The Rear View Mirror: Alexander “Skip” Spence’s Oar

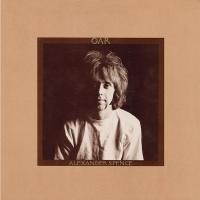

Upon Spence’s release, Rubinson encouraged Columbia to back Spence’s legal fees and musical ventures (plus a new motorcycle). Moby Grape had moved on, and Spence wanted to record songs he’d written in the hospital. Urban legend has it that following Columbia’s reluctant agreement, Spence in December 1968—dressed only in his pajamas—rode his new Harley-Davidson 900 miles from New York to Nashville. Rubinson gave Spence creative freedom and instructed Nashville recording engineer Mike Figlio to record every last second, though upon arrival Spence found himself not in a proper studio but in an editing room with an old three-track tape recorder. Throughout the next week, he recorded and overdubbed what became Oar, his lone solo album.

Oar’s legacy is complicated. Spence recorded these tracks only as demos, though Rubinson, who in New York sequenced and mixed the album, pushed Columbia to release it as is. Rubinson’s exact intentions remain unclear; a 2009 Crawdaddy feature portrays him as one of Spence’s few supporters, but his original liner notes reek of exploitation. “This record is so guileless—so remarkably un-self-conscious, that its integrity is its unity,” Rubinson wrote. “It might have been polished—and dull. But after all—any dummy can be boring, and so very few of us can be truthful. Hear this music for the truth it tells.” By portraying the schizophrenic-diagnosed Alexander Spence as more authentic and “truthful” than the “stupendously produced Great New Groupswhogotsixhundredthoutosign,” Rubinson pulls the dangerous “troubled genius” marketing myth. (The liner notes don’t mention Spence’s mental health difficulties, though even a cursory listen to Oar provides strong evidence.) Reports claim Spence recorded these demos in good spirits, yet the actual compositions are dark and lonely.

Not that those liner notes produced the desired results. While Greil Marcus at Rolling Stone found it “some of the most comfortable music I’ve ever heard,” Robert Christgau called Oar “[the] strangest record of the year, slow and lugubrious, completely lacking the explosive energy Spence used to bring to Moby Grape when he called himself Skip and swung axes at people; by anyone else it would disappear immediately.” Even then, it “disappeared immediately;” a year after its release, Oar was by far Columbia’s worst seller (some speculate it sold fewer than a thousand copies) and got deleted. Edsel Records reissued it in 1988, and throughout the 90s Sony and Sundazed reissued it to increasing fanfare. Before Spence succumbed to lung cancer in 1999, industry executive Bill Bentley prepared the More Oar tribute album featuring Robert Plant, Beck, Tom Waits, and others. Two decades after Spence’s death and five after Oar’s original release, the record remains controversial. It maintains only a cult following, and critics don’t often mention it (though The Wire listed it as one of “100 Records That Set The World On Fire [While No One Was Listening]”). It sharply divides audiences: is Oar an accidental masterpiece, or the nonsensical ramblings of an acid casualty?

When analyzing Oar, Alexander Spence’s mental health struggles must be remembered—after all, it’s a crucial part of the record’s context—but they can’t overshadow it. It’s also important to view his work apart from the “troubled genius” canon, whose existence only represents society’s problematic glorification and aestheticization of mental health issues. Spence, for all his odd behaviors and addictions, was also human, and he did not sacrifice himself for our consumption of his art (nor did Alex Chilton, Elliott Smith, William S. Burroughs, Kanye West, or any other so-called “troubled genius”).

Oar’s first established trait is its unique recording style: sonically transparent technically, though communicating as ghostly and a bit veiled. With gaping space between the hard-panned sounds, it seems like it could only exist in a space closed off from any literal or metaphorical light. The instruments, all recorded by Spence, are often out of sync with one another, and the juxtaposition between his unpolished albeit measured vocal performances and his sometimes aggressive instrumentation is unusual. Album opener “Little Hands” enters with bright acoustic guitar and wandering electric leads before a loose drum take emerges. Spence hazily sings about “little hands clapping all over the world” as if lamenting the loss of an idyllic childhood. It soon takes a dark lyrical turn that’s hard to precisely interpret: “Out in the street/The sick that you meet/How many friends do you call your own?” On “Cripple Creek,” meanwhile, he croons about “a cripple on his deathbed” who “left his wheelchair spinning deeper in the mud.” Whether intentional or not, some of these songs sound like cautionary tales, glimpses of life’s inherent risks and inevitable decay.

Much of Spence’s singing is only half-intelligible; on the almost hymnal “All Come To Meet Her” and the yearning “Diana,” his voice drifts off, as if his mind is already elsewhere. “Margaret-Tiger Rug” and “Lawrence Of Euphoria” both have a nursery rhyme’s playfulness, while songs like the dreamy “War In Peace” (whose outro interpolates the “Sunshine Of Your Love” riff) and the disturbingly direct “Books Of Moses” can be instrumentally and vocally confrontational and lyrically bizarre. “Weighted Down” and “Broken Heart” both express despair to the saddest extent: “A broken heart would be lovely/Broken on the ground/A knife stuck in the ribs of me/Would be better be found/Hanging tree blowing gently/A noose would be ignored/Then to stand upon the receiving end/Of the right hand of the Lord,” he sings on the latter. Contrarily, there’s “Dixie Peach Promenade,” which incorporates double entendres in a catchy, goofy manner before inevitably adding a grim detail: “I took every bit of stuff from A to Z.”

Oar’s 9-minute closer “Grey/Afro” explores a failing relationship that the narrator tries to salvage, with Spence’s hushed, alluring vocals casting the song in mystery. A winding bassline anchors the composition—his effect-warped drumming seems oblivious to the other sounds—which on newer reissues abruptly cuts off (it originally transitioned into the unlisted “This Time He Has Come”). No matter which ending you choose, Oar is a record of polar opposites placed side by side, drastically jumping between subjects and moods joined only by Spence’s cohesive sound and approach. His lyrics take all sorts of twists and turns, but Spence’s feelings of alienation always vividly cut through; that’s why Oar tribute projects, respectful as they are, never quite grasp its spirit. While David Rubinson’s original liner notes remain gross, he wasn’t completely wrong: Oar is a unique work of human purity that exists beyond any notions of psychedelia and mental illness. Unfortunately, addictions, hospitalizations, and behavioral issues further overtook Spence’s life, and he never returned to consistent musical activity. As Oar’s legend grew, Alexander Spence died of lung cancer in 1999, two days before his 53rd birthday.

Clean original Columbia 2-eye pressings are incredibly rare and expensive, and Sundazed’s reissues vary in lacquer cut and pressing; therefore, I picked up the more reliable 2011 Music on Vinyl pressing. Cut and pressed at Record Industry from 96kHz/24bit transfers of the original masters, the 180g disc is tonally bright (possibly too brittle and metallic for some) but with good channel separation still captures the recording’s unique magic. An all-analog Oar would of course be better, though who knows what is the tape’s condition and market interest. This MOV reissue has only the slightest dish warp, and while the foldover jacket is flimsy, it’s acceptable given the relatively inexpensive price. (Diehard Spence fans might also want Modern Harmonic’s AndOarAgain, an exhaustive 3LP alternate takes collection in a trifold package.)

(Malachi Lui is an AnalogPlanet contributing editor, music obsessive, avid record collector, and art enthusiast. Follow him on Twitter: @MalachiLui and Instagram: @malachi__lui)