...but most field recordists of the 1920s and 1930s had enough sense to have their reel-to-reel decks serviced before heading out on the road. Plus, the trendy striped colored LP ruins the retro theme of the project and screws up the sound for no reason.

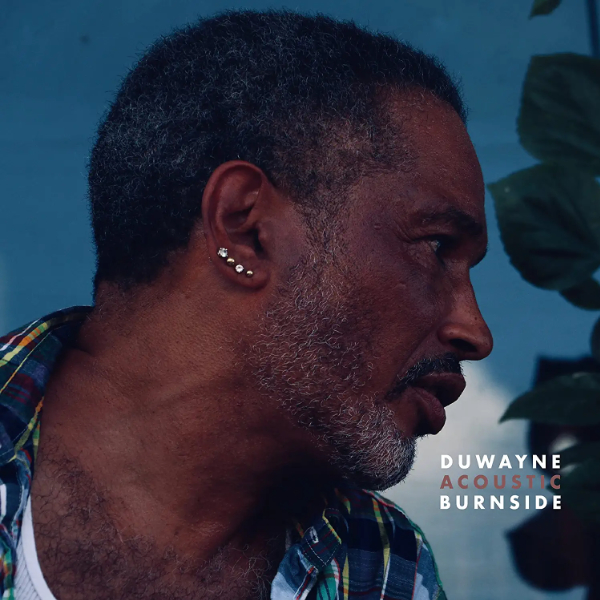

Acoustic Burnside, Duwayne Burnside’s New Acoustic Field Recordings LP, Pays Tribute to His Late Father and to an Era of Simpler Production Aesthetics

A new LP recently arrived in the mail unsolicited — as they sometimes do — but I’m quite glad this one did. Truth be told, when I first took the album out of the package and quickly glanced at the title, Acoustic Burnside, I initially thought it was an archival release by the late, great blues legend, R. L. Burnside. After I dug into playing it, I realized this was something entirely different — and potentially more interesting, at least from an audiophile perspective — as it’s actually a new record from his son Duwayne Burnside, as recorded in the style of his father’s recordings from the 1960s.

Some of you may already know Duwayne Burnside from his work with The North Mississippi Allstars, as he appeared on their albums Polaris (2003), Tate County Hill Country Blues (2003), and Hill Country Revue – Live at Bonnaroo (2004). From the Acoustic Burnside press release, we share the following in italics, in which Burnside details his intentions for doing the album:

“Although I’ve never stopped playing shows, this album is a rebirth for me,” says Burnside. “It puts me in the game again, but it’s perfect, too, because playing stripped down like this, you can hear this music come right out of my heart, because that’s where my daddy put it. He would be proud that I get to honor him this way. And I always remember what he told me about making music: ‘You’ve got to enjoy yourself, and then folks will enjoy you.’ So believe me, there isn’t anything about doing this that I don’t love.”

Now, if Acoustic Burnside were “just another blues album,” it might be less enticing for us to review (and for you to read) because it was simply just another blues album. But Acoustic Burnside is much more than that, as the performances are indeed fine and heartfelt (and I’ll get to all that in a moment).

Acoustic Burnside comes crafted with a special sort of recording pedigree. And for all you purist analog-tape enthusiasts out there, the technical “making of” behind this new album may be of interest in its own right.

To wit: Acoustic Burnside was recorded by Dan Terigo of Dolceola Recordings, with an Ampex 601 and an RCA 77 DX. When I saw those model numbers in the liner notes, I did some instant sleuthing to confirm the former is indeed a vintage portable monaural reel-to-reel recorder, and the latter a classic ribbon microphone that was popular in the 1950s. (Sidenote: a record collector and recording enthusiast contact I’d made some years back showed me some similar mics he owned, which he claimed were used to record Leadbelly back in the day.)

Knowing all this, I was intrigued that Acoustic Burnside might deliver a vintage sound while benefitting from more modern production procedures. From the official press release, again presented here in italics, we now learn about producer/engineer Dan Terigo’s intent:

“We’re a music label focused on analog field recording of American traditional music, with love and adoration for the great field recorders,” he [Terigo] explains. “I love R. L.’s first recordings made in 1968 by George Mitchell and wanted to make a sort of modern version of it with the current generation. So, while Duwayne is renowned for his solid electric guitar playing with influences from modern blues, the musical tradition of his father and his community is rooted very deep in his body and soul, and we wanted to capture that in a more primitive way.”

Opening up the album, I was surprised to find it on color vinyl — clear, with neat purple splatter — which immediately brought the record into present times. Putting the album on my turntable, I gave a pretty wide smile upon hearing that vintage monaural sound coming off a modern release. If you look at the videoclip of Burnside performing “Dust My Broom” below the next paragraph, you can see this was a very simple production, and about as primitive as electrical recording can get — a microphone plugged into the recorder right next to him without any effects, mixers, or other processors.

As some of you know, a good monaural recording can deliver a nice sense of depth and presence, and these field recordings on Acoustic Burnside capture that essence. Just go to the last track on Side One for that above-noted cover of Elmore James’ “Dust My Broom,” and listen for not only Burnside’s great performance, but also the sounds of the kids in the general area playing and screaming. It sounds like there might have been a park nearby, maybe across the street. You can also hear a bird tweeting, and more, in the distance. It’s pretty neat!

Overall, the guitars are generally very up front in the “mix” (if you will), and yet there is that sweet ambient sensibility from the spaces in which Burnside was performing. Junior Kimbrough’s “Stay All Night” is a driving, almost funky workout. Duwayne’s own songs are pretty great here as well. I love the sort of Hendrix-meets-SRV-flavored “She Threw My Clothes Out,” which I could totally hear blown out into a full-on electric band. But it works just great here unplugged, with some ripping, fluid Burnside soloing. “Bad Bad Pain” is another original Duwayne Burnside ripper that could easily rock out but works well on solo acoustic guitar — again, especially when he lets loose on a solo.

Inherent imperfections are part of the charm of any field recording, of course, and this album is no exception. At certain points, I detected a telltale warble that can happen to older reel recorders that might need servicing — or at least a good head cleaning and demagnetizing.

Don’t be surprised if you hear some fairly audible wow and flutter, with an emphasis on the flutter. Again, while I don’t know for sure, I am assuming this was a tape-recorder maintenance issue. I used to encounter similar warbles on recordings made on my beloved 1990s Tascam 8-channel cassette multitrack if the heads got dirty, needed to be demagnetized, and/or if the tape was wearing out from too many takes.

Fear not — the flutter is not present on every track here, so don’t despair if you are a fan of pure pristine presentation. Much of Acoustic Burnside sounds quite good, all things considered. Despite these periodic imperfections, somehow Acoustic Burnside feels just right, this raw sensibility warming up an otherwise crisp and fresh modern blues album.

Oddly enough, perhaps my bigger issue with Acoustic Burnside is not the recording, but the color vinyl pressing. It looks pretty, don’t get me wrong, and it sounds overall quite nice — it is well-centered, and all that. But because of this particular style of color vinyl — clear, with color splatters — you can hear in the far background a sort of slightly whoosh/fluttery sound. It’s not really noticeable during the songs — but between tracks, I could hear it.

So is that a dealbreaker, you ask? Not for me, ultimately. Taking the mile-high view, I’m genuinely glad Burnside got to make this album and see it released in a broad manner. And if the color vinyl appeals to a younger audience just discovering the blues and who also might be “into” this sort of pressing, so be it! In that sense, I’m all for giving the people what they want — if I might borrow a phrase from marketing textbooks and an early-1980s Kinks album! [Yes, you may!—MM]

I would assume (and hope!) at some point, the album will be made available on standard black vinyl, so keep an eye out for that possibility. Until then, check out the purchase options underneath my bio, and see if Acoustic Burnside might become one of your favorite unplugged jams of the year.

(Mark Smotroff is an avid vinyl collector who has also worked in marketing communications for decades. He has reviewed music for AudiophileReview.com, among others, and you can see more of his impressive C.V. at LinkedIn.)

[MM notes: If you look around, you should be able to pre-order a copy of Acoustic Burnside for $22.49, though we have seen it listed elsewhere for as much as $29.99 (and up, elsewhere). You can check out some of the purchase options here, as a starting point. The release date is September 23.]

DUWANYE BURNSIDE

ACOUSTIC BURNSIDE

1LP (Dolceola Recordings)

Side 1

1. Going Down South

2. See My Jumper Hanging on the Line

3. Poor Black Mattie

4. She Threw My Clothes Out

5. Alice Mae

6. Dust My Broom

Side 2

1. Meet Me in the City

2. Stay All Night

3. She Threw My Clothes Out (Alternative Take)

4. 44 Pistol

5. Bad Bad Pain

6. Lord Have Mercy On Me

- Log in or register to post comments

if played on a "retro" suitcase "vinyls" player those sonic imperfections would be masked by lots more wow & flutter.

I had no idea that "field recordists (sic) of the 1920s and 1930s" had reel to reel recorders.

Oh, wait. They didn't.

Sheesh.

...have reel to reel recorders in the 1920s and 1930s, they just used wire instead of tape. Of course, many of these were made direct to 78 rpm disc.

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/recordist

re·cord·ist | \ ri-ˈkȯr-dist \

Definition of recordist

: one who records sound (as on magnetic tape)

...to want to be right at all times, particularly in a public forum such as this, but I would urge you to consider at least the possibility that your observation was flawed rather than altering course to include wire recordings. You know perfectly well (I assume) that commercially available recordings from the era you cite mainly used acoustically-, and later electrically-recorded 78rpm parts with no intervening tape, wire or other steps. Wire recorders were pretty poor at the time. If you're aware of how they could be serviced prior to each use you're way ahead of me - I've never used one.

Regarding my gentle criticism of your etymology - no offense was intended and I hope you'll accept my apology if any was given. I was merely pointing out that a 'recordist' was barely a thing 100 years ago -- folks involved in making records were called engineers. They were also called thieves for the way they treated artists but of course that's another story for another time!

My nomenclature was acceptable, but my dates were off due to haste in posting. Thanks for pointing it out, and I apologize if you were bothered by this.

In retrospect, my real point is that someone pretending to make an authentic old-fashioned reel-to-reel field recording in THIS day and age should have made sure their equipment was in good shape before proceeding. And black vinyl would be much more appropriate.

Felicitations, TL.

Nobody needs to waste the price of a pizza and a beer on this (seemingly) poorly-executed record.

I really like pizza and beer.