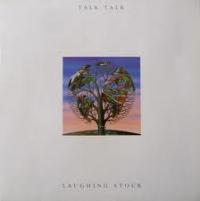

Talk Talk's 1991 Sonic Spectacular Gets First American Vinyl Issue

On this, the final Talk Talk album, his abstract lyrics indicate on one hand a grand spiritual ambivalence and on the other a deep concern about the consequences of losing faith.

For those thinking of the early synth/pop Talk Talk (or for some who confuse the group with the song of the same name by The Music Machine!), Hollis' subject matter may be surprising but not nearly as ear opening as the musical backdrop against which he sings them in a gloriously haunting voice that sounds part Bryan Ferry, part Scott Walker (not the cheesehead reactionary, obviously) and part Peter Gabriel on 'ludes.

Musically, it's a sublime and astonishing mix of Brian Eno, Miles Davis, Peter Gabriel, improvisational guitarist Derek Bailey and that's only a partial roster of what you might glean.

The production and sound here by veteran engineer Phil Brown are nothing short of astonishing—and I don't use that word lightly or often.

Recording at London's Wessex Studios during the eight month long session was to a Studer A800 24 track analog deck at 30 IPS with Dolby SR noise reduction through an SSL (Solid State Logic) board. No EQ was applied to the all tube mike production (you didn't think it got any better than the Studer, right? Among the microphones Brown used were a Telefunken U47 Neumann U48 and M49, which were rented for the sessions.

The drum kit miking consisted of a single Telefunken U47 placed 30 feet away. Once the backing tracks were recorded (said to be a long arduous task including recording single drum hits that were chained together), masters were created using Mitsubishi Digital multitrack recorder (listen, one was used for Jim Anderson's spectacular sounding Patricia Barber albums).

Contributing to the mix elements were five analog recorders producing more than 120 tracks including overdubs of strings, guitars, pianos, and various exotic instruments, electronic and acoustic —all individually recorded and miked from a considerable distance. Some sampling and looping was also used. The mix used a spring echo, an EMT echo plate and a digital delay line.

Engineer Brown's resume is astonishing. He was an assistant engineer at Olympic during the '60s where he worked under (and obviously learned from) Eddie Kramer and Glyn Johns on albums like the first two Traffic albums, Small Faces' classic Ogden's Nut Gone Flake and others. And he worked on Beggar's Banquet, Steve Miller's atmospheric classic Sailor and Electric Ladyland. At Island he worked on Bob Marley albums, Roxy's Manifesto—I could go on!

Surely from that description and Brown's resume your ears can imagine the sonic feast that awaits. The music is dark, atmospheric yet immediate and superbly transparent. That single mike drum kit will float midway between the speakers with eerie verisimilitude. The arrangements drone, creak and wend their way more introspective and jazzy than rock. In fact there's nothing rock-y about any of this.

As a late night communicative listening experience Laughing Stock can't be beat. You'll have trouble understanding the words but for the first few plays you won't care. If you read the lyric sheet you'll find the typeface about as difficult to read as they are to comprehend from listening. On line lyric sites help.

Ba Da Bing is a relatively new reissue label whose head, from what I can gather, is more interested in music than in the purity of the sonics, so here there's no mastering credit, no source listing and the pressing is on 120g vinyl, probably done at Rainbo but the vinyl, at least on the copy I bought, is eerily silent. The album opens with a long stretch of purposeful silence and it's drop-dead quiet. Whether carefully produced or just beginner's luck, this reissue is sonically special—though of course I've not heard the original UK pressing.

Highly adventurous music making, producing and engineering and most highly recommended!