"Pan"-Demonium Breaks Out As Mo-Fi Issues "The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan"

In the early 1960s Columbia was a "classy" label that did not do no rock'n'roll and it certainly wasn't a label big on folk music. That would be Maynard Solomon's Vanguard or Folkways. So when Dylan's debut stiffed, the pressure was on.

But John Hammond knew what he was doing and Dylan followed up with this album issues in 1963 when he was but 22 years old. It opens with "Blowin' In The Wind," a song that Peter, Paul and Mary would turn into a worldwide hit. It was a gentle plea of a song that pushed the civil rights movement to the forefront of America's consciousness and it helped establish Dylan as the "spokesperson of a generation"—a role he says he never sought that became a burden he was determined to shed.

But what else could he have thought was going to happen when he issued an album with powerful message songs like "Masters of War," "A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall," and "Talking World War III Blues"? But just to make sure he's not pigeonholed, Dylan flips the scene and delivers the tender "Don't Think Twice, It's All Right."

This was a tumultuous time for Dylan and eight recording sessions took place between the Spring of 1962 and 1963 at which songs were recorded, re-recorded, tossed and revised. New songs appeared quickly and were recorded. Dylan hired Albert Grossman as his manager, Grossman and Hammond didn't get along so jazz producer Tom Wilson (who later worked with Frank Zappa and The Mothers of Invention) took over as producer.

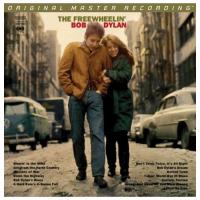

Among the events that affected the album: Dylan's girlfriend, the late Suzy Rotolo (pictured with him on the cover), left for Europe and Dylan pined for her. He was scheduled for "The Ed Sullivan Show" where he wanted to sing "Talking John Birch Paranoid Blues," which had been recorded for the new album but CBS said "no," and Dylan walked out on the booking.

Four songs planned for the new album, including the John Birch Society song were scrapped and the album was re-sequenced to what became the familiar album, but not before a few copies of the original made their way out of the pressing plant. Those became a "holy grail" find for Dylan fanatics.

While some sessions included backing musicians, only one of those takes ("Corinna, Corinna") made it to the final album. All of the tracks feature Dylan singing, accompanying himself on guitar and occasionally on harmonica. For Columbia engineers, recording in "stereo" was not about presenting the singer/guitarist in a space as audiophiles might want. Instead the engineer put a mike on Dylan's guitar and one on his voice that also picked up the harmonica.

In producing a "stereo" mix, whoever did it decided to put Dylan's voice in the center, his guitar in the right channel, and when he switched to harmonica, pan it to the left channel. Unfortunately, the mixer's panning hand wasn't as fast as Dylan's switch from vocals to harmonica so when you listen you'll sometimes hear Dylan's voice shift to the left channel for a split second before the harmonica kicks in, or you'll hear the harmonica fly to the center for a nano-second before Dylan resumes singing.

It's an unfortunate artifact of an attempt to produce a "stereo" mix in the early "separation-crazy" days of early stereophonic reproduction. So there's a case to be made for issuing this seminal album in mono. That's been done by both Sony as part of a superb box set and by Sundazed.

Mobile Fidelity got the rights to issue the stereo version of this 50 minute album and chose to spread it out on a double 45rpm set. The attraction here is the astonishing transparency and transient clarity that no other version I've heard comes close to attaining and that includes a black "360 Sound" version, which is when Columbia was cutting with an all-tube chain, a white "360 Sound" version, and Sundazed's mono.

No doubt the mono version is more coherent sounding and one can only imagine Dylan's disgust at hearing the odd stereo panning—which assumes he even bothered listening. We know that when he finished Blonde on Blonde he hung around Nashville and took part in the mono mix after which he split, leaving the stereo mix to others. Either he was a mono man all along, or he became one after hearing this odd affair.

Don't get me wrong! This is easily the most transparent "you're in the studio" edition yet. Even though it's just a guitar strumming, a gravel voice singing and a high pitched harmonica squealing, if you know this album you're guaranteed to hear new depth and new details. If you've got a mono button, you can flip it and get the unparalleled transparency and dynamics (yes, guitar strumming and singing has wide dynamic range) without the panning, but even if you don't, it's worth putting up with a few odd pans to get the breathtaking sensation of being in Studio A as Dylan lays down these tunes. If anyone tries to tell you Bob couldn't really play guitar all that well, play them this record.

The gatefold packaging includes three super black and white shots of Dylan in the studio (so young!) and a color outtake of the cover shot taken further down the block where a Chevy Corvair van takes the place of the VW van on the shot that made the cover. Speaking of the cover, the quality of the cover art reproduction is superb.

Every other version I played sounded veiled and distant compared to this double 45. Mobile Fidelity has completely refurbished its playback and cutting chain, supervised by Tim DeParavicini. It's easy to hear. This is the best sounding edition of this album I've yet heard, "Pan"-Demonium or otherwise.