Mute Nostril Agony! Analogue Productions Issues "Strange Days" As a Double 45rpm LP

On college campuses, saddle shoes, cardigan sweaters and khakis were giving way to jeans, T-shirts and sneakers. Crew cuts and neat grooming migrated to long, but still neat hair and extended sideburns. “Hippie chicks” migrated from Haight-Ashbury to college campuses, bringing with them marijuana, mescaline, LSD and yes, the crabs.

Strangers who had shifted sides in the new cultural divide exchanged knowing glances and recognized each other’s slang and “man” filled lingo (as in “hey, man, what’s happening?”). These were “strange days.” Kids who’d tried acid or even smoked pot for the first time that past summer nodded knowingly when they heard the title song for the first time and when they first heard the second song, “People Are Strange,” they just knew Jim Morrison was singing either about their premier psychedelic experience or about a creeping and disturbing sense of alienation from the once comfortable mainstream culture.

Jim Morrison was way ahead of the change: the first album had been recorded in August of 1966 and these songs recorded in the spring of 1967 before the “Summer of Love” were actually mostly leftovers from the first album, but somehow the two albums’ song selection and sequencing were almost telepathically perfect.

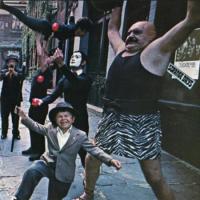

The cover art, photographed by the late Joel Brodsky (he died March 1st 2007 of a heart attack at age 67, which means he was all of 26 when he shot this cover) and best seen by opening this reissue’s gatefold jacket, featured what appeared to be a musician, a pair of acrobats, a juggling mime, a weightlifter and a midget hijacked from a Fellini movie. In fact, none of them were what they appeared to be. In other times the casting might have been seen as inauthentic. In the fall of 1967 when nothing seemed to be what it was represented to be, it was appropriate.

Brodsky was forced to improvise when Jim Morrison refused to pose for the cover. He shot the iconic cover in Sniffen Court a Murray Hill alley near Manhattan’s East 36th Street. The only reference to The Doors can be seen in a poster on the wall behind the weight lifter (who was actually a doorman at The Friar’s Club), over which at a haphazard angle had been pasted a sticker containing the album title. Brodsky’s imagery and especially his use of a muted cool blue color temperature proved more appropriate than would have been any conventional picture of the band.

The musicianship, the arrangement and especially Paul Rothchild’s production and engineer Bruce Botnick’s sonic landscape greatly elevated what had been a jazzy blues/rock band with artistic pretensions to one that had moved forward the art of record production to communicate far more than a document of a band playing in a studio, much as The Beatles had previously done. The album had a unified sonic ambience and backdrop that defined and reflected the time just as did the artwork.

The ominous opener, “Strange Days,” with its unsettling message of uncertainty and of the once solid ground shifting beneath one’s feet, captured both the time generally and the inwardly drawn summer experiences of first time acid droppers and pot smokers specifically. But even those who’d not partaken could easily relate. Rothchild and Botnick’s reverberant production, punctuated by subtle ghostly electronic artifacts and watery, disorienting vocal effects only served to heighten Morrison’s paranoia-soaked lyrics.

Listeners could only gasp with amazement, realizing that what they had been feeling and experiencing for the past few months had been confirmed, was real, and had now been expressed both musically and lyrically. The opener and “You’re Lost Little Girl,” served as a disorienting one-two punch that few first time listeners at the time are likely ever to forget.

“Love Me Two Times” is a simple blues well masked by Ray Manzarek’s baroque harpsichord and the wet, ambient production. Throughout the album, the combination of Manzarek’s hard, choppy keyboards and Robby Krieger’s ghostly, high pitched, echoey, looping guitar lines produce a hard/soft contrast that both soars and slices through the musical firmament, all anchored by Morrison’s powerful vocals.

Audio nerds and musical detectives who liked to explore music’s nooks and crannies could make out some odd edits and “punch-ins” on the opener, but now with better gear and this 45rpm mastering from the original analog master tape, these quirks are laid bare. Listen to the kick drum.

The album has a taunting, fun-house like quality throughout, with the exception of Morrison’s arty 1:30 “Horse Latitudes,” that I remember scaring the crap out of us back then with its images of horses being jettisoned into what felt like dark, cold water. The electronic effects, moaning voices and chilly keyboards produced intense imagery, particularly on Friday nights after we’d brought in from the garage our weed stash and shared a joint (we were very disciplined, smoking only on weekends). Listening now, I’d say the dark, swirling backdrop was produced by slow hand turning of a piece of recorded tape. The side-ender, the liberating “Moonlight Drive,” was a perfect foil for all of the pleasant unpleasantness that preceeded it.

Side two opens with “People Are Strange,” yet another dose of paranoia set to a mid-tempo, Kurt Weill/Bertolt Brecht cabaret-like backdrop (the group had gone from singing “Alabama Song” a Weill/Brecht song on the first album, to writing their own) and continues with two more introspective Morrison musings before concluding with the epic “When the Music’s Over” —the second time the band ended an album with a lengthy declaration. When Morrison proclaimed that “music is your only friend…until the end” a generation listened!

While the band implored in that song “We want the world and we want it now,” Strange Days was not the massive selling album the band had hoped for, though it reached #3 on the Billboard Top 200 and eventually went Platinum. It should have been a huge breakout and why it wasn’t, is difficult to figure, though the dark undercurrents may be the reason. Other than “Moonlight Drive,” the album can be heard as pretty grim—especially by those who’d yet grasped the enormity of the cultural shift that was about to take place. Or perhaps it was the fact that The Doors’ first album was still high on the charts when this one was released.

If the purpose of a vinyl reissue is to either match or surpass the original pressing, this one is a 100% success. I have three supposed “original” gold label Elektra originals. One, mastered at Matrix has the date scribed into the inner groove area: 9-20-1967. The album was released less than a week later. One of the others has “CP-1” on side one and CP-2” on side two. The other has CTH-1/2.

. The one that has always sounded the most open, transparent and “right” to me was the one mastered at Matrix, even though the other two had more bottom end. This reissue cut by Doug Sax from the original master tape under the supervision of Bruce Botnick the original engineer, proves to my ears that the Matrix pressing is the true original because the similarity in tonal balance between that pressing and this double 45 is uncanny.

Except of course that the double 45 offers far greater dynamics, detail and uniformity among the tracks since the cut never extends near the high frequency curtailing inner groove area. So yes, if listen and say “where’s the bass?” on the title cut and some others (though some tracks like “Moonlight Drive” have quite powerful bottom ends) and if you find the top end a bit forward but oh so clean and detailed, rest assured you’re hearing the album as intended.

As on the reissue of the first Doors album the absolute star of this reissue, (especially if you’ve spent 45 years with the originals!) is John Densmore. I promise, you’ve never heard the drums like this, but then you’ve never heard the album like this, period. The faux leather clad box set just doesn’t matter anymore.

As an aside, I once traveled the country in the early 1990s on a promotional tour sponsored by TDK, doing local TV appearances showing people how to transfer their vinyl to cassette (yes it was that long ago!). You can be sure I spent as much time as possible extolling the virtues of vinyl and shitting all over CDs at a time when the propaganda had dulled the collective conscious into thinking CDs were sonically superior and virtually indestructible.

My public relations handler/traveling companion was photographer Joel Brodsky’s daughter Jill. I remember her telling me that though he loved music, he was not a Doors fan. She also kept yelling at me “No tapping!” because I liked to tap to the music as I drove. Stupidly I told that to my wife and now every time I tap in the car, she imitates Jill and yells at me “No tapping!”

While I’m at it, I’ll tell you another “road story.” The final appearance on that tour was on “The Today Show.” Now that was nerve-wracking enough but get this: part of my spiel was to say “When you transfer your records, use a good quality tape like TDK (hold up a tape).” In other words, I was not saying to necessarily use TDK, just that you should use a high quality tape like TDK. That worked for all of the TV stations on which I appeared.

But “The Today Show” back then had far higher standards since it was a production of NBC News. Of course since then, it’s descended into the toilet of product placement and promotions, British Royalty fetish, murder and crime stories and almost no hard news. I can’t watch it anymore.

So, when we ran through the segment with the producer, she said “You cannot mention TDK or hold up that tape. It’s against our standards.” When I was alone with the public relations person afterwards, she said “You must hold up that tape and say “like TDK.” Think of the angel and devil on Tom Hulce’s shoulders in “Animal House” when he was in bed with the drunk townie.

So there I was on the couch, seated between Bryant Gumbel (who could not have been nicer and more welcoming and more intent upon making me comfortable so I would have good appearance) and Debra Norville who was, well hot!

The dissonance in my brain was intense as I thought “Should I hold up the tape and say TDK or should I not?” Now at that time I was working for The Absolute Sound and was not making much money except for this tour, where I was being paid a lot of money by my standards. I was told that even though I’d done a great job (TDK sales tracked up wherever I appeared), my future depended upon my holding up that tape and saying “TDK”. I was so nervous, I can be seen on camera nervously tapping my thighs as the segment began. When I got to the moment where I said “use a high quality tape” my hand involuntarily reached into my pocket and pulled out the tape, which I held up while quickly blurting “like TDK”! If you blinked you missed it, but I did it!

I guess I didn’t tick off NBC because Gumbel asked me to stay on the set so we could come back from the commercial and talk more about vinyl, which we did!

So let’s end this review back on track: if you like the Doors get this double 45 reissue. It’s the best sounding edition you will ever hear and well worth the price, especially if you had any idea what AP's Chad Kassem had to go through to convince the powers that be to let him use the original analog master tapes, and what he had to pay for the privilege.