Revolver Spins Seductively Psychedelic in AAA Mono Reissue

Smith wanted out anyway because Rubber Soul wasn’t really where his musical head was at and he felt it was a good time to move on—hard as it might be to believe that anyone would want to break an association with The Beatles. A few years later he began working with a new group signed to EMI called the Pink Floyd.

On April 6, 1966 The Beatles began working on their next album, which was eventually called Revolver but it had no name when they produced three takes of the first song recorded for it, which when fully produced would become the album’s final song “Tomorrow Never Knows”. What a way to start!

Promoted from disc cutter to Beatles engineer was an at first terrified 20 year old Geoff Emerick. Emerick’s willingness to experiment and break with rigid EMI engineering traditions was the key to producing the sonically groundbreaking Revolver. The Beatles themselves were demanding certain sounds and Emerick and others at Abbey Road including engineer Ken Townsend were more than willing to oblige. Townsend invented what became called ADT or “Artificial Double Tracking”. It allowed a single vocal take to become two by feeding the signal to another tape recorder running at a slightly different speed and then feeding the signal back to the original recording—all in real time. The Beatles, especially Lennon had gotten tired of doubling their vocals by recording it a second time.

“Tomorrow Never Knows” features Lennon’s voice fed through a Leslie speaker/amplifier system, which includes inside a spinning pair of horn speakers. The pioneering track also includes a wide variety of effects tape loops created by tape oversaturation, some “home brewed” by Paul McCartney. They’d run these loops simultaneously on up to five tape machines and record them to multitrack that Emerick would then “play” using the board’s faders. Revolver also features George Harrison’s first Indian music-flavored tune, one of three strong songs he contributed to the album.

While all of this was going on, the group found time to record the catchy single “Paperback Writer”, which astute listeners at the time noticed contained the French children's song “Frere Jacques” as a backing counterpoint to the main vocal, as well as the memorable “Rain”. For that one the rhythm section was played way faster than intended and then slowed down to the correct speed, producing mesmerizing instrumental textures. The vocals were similarly produced. Both songs were good enough for Revolver but were relegated to singles.

According to “The Complete Beatles” (Sterling Publishing) Mark Lewisohn’s highly recommended book (without which these reviews would not have been so context-rich) on April 27th multiple mono mixes were produced of 3 songs but all were rejected by the increasingly interested Beatles, who had previously left mixing decisions to others. Even so, Lewisohn writes “…they paid little attention to stereo. In fact, no stereo mixes had been done (at that time) for any Revolver songs.”

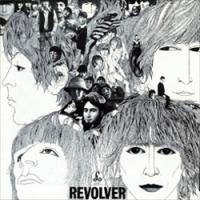

Audiophile types (guilty as charged) often complained about “Eleanor Rigby”’s strident sounding strings—a double string quartet. Seemed a shame it didn’t sound sweeter but it was in keeping with the colder, metallic sound of the entire album, perfectly captured by Klaus Voorman’s edgy black and white line drawing cover.

Emerick placed the microphones so close to the instruments they almost touched the strings. No wonder they sounded edgy! The song is just the strings, originally recorded to all four tracks, then mixed down to three, leaving one for McCartney’s overdubbed vocal.

Of course that version wasn’t the final one for these studio perfectionists. Paul re-recorded the vocal, double tracked with harmony and John and George assisted with some “aah”s and the “all the lonely people” part.

On June 6th 1966 four years to the day the Beatles first entered Abbey Road Studios, the boys spent the evening overseeing mono re-mixes of five album cuts. At midnight and for the next hour and a half, McCartney performed an additional “Eleanor Rigby” overdub.

Emerick employed the same close miking technique recording the trumpet/sax quintet backing for “Got to Get You Into My Life”, putting the microphones into the trumpet bells and then in the recording “limiting the sound to hell!”

The album was completed on June 21st with marathon mono and stereo mixing sessions (many of which were “tweaking” remixes of songs that had already been mixed and remixed more than a few times) and with one more song still needed, John contributed “She Said She Said”— as perfect a song about an LSD trip as has ever been written. Final mixes were on June 22nd and the album was released on Friday August 5th.

The American release cheated Beatles fans of the mesmerizing “I’m Only Sleeping” the charming “And Your Bird Can Sing” and “Dr. Robert” ironically about a real-life New York City based doctor who dispensed to his friends hallucinogenic drugs.

Was this the perfect pop/rock record? Who would say no? Forget the studio innovations littering the grooves. The songwriting was and remains stellar. Everyone steps up their creativity. George Harrison’s contributions are his best and most varied: a protest song— “Taxman”, his first Indian foray “Love You To” and “I Want to Tell You”, McCartney writes his most affecting song “Eleanor Rigby” and perhaps his most melodically engaging “Here, There And Everywhere, among others. And John Lennon’s “She Said She Said” and “Tomorrow Never Knows” would have been enough but he offered more as did McCartney. Only Ringo was unable to produce so the others wrote him the still charming “Yellow Submarine”, which provides some much needed levity on a mostly hard-edged album.

Consider that Revolver was released three years five months and seventeen days after Please Please Me. How was that possible? I don’t think anyone can really explain. You could probably write a book about “Tomorrow Never Knows”—about how it was made, how it affected studio recording from that day forward, and especially how it affected a generation of listeners during a very turbulent period of time.

As unsettling and unstinting as Revolver was, at the time, it resonated well with many college aged kids. For me (feel free to skip this part of the review written only because of encouraging reader feedback) it was a bummer of a time that I relive with every play. I had almost flunked out of Cornell’s School of Agriculture, having lost all interest in veterinary medicine. I wanted to move to the school of Industrial and Labor Relations, which was where many pre-law students went. Switching meant a semester in a netherworld “division of unaffiliated students” or some such Twilight Zone named group headed by a guy whose last name was "Rideout" as in "I'm going to ride you out of college"). You were given one semester to prove yourself. If you didn’t achieve a certain grade level you were out even if you passed every course. And I believe the deal was, only the top X number of kids in the division could move on, so it was not only your performance that counted, it was how well you did against others.

Sophomore year I lived in a fraternity house. Junior year you had to move out to an apartment. Most of the kids paired up but the fact is, for one reason of another none of them wanted me as a roommate. Maybe it was the loud music or my less than serious academic pursuits. I was a screw-off, which is why I was flunking out. Most of my frat brothers became doctors, dentists, friends of Hillary, college presidents, etc. so maybe they were right rejecting me!

The inseparable duo of Rosenberg and Friedman, two hangers on-ers/non-fraternity members asked me to room with them at 114 Ferris Place, Ithaca, NY—but only because they couldn't afford the apartment themselves. I remembered the address while listening to Revolver for this review, thank you. And I remembered much more! Such is the power of music.

They rigged it so that each had a bedroom while I got the living room. It was the biggest room but since it was my bedroom there was no living room and the apartment was strictly for sleeping and for them and not me, endless fucking, which was impossible to not hear since I had no door to close.

It wasn’t the biggest of deals since I had really buckled down to study and spent most of my time in the library studying so I wouldn’t flunk out and give my parents heart attacks.

At the time I kept a terrarium full of Venus Fly Traps in the unused kitchen. I kept it very well manicured. For some reason I couldn’t understand, every time I manicured the terrarium, Rosenberg and Friedman would come out of their rooms to watch. As I tweezed away the weeds, they let out pained grunts. It was weird.

Some evenings I’d return to the apartment to find the windows wide open in the middle of the Ithaca frozen tundra winter. The place was freezing. I’d ask Rosenberg and Friedman “What the fuck is going on here?” but was always met with zombie-like blank stares.

One night I opened the door and smelled it. I’d never before smelled marijuana but one whiff and it was obvious what it was. It immediately also became obvious why I’d often walked into a freezing apartment with windows wide open and what were those weeds I’d been plucking from the Venus Flytrap Terrarium and why they would wince. Also obvious at that point was the cause of their vacant expressions and bleary eyes.

I raged at them about my law school ambition and about how they were threatening my future with their illegal, immoral and dangerous behavior. How dare they! I told them I was leaving and going over to visit (names omitted). They were good students, serious kids, and about as likely to smoke pot as were the members of the Cornell Young Republican Club with whom I’d spent my first semester agitating on campus for the election of Barry Goldwater.

I got in my car, which was a really cool Austin-Healey 3000 MKIII (possible only because my father had saved for typical college tuition costs but at the time Cornell state school tuition for New York State residents was around $500 a semester so with money left over, he kindly indulged me with the car and I rewarded him by almost flunking out). On the other hand, an Austin-Healey convertible, which had a solid rear axle and ground clearance of a few inches was a seriously suicidal car to drive in an Ithaca winter so I sometimes think he was trying to kill me or I was trying to kill me.

So I drove over to my friends’ basement apartment to seek solace and comfort from slide-rule carrying engineering and horn rimmed glasses (now cool, but not then!) wearing liberal arts majors, all of whom comfortably fit in the “nerd” category. I had my opening self-righteous outburst ready to go.

I burst through the door and? And? And I immediately smelled it! They were busy passing around a joint and having a high old time. “What?” I said. “You too? I just left Rosenberg and Friedman smoking dope.”

“You, Michael, are the only person we know who doesn’t smoke pot. We’d have invited you over to join us but you have been so loud and self-righteous in your condemnation we didn’t bother. Now that you are here, sit down, relax and float downstream…” (or words to that effect).

Revolver sounded even better every play after that evening. My grades were good enough to transfer to Industrial and Labor Relations and the next year I moved in with those guys, bringing with me, my Dynaco PAS-3X preamp, Stereo 120 amp, Dual 1009SK/Shure V-15 and AR 2ax speakers. A splendid time was had by all, every Friday afternoon and throughout the weekend. During the week the combustibles were hidden in the garage and the stereo remained turned off as did we—end of multi-Revolver listening session induced ancient memories.

The Beatles had always admired the bass power of many Americans records compared to theirs and on Revolver they decided to find a way to pump up the bass—something that was obvious way back in 1966 to Beatle fans with decent stereos. The record had much more and powerful bass than had previous Beatles albums thanks to Emerick’s efforts. What’s also obvious and amazing is how McCartney’s bass playing on the album had also taken an enormous leap forward beginning with his startling riffs of “Taxman”.

I compared this reissue to UK and American originals and to the CD and the 1982 Japanese Odeon red vinyl reissue. In this case, given the generally harsh sound of the original recording, the CD fares pretty well, though it becomes ear-unpleasant as you turn it up. One level of the hardness is “digitally induced”, the overall picture is flattened and congealed and the percussive transients are coarse and smeared compared to any of the LP versions.

Even though the stereo mix obviously consists of pre-recorded elements mixed together into monophonic tracks hard-panned left and right, a case could be made for the stereo mix here, though there are weird distracting mix moments as on “Eleanor Rigby” where you can hear the mix engineer pan the main vocal during the chorus.

Once you read in detail how these tracks were recorded, their nakedness in the stereo mix—the way the individual elements are left exposed left/right—though interesting, become distractions, making the mono mix that much more attractive and of course coherent. Still, this is one album of which I’d be sure to have both mono and stereo mixes. McCartney’s vocal overdubs on “Here, There and Everywhere” and the backing “oohs” from the others make for fascinating listening even as they more effectively blend together in mono.

Interestingly, the mono reissue’s EQ is warmer than the mono original’s (true of the UK and American originals and the 1982 Japanese reissue) but much closer to the somewhat warmer sounding stereo original.

The red vinyl Odeon reissue was cut very hot on this title and no one will complain about a lack of bottom end weight (he prodigious amount of bass might have some complaining about too much bass), but the top end is certainly more strident than the original’s and of course that of the reissue’s. It’s more “hi-fi” than accurate in my opinion and spatially flatter than the reissue. On my system at least, it gets sonically annoying over time, whereas the reissue does not.

In general we're talking about minor tonal differences among these pressings (the revisionist Odeon pressing excepted) sure to be overwhelmed by your system’s character and especially by your cartridge’s particular personality. “Yellow Submarine” sounds especially warm on every version auditioned, analog or digital.

The mono reissue’s bass is deep and powerful but is not heard as a heavy-handed EQ choice as it especially was on the stereo reissue, where it’s heard as “bass” and not as the contours and textures of the instrument producing the bass.

The reissue’s transparency and depth surpass that of the original and there’s more detail to be heard even as the original’s overall upper midrange/lower high frequency range is somewhat suppressed on the reissue compared to the original’s purposeful, shimmering glaze. In this case I think most listeners will prefer the reissue. Don’t worry though. It’s not soft. I think the reissue was somewhat toned done compared to the original because most people now as opposed to then listen on speakers with far more extended high frequency response. McCartney’s sibilants on “Eleanor Rigby still sear. Find the ideal level and the balance will produce close-miked but not strident strings and a very present Sir Paul in your room. Interestingly the background vocals in the mono mix appear well behind McCartney as intended while in the stereo mix they are simply panned laterally, which is not nearly as effective. The more you listen to and appreciate the mono mixes the less you’ll appreciate the lateral separation.

Another perfectly flat, perfectly quiet record, too.

BTW: I didn't read what I'd written a few years ago about the stereo box set reissue. I think it's quite consistent with what's written here.