Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band Mono Almost 50 Years Ago Today!

Released as a single on February 17th 1967 with “Penny Lane” on the flip side, the double sided dose of nostalgia may very well have influenced The Kinks Are The Village Green Preservation Society and probably much of XTC’s Andy Partridge’s nostalgic output. Because singles were not included on U.K. albums both of these exceptional Beatles tunes were excluded from the upcoming Beatles album. And because by this time The Beatles controlled their albums worldwide, Capitol couldn’t chop up the next album and add the singles.

“Strawberry Fields Forever”, written by John Lennon about a Salvation Army home around the corner from where he grew up in Liverpool was perhaps The Beatles' most accomplished song, musically and technologically. It certainly was the group’s most innovative studio production. It included the first use of a Mellotron, a device invented in England, which was a primitive “sampling”-based keyboard instrument that used pieces of recording tape and multiple playback heads.

Fortunately for all involved (and especially John), by this time The Beatles were not on anyone’s schedule other than their own and they could take as much time as they wished to complete the song. Dozens of takes were involved not to mention too many overdubs to easily count. The final version was spliced together using two different takes performed in different keys and tempos at Lennon’s insistence despite George Martin’s insistence that it was impossible. As it turned out, splicing together the two takes was possible. Slowing down the faster, higher pitched take magically matched both the pitch and tempo!

“Penny Lane”, McCartney’s nostalgic exercise named for a street in a suburb south of Liverpool, took somewhat less time to complete though it was no less a perfectionist production commenced on December 29th but not completed for almost a month. A rejected mix made it to America as an advance broadcast single and according to Lewisohn, is among the most valuable Beatles singles.

Meanwhile production continued on songs like “When I’m Sixty-Four” (the final version of which was sped up a semitone to give Paul a more youthful sound), “Fixing a Hole” (recorded at Regent Sound because Abbey Road had previously been booked) and of course “A Day in the Life,” the history of which every Beatles fan should read in Lewisohn’s book. Ringo’s distinctive, syncopated drumming pattern on that song—his innovation—was copied by rock drummers for years hence.

“Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” was at first but a song and not an album title nor an album “concept”, until at some point soon after the first take on February 1st 1967 McCartney realized his tune could be used to launch an entire album performed not by The Beatles but by Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. It was also the first time his bass (or perhaps anyone’s bass) had been plugged directly into the board instead of recorded via a microphone placed adjacent to the bass amp.

George Harrison wrote “Only a Northern Song” for inclusion on the album but it never made the cut. It was yet another George bitching song (“Don’t Bother Me”, “Taxman” “Think For Yourself”, etc.), this time about his being a contract songwriter and thus cut out of publishing royatlies (50% to Dick James’s Northern Songs, Ltd., 50% to NEMS Enterprises Ltd. owned by Lennon, McCartney and manager Brian Epstein).

While most of the sound effects heard on the album were filched from Abbey Road Studios’ collection, the opening orchestral tune-up came from the mega-orchestra session produced for “A Day in the Life”’s enormous crescendo, while the audience scream used to hide the edit between the opener and “With a Little Help From My Friends” was extracted from the then unreleased recording of The Beatles at the Hollywood Bowl. According to Geoff Emerick, the glue that holds together the album concept—the sense of it being almost a vaudeville show—was also a McCartney concept.

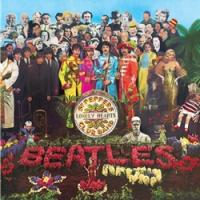

On March 30th photographer Michael Cooper shot the iconic, celebrity-saturated album cover featuring artist Peter Blake’s set, as well as the inside jacket’s close-up. Upon returning to the studio at 11PM, the group completed “With a Little Help From My Friends”.

The “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (Reprise)" was another brilliant McCartney idea. The 1’18” song was recorded in one eleven hour session in Abbey Road’s mammoth number one studio, usually reserved for symphonic and film sound track production.

Final assembly of a pop album with no “rills” (gaps) between the tracks began on April 6th 1967. This necessitated crossfades between the title song and “With a Little Help From My Friends” and between the reprised title song and “A Day in the Life” using three tape decks: two with the songs to be cross-faded together and one recording the cross-fade. These edits had to be accomplished for both the mono and stereo mixes and so it’s no surprise that these transitions produced among the most jarring differences between the mono and stereo records.

Engineer Richard Lush said “The only real version of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band is the mono version. The Beatles were there for all of the mono mixes. Then, after the album was finished, George Martin, Geoff Emerick and I did the stereo in a few days, just the three of us without a Beatle in sight. There are all sorts of things on the mono, little effects here and there, which the stereo does not have”. Emerick also states that almost all of The Beatles recording sessions were monitored through a single speaker.

Fourteen remixes of “Good Morning Good Morning” were required on April 19th to get a satisfactory bridge between it and the “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (Reprise). The enterprise was saved by a chicken cluck that well matched the song’s opening guitar note. Martin recalled it was by chance but Emerick disagreed claiming it required a time shift to match. Whichever it was, writing or reading this we can all hear it in our minds. Emerick said it sticks in his.

The famous concentric run-out groove gibberish was produced the evening of April 21st 1967. It was gibberish and not a secret message, whether you played it forwards or backwards. John Lennon suggested as a wake up call for dogs the 15K tone between the end of “A Day In The Life” and the concentric gibberish. Harry Moss added it during the disc cutting process, which took place for mono on April 28th and stereo on May 1st.

Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” was released a month later on June 1st, 1967 at the head end of “the summer of love”. That same day The Beatles went into De Lane Lea Music Recording Studios and recorded a crappy jam session, according to all accounts, best forgotten.

Revisionist music historians now downgrade the importance and quality of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, calling it “self-indulgent”, or a “musical dead end”, or the antithesis of rock’n’roll or whatever. Perhaps helping them to that conclusion was a John Lennon quote in a magazine interview in which he supposedly said “We don’t want to make another album like that rubbish.”

Lennon went through a post-Beatles period where he was the anti-Charles Mingus. Mingus would say about every record he made, regardless of its actual quality “This is the greatest record I’ve ever made” and Lennon would say the opposite.

In a later Rolling Stone interview Lennon was particularly vicious to everyone involved including George Martin, without whom it’s quite clear, The Beatles would never have happened and if they had, it probably wouldn’t have been as glorious a run as it turned out to be.

Martin, ever the gentlemen, semi-excused Lennon saying the “strange person” was never satisfied with anything he’d done, though Martin also said he “hardly forgave him” for the comments.

Once upon a time I couldn’t imagine how one could listen to a monophonic version of this album with its dazzling pans and spacious, three-dimensional soundstages.

I remember (uh oh! Here he goes again) walking into E.J. Korvettes in Douglaston, L.I. where when I was home from college I’d go weekly to see what’s new on vinyl and spotting this large display rack filled with hundreds of copies of whatever it was. It had to be a big group I figured, unable to read any print across the jacket. Of course when it turned out to be the new Beatles album, I bought it along with a few others I can’t remember.

I took it home (still living at home), got suitably “prepared” and because I didn’t want to wake the folks, played it on a pair of Koss Pro4A headphones. To say it was a dazzling, unforgettable experience buzzed on headphones, would be an understatement. All was fine until the foxhunt literally crossed my mind at which point I burst out into hysteria, unaware of the volume. Next thing I knew my mother turned on the light startling me. I took off the headphones and she asked if I was “high on potsy”. “You gotta hear this!” I said but she really didn’t and she didn’t.

Which reminds me of another story. In 1969 I'd invited some friends over for the first moon landing. By that time parental control was null and void and I no longer hid my vices. So we sat around the TV room smoking a joint watching and a short time later after the air had cleared my mother came down to watch with us. Maybe she got a contact high because as Armstrong was going down the ladder she said" Wouldn't it be funny if he slipped and said "oh shit!"? Then forever the first words of the first man to land on the moon would be "oh shit!"

Listening to this album in mono today, with more mature ears (“mature” in every way), (even compared to when I reviewed the stereo box set a few years ago and uh oh, just noticed same Koss Pro4 story, sorry) has me thinking that much of the “gimmicky” charge coming from detractors has to do with the ham-handed stereo mix. What might have been exciting fewer than ten years into the stereo era today sounds disjointed and almost incoherent. I’m not just writing that because of my enthusiasm for this box set.

When you hear elements panned here, there and everyone for no reason other than that they had to be put somewhere other than in the center, the rationale for it all falls apart.

Yes, a few tracks do work well in stereo, but they all work in mono. There’s more to hear and more obvious is the greater finesse that went into the mono mixes where all of the elements perfectly fit together into a far more cohesive blend.

When you read the recording history and consider all of the many overdubbing sessions, the instruments and effects added and subtracted to make the elements “just so” and how carefully they were blended together for the mono mix and not so for the stereo mix, I don’t hear how you could conclude that the stereo mix is superior (something I thought for decades, BTW).

Now when I hear the stereo mix I want to reach out and push it all together into the center! Never thought I’d think that—not even as late as a few years ago when I reviewed the stereo reissue. I’ve had mono copies for years but always played the stereo. This has been an educational exercise for my ears. I don’t think I’ll often play the stereo version but I will the mono.

There are many interesting though subtle differences between the stereo and mono mixes, like Paul’s more prominent screaming at the end of the reprise. You can literally hear the engineer start the applause playback too. Mostly though you’ll easily hear what how superior is the overall mix. The coherence in my opinion refutes charges that this is a “gimmicky” record. Instead what shines through are the musical and production innovations probably never again to be heard on any pop/rock recording by any group.

I compared this mono reissue with an original mono UK pressing, with an original mono American pressing, with the Japanese Odeon 1982 red mono pressing and with the mono CD box set version.

The original is not a hard, bright record. It is nuanced and well-textured overall, though when it’s intended to jar it does. After reading Lewisohn’s account of the recording I paid particular attention to the tabla recording on “Within You Without You”. Emerick remarked “The table had never been recorded the way we did it. Everyone was amazed when they first heard a table recorded that closely, with the texture and the lovely low resonances.” Also on the track is a dilruba—a bowed sitar-like instrument and a tamboura (a stringed instrument).

Comparing the various versions, the original UK pressing version has believable drum textures that you can feel and the “low resonances” Emerick extols have believable, almost rubbery contours. On the Japanese Odeon and on the CD the drum textures are hardened and cardboard-y (it’s cut far hotter than the others and levels were equalized for all comparisons). The “low resonances” have a harmonically indistinct quality and seem to turn off and on rather than develop, swell and recede. The overall picture is flat. The volume has to be turned down to make it sound pleasing. Not so on the original UK.

Play “When I’m Sixty-Four” and despite the pitch change the lead clarinet has a convincing woody roundness. It really sounds like a clarinet as does the bass clarinet as does the second standard clarinet. Listen to the tubular bell and the brushwork mixed well down.

The Japanese Odeon is harder, flatter and less engaging than the original and the bass is not as fully fleshed out. The brushwork is harder and coarser. Also, not that it’s critical, the ending gibberish is not in a locked groove. It’s there and gone.

That is what I feared the reissue might sound like but it doesn’t. It sounds remarkably similar overall to the original though it’s more dynamic and better extended on top (than my one -1 lacquer pressing so take into account).

When (if) you get this record, play first “Within You Without You” and you’ll hear to what Emerick was referring and you can turn it up to increase your pleasure and unless it’s your system talking, it will not harden and turn unpleasant. You’ll hear space behind the instruments and sense genuine depth missing from the Odeon. The differences aren’t subtle. What is subtle are the differences between the original and the new reissue.

I heard a bit more prominence on Harrison’s sibilants on this track but it’s smooth and doesn’t at all sizzle and since it’s not on every track it’s not a characteristic of the remastering. It’s on the original too but just not as prominent though the rest of the track sounds like a clone of the original. Perhaps it’s related to the number of plays the original has had. Whatever it is it’s a very minor difference.

What’s key is that there is not one overriding coloration heard on this or any of the reissues so far auditioned. The original is cut at a lower level than the reissue, the reissue is cut at a lower level than the Japanese reissue.

The Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band reissue is, in my opinion, another complete success. The pressing quality of my sample was like the others so far: perfectly flat and perfectly quiet.

Sadly for me, while the 15K tone was audible to me in 1967 and well beyond, I can’t hear it anymore on the original so I can’t tell you if Sean Magee added it to the reissue. Hell, I used to be able to hear the 15kHz “flyback” transformers of my neighbor’s televisions outside their homes too when I was a kid and UHF store burglar alarms too.