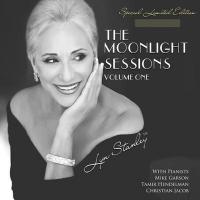

Lyn Stanley's Daring “The Moonlight Sessions- Volume One”

All of this is what her fans expect and she gives it to them. Here she goes a few extra steps, or should I say two fewer. The vinyl uses the “one step” process that’s not new but was recently resurrected by Mobile Fidelity. Lyn calls her version “SuperSonicVinyl™” (the graphics that explain it in this album’s insert uncomfortably knock off Mo-Fi’s). No doubt everyone reading this now grasps what is the one step process but in case you don’t read the review of Mo-Fi’s Abraxas where it’s fully explained.

This record is the first of two “The Moonlight Sessions” volumes, the second of which will soon be released. The revolving cast of “name” musicians is impressive: Mike Garson, Christian Jacob and Tamir Hendelman on piano, Chuck Berghofer on bass, Ray Brinker Bernie Dresel and Joe LaBarbera on drums, Luis Conte on percussion, John Chiodini on guitar, Chuck Findley on trumpet, Rickey Woodard on tenor saxophone, Bob McChesney on trombone, and Hendrik Meurkens on harmonica.

You can search any or all of them and you’ll find impressive credits. And of course the recording engineers are Al Schmitt and Steve Genewick at Village Recorders (where completely by coincidence I ran into Lyn while on a tour of L.A. Studios. Lyn was kind enough to briefly allow me [and my video camera] into the session), as well as at Capitol and LAFx.

Lyn had told me she’d had the arrangers weave classical music themes into the charts, which sounded like an interesting idea. The album opens audaciously with “All or Nothing At All” the song written in 1939 that catapulted Frank Sinatra to stardom when he joined the Tommy Dorsey Band. The song was recorded with the Harry James orchestra eighty years ago to the day that I’m writing this. At the time it sold poorly (8000 copies) but once Frank’s star rose Columbia reissued it in 1943 and it went on to sell a million copies.

This is a forlorn song in which the singer is ending an unsatisfying relationship, explaining to his former significant other that in love it’s “All or nothing at all”, that in this relationship it’s been “half a love”, and that “half a love never appealed to me”. Could it have been put more coldly? Only at the very end could the lyric and especially in Sinatra’s reading be thought of as one final challenge for the full measure of love, but that’s a considerable stretch.

Lyn’s version begins with Chuck Findley’s solo trumpet playing a mournful variation on the “Rhapsody in Blue” theme, which sounded appropriate for a song about dissolution and regret but from there it all goes horribly wrong, with Rawlins’ chart and Stanley’s singing turning this into some kind of steamy, dangerous drama. It really isn’t.

The song is an after the fact declaratory “kiss off”—a look back at what was and what might have been. It’s a regret-filled “it’s over” song.

If you don’t think so, listen to either Frank’s original or his later “swinging” but still brutal version arranged by Nelson Riddle on the Strangers In the Night album (or play your own record). Hell, listen to Bob Dylan’s masterful take on Fallen Angels. No, Bob’s not got much voice left but he too knows how to tell a story and turn a phrase.

Ms. Stanley’s odd version, from the arrangement’s sultry, luxurious mambo rhythm to her seductive singing simply doesn’t make sense. This is not a seduction song, nor should there be any drama other than in the bridge, which the arranger inexplicably turns into a breezy bounce that’s at odds with the meaning and would trip up even the most experienced vocalist.

All or nothing at all

Half a love never appealed to me

If your heart, never could yield to me

Then I'd rather have nothing at all

After the opening few bars that set an inappropriately “saucy” tone Ms. Stanley chooses to “bite” the microphone with a startling, accentuated island of an overdramatic “all” that attacks and decays and disconnects from the “or nothing at all”. Rather than saving the bigger (but not too big!) dismissive “nothing” for the second verse repeat, Ms. Stanley delivers it in the first.

The trumpet then enters with an inappropriately “sexy” rather than wistful fill and then comes the elegantly written, stinging declarative line “half a love never appealed to me”, which, with a straightforward delivery would devastate (Frank excruciatingly drags out the “half”, using it as a dagger) but instead here it gets a choppy rendering that swallows the crucial “half” in “half a love” and overinflates for unknown reasons the “never”.

The line is supposed to be derisive and dismissive, not dramatic. The drama in this relationship is essentially over though as always in love affairs, a dangerous residue remains that shows up in the bridge. That line demands but doesn’t get a flat, dispassionate, dismissive reading.

The next two lines (“If your heart…nothing at all”) explain the break up in bleak, disturbing, accusatory terms: “you never gave me your all, so I’d rather have none of you”. But why the heavy accent on the word “rather” when the key word is “nothing” in the phrase “nothing at all”?

All or nothing at all

If it's love there is no in between

Why begin, then cry for something that might have been

No, I rather have nothing at all

The reiteration of the song title in the next go round of course can’t add anything to the first because the “nothing”’s been fully and prematurely exploited. Lyn’s best delivery is the line “If it’s love there ain’t (she changed “is” to “ain’t” and it works) no in between” but then it’s back to a too big “Why” and a mysterious pause between “that” and “might have been”.

Why is any of this sung seductively and/or dramatically if she’s telling an ex the unsatisfactory relationship is over? If there’s any emotion to be drawn it’s the singer’s regret and hurt. Frank delivers the hurt on the older version and the derision in the later one. Lyn delivers none of that. She seems more interested in cozying up to the microphone and impressing the listener (you) with her singing.

Then comes the “bouncy, swinging bridge” where the song should have an injection of regret and especially of danger and vulnerability (listen to Frank’s version) but instead turns rhythmically “jaunty” and skips along almost gleefully, forcing Ms. Stanley to sing joyfully and with bounce “but please don’t put your lips so close to my cheek” (all that’s missing is the Vegas “hey”!) when it should be delivered as either a haunted plea or perhaps as a threat as in “back off”.

The singer admits to still being vulnerable and so rejects the former lover’s enticements begging: “please don’t bring your lips so close to my cheek, don’t smile or I’ll be lost…. I could fall and be caught in the undertow”, before steeling him/herself with so I’ve got to say “All or nothing at all”. That “all or nothing at all” is not a “put up or shut up” but rather a statement of “nothing at all” fact!

There’s no way to successfully deliver this song as an enticement or an attempted seduction but that’s what the arrangement pretty much demands and since Lyn Stanley produced, she’s got to take full responsibility.

The merry bridge gets a second, even merrier go round in a post-musical solo reprise. That one turns unintentionally comical in Ms. Stanley’s unusual reading of the line “so you see, I’ve got to say no, no”. You might argue that the closing triumphant exclamatory declaration of “All or Nothing at All!” is a “put up or shut up” one last chance challenge to the ex, and a “surprise” ending, but if that’s the angle, this version makes even less sense.Thus the album opens with a bizarre rendition of a great song I never again want to hear, well recorded though it is.

I picked apart that one song because it’s emblematic of why this album, while Lyn Stanley’s most ambitious and musically eclectic, is also her most ill-conceived, in great part because it was self-produced. With no outside force to put a brake on some really bad ideas, Ms. Stanley was free to self-indulge as in some cases were the hired musicians and arrangers.

Once you’ve gotten past “All or Nothing At All” you get to a cover of “Willow Weep For Me” wherein Lyn’s swoopy, over-exaggerated, elongated “weepiness” quickly becomes cloying. And again she’s singing seductively “come hither”, this time to a tree. And if that’s not what she’s aiming for why is it amplified by Rickey Woodard’s even more annoying burlesque-style tenor sax growls? Were those his or her idea? Is she singing in character or trying to seduce audiophiles?

Are you familiar with Sinatra at the Sands where Frank’s backed by The Count Basie Orchestra and on “I’ve Got a Crush On You” one of the sax players does a salaciously comic growl and Sinatra stops singing, laughs and says “you want to meet Monday and we’ll pick out the furniture”? Well on this track Woodard (who is a talented, experienced player) follows Stanley around (musically) laying down similar salacious growls but not for comedic effect. It’s just too much (this is again repeated on “Girl Talk”). It’s not “sexy”. It’s creepy, especially on a song in which the singer is metaphorically looking for shelter from a broken heart. Again, this reading makes no sense. If you want to hear a clean, fresh version, listen to June Christy’s with Stan Kenton.

The first side of this double 45rpm set side ends with Glenn Miller’s “Moonlight Serenade” with a thankfully understated, elegant Christian Jacob arrangement (featuring a gorgeous Chuck Findley trumpet solo) that demands from the vocalist elegant phrasing, precise control and most especially, given the wide open spaces and Lyn’s insistence upon “in your face” fully exposed miking, first class interpretive skills.

Honestly, though Lyn’s surrounded herself as always with great musicians and has yet again improved her vocalizing, she’s not yet fully realized any of those, particularly in her interpretive skills, which leave many of these songs devoid of depth and resonance, which she attempts to cover with road blocking pregnant pauses, hyper-enunciation and a few other diversions. The halting, breathily delivered opening lines of “Moonlight Serenade” are excruciatingly hyper-dramatic and completely inappropriate. Why accentuate “stand” in “I stand and I wait”? There are dozens of “why”s in this and in every song here because I’m not sure Lyn has imagined a back story, invested herself in the character she’s playing and considered that woman’s life history, or the person to whom she is singing, or the place, or any of the pre-singing “prep” needed to bring life to a song.

So while there are a few fine moments of vocal promise, many of those, like some impressively long held notes, or skillfully turned phrases that do show Stanley’s growth as a singer, they tend to stand out almost as ‘stunts’ intended to showcase technique rather than as organic elements of a musically realized whole vocal performance.

Thus the overall results range from passable, okay and pleasantly surprising, to flat, stilted, repetitive, devoid of genuine, heartfelt emotions, ill-conceived and occasionally flat-out embarrassing (“My Funny Valentine, “Embraceable You” and “Crazy” are painfully hollow).

With but a few years of experience, Lyn Stanley has daringly chosen a repertoire well-covered by some of the greatest singers of our time and presented her voice “out front” and unadorned in the mix. Few singers, even the most experienced put themselves “up front” this way. I don’t know why she did it.

Give her credit for daring, but her phrasing, where she too often substitutes pregnant pauses and volume shifts for genuine drama and emotion, remains unsure and sometimes clumsy, her control, particularly of volume, unsteady, and her diction over-pronounced, unnatural and sterile.

But aside from all of that, there’s one fundamental problem Lyn needs to address that I only gleaned after listening to 22 female vocalists for an Analogue Productions compilation for which I’m writing the liner notes. They include Ella Fitzgerald, Jennifer Warnes, Janis Ian, Joan Baez, Joan Armatrading, Patsy Cline, Julie London, Dusty Springfield and others—as well as after listening to Diana Krall’s excellent new album Turn Up the Quiet. And that is Lyn’s “fourth wall” problem.

As with either stage or film acting, when you sing it’s critical to not break the “fourth wall”, which is the one between you and the audience. You need to keep that distance and block out the audience even if as on stage you might turn towards it. Break the wall and the illusion is destroyed. You can only establish the desired emotional connection and intimacy with the audience by keeping your distance.

On just about every track on this album Lyn not only breaks the “fourth wall”, she denies its existence and sings directly to the audience. She’s “in your face” and it’s not comfortable.

I went back to Krall’s new record and it made for comfortable listening even though there are obvious flaws in her vocals. It’s not perfect, but that’s what makes it human and engaging. But more importantly she’s definitely not singing to you! She’s keeping her distance and singing the story, which makes you, securely situated behind the “fourth wall” an observer, comfortably listening in.

Since I've known Lyn for a few years now, writing this review was not comfortable either, but listening made me more uncomfortable, and glossing over my true reactions would only have compounded my discomfort. The sound is stupendous and if you enjoy these performances don't let me or the $99.95 price tag stop you. This recording is available on 45rpm "one step" vinyl, hybrid SACD and reel to reel tape. Volume II coming soon.