP: Well, I really feel you can create the illusion of depth in recordingseven multitrackif you go about it with that in mind. That seems to be an afterthought. People try to make some attempt at [depth] after they put it all together. And they’ve made so many judgments detrimental to that type of sound that [they] can’t go back and recreate it. I still believe you can get that sound if you’re willing to go to all the trouble to do it.

MF: Then it’s more work and trouble?

BP: (emphatically) Sure it is! It takes a lot of work and a lot of trouble, because you’re basically going against that philosophy when you do multi-track recording; so you’ve got to go back and try to recreate that again.

MF: Where did you develop your “ear”; your insistence that music be recorded to sound utterly natural?

BP: That’s a very difficult question to answer. I don’t know. I heard a lot of live music in my younger years…

MF: That’s key right there! I get the sense that many younger engineers never have. Their only base of reference is some other engineer’s recordings. It’s easy to get separated from reality.

BP: To me, if you mike an instrument, you have to mike it in such a way as to get the tonal balance of that horn or strings or whatever. And many engineers today would put the mike right on top of the instrument, so it doesn’t even have a chance to breathe. The sound has to radiate out into the air, and you’ve got to get back far enough to get that overall sound. That was my basic approach to miking techniques.

I learned some from watching early miking techniques in television. There really weren’t any books available. And it was fly-by-the-seat-of-your-pants. What felt right, by what you heard. Now, I was the kind of engineer that went into the studio to hear what was being played, acoustically. Then I’d have some idea what it would sound like in the control room.

With the multi-miking techniques they have now, you can get an entirely different mix from what the arranger intended without even thinking about it. So if I could recreate in the control room what I heard in the studio, I knew I was doing the right thing. Of course, back then everybody played together and everybody played so they could hear each other. That interaction, right or wrong, is missing in today’s recordings.

MF: There’s a signature in your recordinga natural signature, but I think now I’d recognize one of your recordings. It’s a certain balancewhat is it?

BP: Could you describe a little bit better what you’re trying to tell me?

MF: Oh great! Well. There’s a spaciousness. An openessa three-dimensionality, not only of the ensemble, but of each instrument and the singer as well. And there’s a certain ambience. You wouldn’t call it a particularly “wet” sound and yetand there’s a kind of neutrality about it. Does that help?

BP: Well, of course, most of the stuff you heard was the RCA studio, and that studio acoustically was not very good.

MF: You sure fooled me!

BP: Well you heard the big band record initially?

MF: Yea, well that was a problem.

BP: That’s how the studio used to sound. The room had a lot of standing waves in it. A lot of coloration. And I was unable to get RCA to do anything about it…so this is really a band-aid approach, but it seemed to work: I took about 50 dollars out of petty cash and got a bunch of fiberglass panelsthe kind you put in ceilingsthe old type covered in Mylar. And I cut them into triangles and hung them from the ceiling at random heights all over the room.

MF: Again, more trial and error. Today things are more mobile. Engineers go from studio to studio; how can they possibly know what they’re dealing with in each location?

BP: [Many] engineers I know bypass the console and everything else and use their own mixing board to get the microphones into the tape machines. Then they go back and recreate what they want later on. That way they know their equipment and they’re not at the mercy of what somebody else has done.

MF: Obviously you were instrumental in Roy Orbison’s chart successes, just by the sound you got. When he moved over to MGM, he didn’t have any more hits.

BP: That’s right.

MF: Why didn’t he insist that you come with him?

BP: I never could figure that out. Orbison never, as far as I’m concernedand I’m not saying anything bad about the guy, because I really like himbut he never understood the engineer’s contribution. It’s as simple as that.

- Log in or register to post comments