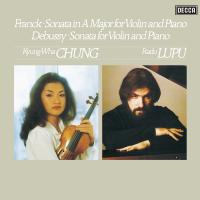

Chung/Lupu—Franck and Debussy Sonatas For Violin and Piano

I first heard one of their efforts about 5 years ago when they reissued the vaunted 1988 Bernstein recording of Mahler’s Symphony No. 2 with the New York Philharmonic, but since that time I had yet to revisit the label until now. When I saw the name Kyung-Wha Chung come up under their new releases, I knew I had to hear it. South Korean violinist Kyung-Wha Chung may not be as well-known as she used to be, but in her heyday she was responsible for many definitive recordings of major violin repertoire, including my personal favorite recordings of both the Tchaikovsky and Sibelius violin concerti (Decca SXL 6493).

This new reissue comes from a Kingsway Hall recording with pianist Radu Lupu, done in 1977 and issued on Decca in 1980. It features two of the premiere French violin sonatas of the repertoire: the “Sonata in A Major” (1886) by Cesar Franck and the “Sonata for Violin and Piano in G minor” (1917) by Claude Debussy. Both Franck and Debussy were leaders of French musical composition in their respective time periods. Franck (1822-1890) reveled in his influence, with well-known students such as Vincent d'Indy, Ernest Chausson, and Henri Duparc.

The composer and organist was known primarily for his focus on reviving chamber music in the French musical tradition, and his use of the ‘cyclic form’ where melodic material is recalled throughout multiple movements of the same work. He used this effect most notably in his “Symphony in D”, the only major orchestral composition by the composer still widely played today. The form is also found here in the “Violin Sonata” which was written as a wedding present for the violinist Eugene Ysaÿe and has remained in the repertoire of great violinists ever since, becoming popular enough to be transcribed for many instruments such as cello, viola, double bass, flute, oboe, and even a violin concerto with orchestra. “Allegretto ben moderato” the first movement serves as the work’s thematic grounding, gently introducing the melodic material almost like a rhapsodic introduction before the second movement which some consider to be the piece’s “real” first movement.

The “Sonata” by Claude Debussy (1862-1918) on side 2 however, is a stark contrast in both music and personality. Debussy was an iconoclast who often lamented the importance critics and music academia placed on his works. Despite this, he was perhaps more influential in shaping the course of musical composition than almost any other composer operating at the turn of the century, creating not just the musical concept of impressionism (inspired by the earlier painting movement), but changing the formal, melodic, and tonal idioms for generations of composers to come. The 1917 “Violin Sonata” was the composer’s last finished composition and was part of an uncompleted series of six planned sonatas Debussy wanted to accomplish in the short time he had left, dying from cancer and wearied from the emotional toll of WWI. Unlike the serious nature of the Franck composition Debussy’s three-movement sonata is short and filled with sparks of joy and playfulness mixed with bouts of expressive melancholy. The piano and violin interact with an improvisatory-like banter, and quick changes of tempo and mood are found throughout all three movements.

Despite these wildly different works, Chung and Lupu navigate them brilliantly. This is not simply a one-off recording session with two well-known soloists thrown-together in a booth. This recording expresses a deep understanding of this music, and intimate collaboration between two master artists. On the Franck especially the two players give a reading that is refined, sensitive, and intimate. Lupu serves not as an “accompanist”, but as the melodic equal of Chung, and the two adapt well to each other’s playing and personal styles. Chung is clearly a virtuoso, with impeccable intonation, control, and technique, but that all plays second to her thoughtful phrasing, tasteful ebb and flow, and keen understanding of the musical structure. Both players give and take rubato with enough liberty to give the performance an organic quality but are restrained enough to prevent any lugubriousness or distraction from the piece’s natural flow and forward motion. This is romanticism for the thinking man; passionate, but nuanced.

Given that this is a Kingsway Hall recording, we know the sonics are going to be good. Granted they are not up to the glorious standards of those classic tubey 2000 series Deccas from the prior decade, but there is still a wonderful naturalness to the presentation that lets you know it was recorded in a great acoustic space. Chung’s violin is clear, resonant, with plenty of dynamic range. Lupu’s Piano is perhaps not captured as brilliantly as the violin, with transients in the lower register a bit more rounded than I would expect to hear were I in a real recital hall, but this is hardly an uncommon complaint. The piano in the first few bars of the second movement of the Franck has a fury of melodic runs that come across clear and powerful, matched by the intensity of the violin taking over the material. Whatever quibbles I might have about how the piano was mic’d evaporate when I hear these two players interact.

I think the highlight of this entire record is the “Recitativo- Fantasia” (mvmt 3) where both soloists really show their musical bona fides, with plenty of room for free-flowing, cadenza-like phrases and a wide range of dynamics and colors. Chung’s pianissimo is so strikingly beautiful, clear and pure, you almost wish she would remain there for eternity. There are many wonderful and highly regarded recordings of this staple violin recital piece. I own a wonderful rendition recorded just a decade before by Itzhak Perlman and Vladimir Ashkenazy also on London/Decca (CS 6628). That recording features star players and good sound too, but with a very different musical interpretation. At times I did appreciate the more strident and expressive moments from Perlman and Ashkenazy, but I did notice it brought more focus to the individual musicians and less to the music they were playing. The real reason to favor this recording of the Franck over others is the flow Chung and Lupu are able to coax out of musical transitions, and even between the movements themselves which flow effortlessly into one another, never breaking the tension they had worked to create.

On the Debussy, which is admittedly less of a warhorse, these players show their versatility and rise to the more playful and wild style without any sense of effort on their part. The runs at the beginning of the Finale are tricky, Chung not only nails them with exacting precision, but with the forward motion and joyful bursting nature that appears in so much of Debussy’s music. The phrasing follows with grip and vigor the erratic lines of the composer, adhering to every dynamic which is often a pitfall players encounter in this music, leading to a performance of mezzo-mush. I have not heard every recording of this piece, but so far, this one is by far my favorite.

I was impressed by this recording’s sound quality, but just to compare, I went out and found an original London pressing (CS 7171). By 1980 Decca had moved their record pressing plant to Holland, and the sound quality of their releases was nowhere near that of their 60s heyday, but I had always wondered how much of that was recording vs mastering vs pressing. Well, I’m happy to report that this Analogphonic reissue is superior in every way to the original Dutch pressing which I found to be too dark, with a much more limited dynamic range. Gone on the original Dutch pressing is the beautiful full resonance of Chung’s violin found on this reissue. A great portion of Radu Lupu’s sonic energy lost on the original has been restored on this reissue.

Was there more tape noise on my reissue? Yes, but that’s going to happen with any mastering from an old tape (unless you filter the sound to death). There is a pressing of this record from the wonderful Japanese King Super Analogue reissue series done throughout the 90s, but spending close to $200 on a record for the sake of comparison is not an undertaking I felt compelled to mount.

For us analog devotees who don’t have an unlimited vinyl budget, you can rest assured that this reissue from Analogphonic will bring excellent AAA sound to what is one of the if not the definitive recordings of this marvelous repertoire. Is it an audiophile marvel like some of the Living Stereos or Deccas from 20 years prior? Perhaps not, but this recording is no sonic slouch either and vastly improves upon the original release thanks to an excellent remastering job by John Webber at Air Studios in London. The real reason to buy this album, however, is the chance to hear two masters pour their heart and soul into a performance of such substance and quality that few, if any performers, living or dead, can match.

Michael Johnson is a Phoenix, AZ based oboist and audio writer. He is currently a member of the Tucson Symphony, and performs regularly with the Phoenix Symphony and Arizona Opera. He is a contributing writer at Audiophilia.com and maintains a vinyl-focused youtube channel by the name of PoetryOnPlastic. You can follow his vinyl journey on Instagram at instagram.com/poetryonplastic

(This record currently is available at Elusive Disc.