Analog Corner #111

I recently canceled my daily subscription to the New York Times and took one for the Wall Street Journal. I find the Journal's political coverage, unlike that of the Times (or Fox News), to be "fair and balanced," and I read the WSJ's editorial page as I do The Onion: for amusement only.

The Journal's "tech" columnist, Walter Mossberg, does a thorough job of covering his beat—except when it comes to audio gear. There he leaves a gaping hole: he doesn't discuss sound quality. In this, he's not so much alone among mainstream tech writers as probably among the majority. But find me a camera writer who doesn't get around to mentioning whether the camera takes a good picture, or who doesn't think picture quality matters.

In late July, Mossberg covered Apple's new Airport Express. The device is basically a plug-in WiFi range-extender with a built-in D/A converter so you can run cables from it to an audio system or radio with an auxiliary input, and stream iTunes content from your remote computer. I noted that Mossberg had failed to mention sound quality and dropped the issue from my mind.

That afternoon, Stereophile writer Barry Willis cc'd me a letter he'd sent Mossberg, along with Mossberg's response. Willis gently chided Mossberg about his neglect of the sound, and Mossberg responded with a pleasant letter explaining that he's not an "audiophile," how "subjective" it would be to mention sound quality, and how his "general interest" readers are "happy [to listen] through cheap speakers." He also let on that, listening through computer speakers, he can rarely hear any difference between a CD and a 128kbps MP3 copy of it.

That incited me to send Mossberg this:

Walter: I got cc'd a copy of your response to my fellow Stereophile writer. I find your response really frustrating.I wish I could publish Mossberg's reply in its entirety here, but when for reasons of legality and common courtesy I asked for permission, he made it clear that he considered our exchange "personal" and refused. Having had some obviously private e-mails made public by an online psycho-imbecile, I understand completely. However, the opening line of Mossberg's response, "Spoken like a true snob," deserves airing. Admittedly, my letter baited him, but the "snob" accusation floored me. Since when does "better" mean "snob"? This reminds me of people who take shots at John Kerry because he reads.It's kind of like "I'm happy with crap, most of my readers are happy with crap, and there's no point in clueing them into anything better."

Your readers are not poor. They are not into crap in other areas of their lives. I promise they don't drive crappy cars, they don't eat crappy meals, they don't wear crappy clothes, they don't have crappy kitchen appliances and crappy bathroom fixtures, and they don't drink crappy wine.

And I doubt the writers at the WSJ who cover those subjects write about the low end of those products, or don't attempt to help readers to upgrade their experiences.

I read the WSJ. Its cultural and consumer coverage is not about crap. It is inevitably about quality.

One does not need to be an oenophile to know a good wine from a crappy one. One need not be a gourmet to know the difference between a fine meal and one from McDonald's.

Your answer about not being an "audiophile," and not hearing the difference between a CD and an MP3 played back on a computer, strikes me as a cop-out.

One of the reasons your readers are "happy" playing back crappy-sounding MP3s on crappy-sounding computer speakers is because many of them don't know that anything better is possible. Why? Because, to a degree, they rely upon you! And you just don't seem to be interested.

I guarantee you, you'd easily be able to distinguish a quality listening experience from a computer-driven MP3 one.

You are in a position to both improve the quality of your listening experience and then pass that possibility on to your readers so they can pursue something better when listening to their favorite music—and this has nothing to do with being "an audiophile," whatever that is.

The pursuit of gadgets and gizmos is fine, but without at least an expression of the quality of the experience, such a pursuit is empty and useless. It leaves the reader to play with gadgets instead of pursuing a quality experience.

The gizmo is the means to an end, not the end...(I know, audiophiles get accused of that, too).

It is like a wine writer only writing about $5 bottles. Now there's nothing wrong with $5 bottles. I've found some great ones. But I know that a $5 bottle is not a good $50 or $100 vintage bottle, and most anyone can taste the difference.

Yes, you write for a "general" audience, but for some reason, when it comes to virtually every other pursuit in the WSJ, travel writers don't recommend Best Western, food writers don't recommend McDonald's, wine writers don't savor Midnight Express, and automobile writers are more likely to cover BMW instead of Kia.

Why? Not because your readers are "gourmets" or "oenophiles" or "racing drivers," but because they are well-heeled, sophisticated, educated, and want the good things in life—and, when exposed to them, can easily appreciate and discern the differences between what's good and what's crap.

The only subject where this doesn't seem to hold true is audio, where mainstream writers are content with a crappy, plastic listening experience and have convinced themselves that their readers are as well, even though in every other subject you can name, this is not the case.

I don't understand this, never have and never will.

Please pardon my tone...I am frustrated. When I bring music-loving neighbors and friends over to hear my audio system—and these are not "audiophiles" but "general readership" people—they inevitably say the same thing, which is, "My God. I've never heard anything like that! It's wonderful. I didn't know music could sound like that! Why didn't I know about this?"

And the answer is? The answer you gave Barry Willis! The readers are happy listening on crap. Well, I don't buy it. They're happy listening on crap because that's all they know. A small part of your job, it seems to me, is to let them know there's better.

The rest of Mossberg's letter indicated a deep-seated prejudice about who "audiophiles" might be. As an audiophile, I found it as insulting as I might have had he found out I was African-American and his first suggestion was that I get off welfare and get a job.

Mossberg felt it necessary to extol the virtues of the Apple iPod to me, concluding that everyone but a few "audio snobs" find the sound "excellent." As a longtime iPod owner, I hardly needed to be told that. No doubt he'd be shocked to discover that I, too, listen to music on my computer and actually enjoy the experience, or that I enthusiastically review inexpensive A/V gear in other venues.

In his response, Mossberg accused me of seeming to want him to go on a "crusade" to get people to "dislike" the music they like, played back the way they like it: on computers through plastic speakers. Most of his readers, he assured me, "love—love" listening that way. I'd bet that most of them also compute on a Windows-based computer, so why cover Apple products—which are also accused of appealing to "snobs"? (Hey! Maybe that's why I'm an Apple guy!)

Even though, in my wine analogy, I admitted to liking, finding, and drinking inexpensive wines, and acknowledged that the WSJ's wine writers cover such wines, Mossberg felt it necessary to "oh, and by the way" me that the wine writers "regularly review inexpensive wines." I guess I need to "oh, and by the way" him that they cover the expensive ones too, and do so without being accused of being on a "crusade" to get people to "dislike" inexpensive wines.

I didn't do that, but I did write back to explain that I'm an iPod fan and not a snob, and that when I review inexpensive gear, I find that some of it sounds surprisingly good, some of it sounds like crap, and what's wrong with telling people which is which, and not just which has the best navigation system? The Consumer Electronics Association has invited me to run a panel discussion at the Consumer Electronics Show in January about why audio is in the crapper. You've just read the first piece of evidence I plan to submit.

More phono preamplifiers

There are more choices in outboard phono preamps today than there have ever been, and they're lining up here like planes waiting to take off from Newark/Liberty. Keep in mind that the hundreds of phono preamps I've already reviewed are no longer in my possession and so weren't available for me to use them in direct comparisons. What follows is nothing more than a snapshot in time.

LPs used were John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman (Impulse! AS-40, original pressing and Speakers Corner reissue), the superb-sounding four-LP boxed set of Bob Dylan's Live 1964: Concert at Philharmonic Hall (Columbia/Legacy/Classic Records C2K 86882), Mobile Fidelity's near-miraculous twofer of Alison Krauss & Union Station's so long so wrong (MFSL 2-276), and John Lill's recital of solo piano music by Schumann, engineered by Tony Faulkner (Greenpro 4001/02). Someone I used to think was a friend is going around saying that I listen to the same three records over and over. In an exercise such as this, it's the only responsible thing to do.

NAD PP-2 ($129)

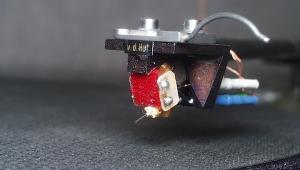

This upgrade of the PP-1 adds greater gain and MC compatibility. NAD claims to have improved the circuit-board layout and increased parts quality; metal-film resistors and film-type capacitors are now used. The power-supply voltage has been upped from 15 to 24V, which NAD says improves overload margins and dynamic capabilities. The wall-wart–powered PP-2 has separate switchable moving-magnet (MM) and moving-coil (MC) inputs and a single set of outputs. MC gain is fixed at 60dB loaded at 100 ohms + 180pF, while the MM offers 35dB of gain at 47k ohms + 220pF. The input sensitivities for 200mV output are 0.2mV and 3.5mV, respectively. The MC and MM signal/noise ratios (A-weighted with cartridge) are 79dB and 80dB, respectively; unweighted, they're 73dB and 70dB. Distortion is 0.03%, while the RIAA accuracy is ±0.3dB.

This tiny, 1-lb box surprised the hell out of me, both for its quiet and for the sound it made. I routinely fooled listeners into thinking they were hearing one of the two more expensive phono preamps in this mini-survey. That's how good the PP-2 was at doing what it did well and hiding what it didn't.

The PP-2 had no problem handling the Graham Nightingale cartridge's 0.45mV output, delivering a relaxed, surprisingly rich-sounding picture that placed solid, three-dimensional images on a believable soundstage of modest size—and that was through the very revealing mbl 101E loudspeakers (reviewed elsewhere in this issue). Somewhat dry, less than generous on harmonic overtones, and lacking overall complexity and dynamic subtlety, the PP-2 still managed to get the fundamentals remarkably correct—including the bass, which was pleasantly well-extended and satisfyingly tactile, if somewhat indistinct. The overall picture was very well-organized and solid, the physicality coming at the expense of high-frequency extension, air, and bloom—but that's preferable to grain and hash, both of which the PP-2 lacked.

The combination of the PP-2 and Sumiko's new Evo III Blue Point Special phono cartridge (2.5mV output, $349) provided genuine musical satisfaction for under $500. Yes, the $750 Gram Slee Gold Era took the music to another level of harmonic and dynamic refinement, and especially of liquidity and flow. But the inexpensive NAD-Sumiko combo was mellow, almost golden, and not at all objectionable when forced to perform in front of $23,000 power amps and the $45,000/pair mbls.

The NAD PP-2's combination of background quiet, image solidity, soundstage organization, and freedom from obvious flaws of commission made it a pleasant surprise. It's a sleeper.

Parasound Z-Series ($150)

This MM/MC preamp features an internal power supply fed via an IEC AC jack. The 3-lb, rack-mountable chassis includes an AC polarity switch in order to provide hum-free performance when used in a complex home theater system, which was one of Parasound's goals for the design. Apparently, they've heard from custom installers about the vinyl groundswell.

The specs provided by Parasound are scattershot: input sensitivity is rated at 0.15mV–2V without regard to MM or MC input, no gain spec is listed for either input, and the input impedance is 47k ohms (for both MM and MC inputs, I assume). The S/N ratio is 75dB, referenced to a high 5mV input, which gives you a clue as to the Z-Series' one major fault: it was a bit noisy in MC mode, even with the Graham Nightingale cartridge's relatively ample 0.45mV output. While the Z-Series somewhat bettered the PP-2's MM performance, I'd go for the smaller, less expensive NAD if I were looking for a cheap MC preamp.

That said, in MM mode the Z-Series made an impressive showing for a budget-priced phono preamp: similar to the NAD PP-2's overall performance, but with a bit more extension, air, and sparkle on top. As with the PP-2, the most impressive aspect of the Z-Series' sound was what wasn't there: grain, sizzle, edge, and grit. The Parasound's sins, too, were of omission, particularly in terms of midband "bloom." The Z-Series produced somewhat sharp edges compared to far more expensive phono preamps, but without any annoying etch—the overall picture had a pleasing clarity and rhythmic organization. Cymbals rang cleanly and with more metallic edge than through the PP-2, and overall, there was more "air." The Z-Series' soundstage was ample, if not expansive.

Overall, this level of performance used to cost far more than $150. Each of these inexpensive phono preamps approximates, more closely than not, the sound of the original Lehmann Black Cube ($595). I'm not suggesting they're as good, especially in terms of dynamics, and they certainly aren't as configurable—but they delivered the essence of what caused such a big buzz among analog loving audiophiles when the Cube first appeared.

Krell Reference KPE ($2200)

The KPE MC phono preamp (footnote 1) is available as a standalone unit with power supply for $2200, or as a $1600 add-on when used with and powered by Krell's KBL, KCR-2, or KCT preamplifiers. I auditioned the standalone version. Krell also offers a standard KPE, configurable for MM or MC. The MC-only Reference has better parts, more flexibility in configuration, a greater S/N ratio (80dB ref. 0.5mV input vs 71dB), and almost 12dB of additional gain (58–76dB in 6dB increments vs 64.5dB).

If you like running your low-output MC at 47k ohms, forget the KPE. But with the KPE, you wouldn't want to anyway—it's one of those phono preamps whose suggested loading seems to work best. For instance, Transfiguration cartridges (including Graham's Nightingale) sounded best at the suggested loading of 100 ohms. Also, matching gain to cartridge output is critical. The KPE didn't sound overloaded when set to 76dB of gain, nor was there any noise to speak of—but when I reduced the gain to 58dB or 64dB, the sound became far more relaxed and tactile while remaining both super-detailed and dynamic.

Switching from one of the inexpensive phono preamps shocked my system with the improvements wrought by the Krell. I suddenly heard the stretched skin of the banjo on the Alison Krauss disc, the profusion of colors emanating from McCoy Tyner's piano and the honey in Hartman's voice on the Coltrane album. Cymbals went from crunch to shimmer, and the dynamics and soundstaging opened up and bloomed even as the focus improved. (Even so, the NAD and Parasound designers have earned my greater respect for just how much they've managed to accomplish on a tight budget.)

The KPE is only the second Krell component I've reviewed. As with the company's Standard SACD player, the KPE's performance ran counter to the cliché about Krell gear sounding bright and hard. Yes, the KPE could sound that way if I maxed out the gain running one of today's highish low-output MCs, such as the Nightingale, or if I ran it at 1k ohm instead of the recommended 100 ohms. But when the KPE was broken-in, and with its gain and loading optimized, its sound was hardly bright. Still, it was on the crystalline and upfront side of neutral, somewhat at the expense of body and three-dimensionality.

The KPE's extremely low noise floor allowed the music to "pop" from jet-black backgrounds and contributed to dramatically enhanced microdynamics compared to the budget preamps. All of this brought John Lill's Schumann disc convincingly to life. While neither "bright" nor "hard," the overall sound emphasized transient attack over the resulting aftermath—and that was true throughout the sonic spectrum. Bass was tight, well-extended, and "fast," trebles were clean and effervescent. Any sort of tubelike midband "bloom" was missing in action, but that's to be expected.

The result was a very exciting and immediate sound with lots of air and detail, though with a cartridge equally as "fast" as the KPE you might get the sense that the Krell wasn't savoring a musical thought long enough before moving on to the next. Koetsu's cartridges might be better matches for the KPE than the Graham Nightingale. The combo of KPE and Lyra Titan was nearly ideal, the KPE's speed and attack nicely balancing the Titan's rich bottom end.

Overall, the Krell Reference KPE is a competent, nicely built phono preamp that offers very credible performance—especially dynamically—for the price, as well as outstanding configurability. But it's been around for a while, and I don't think Krell's put much effort into the subject of phono stage design in some time.

Ayre P-5x ($2350)

Billed as an improvement over the phono board available as an option on Ayre's K-1x preamp, the P-5x is a zero-feedback, FET-based, MM/MC phono preamp offering three levels of gain (50dB, 60dB, 70dB), selectable via jumpers mounted on its circuit board. Using the balanced XLR inputs adds 6dB of gain to each setting. DIP switches mounted on the rear panel grant access to minimal but well-chosen loading points: 100 ohms, 1k ohm, and 47k ohms. Tweakers need not fret: Because there are two sets of inputs (one balanced, one single-ended), the unused set can be used for custom loading with the resistors of your choice. Ayre provides detailed instructions on how to do this.

Physically and sonically, the P-5x is vintage Ayre. Outside is Ayre's usual attractive brushed-aluminum chassis, while inside is a single circuit board, cleanly and symmetrically laid out. If you need to change the default gain of 60dB, you'll need to remove 10 hex-head screws. I found that setting the correct gain worked for all but the lowest-output MCs. Ayre claims that the balanced input yields the best sound. I do have a balanced set of Cardas Neutral Reference DIN-to-XLR cables, but during the review period I had the Kuzma Air Line and VPI JMW tonearms in the system, neither of which features a DIN connector. I used the Ayre's single-ended inputs.

Like the Krell Reference KPE, after a long break-in period the P-5x provided dead-quiet, jet-black backgrounds and outstanding microdynamic shadings—but its sound was quite different. The P-5x was not nearly as "fast" and upfront as the KPE, instead painting a somewhat warmer and richer picture, with greater image solidity and three-dimensionality. The tradeoff was a bit less air and "shimmer" on top, which resulted in less immediacy and initial excitement, but greater listening satisfaction over the long term. The Ayre was also somewhat drier and less liquid than the Krell, but ultimately more neutral, and seemingly more transparent—the transient attack didn't seem to shout out and intrude on every musical event.

As with the Krell, the Ayre's loading, and especially its gain, had a profound effect on the final sound. Given the FETs' inherently low noise, the less gain you can get away with, the more nuanced, neutral, and refined the final sound will be. Find the gain "sweet spot" and you won't lose dynamics, either. Also as with the Krell, the Ayre's resolution of low-level detail was noteworthy, as was its overall dynamic presentation. The Ayre "floated" the picture in three dimensions with greater ease, allowing me to hear farther into the soundstage. Where the Ayre was most different from the Krell was in the bass: while not quite as taut as the KPE's, the P-5x's bass had equally good extension while adding an almost tubelike richness and texture.

Overall, the P-5x is not a radical departure from Ayre's "house sound." Rather, it's a refinement that offers a richer sonic palette than the phono card built into the K-1x preamplifier (as I remember it), with improved three-dimensionality and body, greater bass texture, and a smoother sound overall, with less noticeable dryness. Tubes will get you more liquidity, delicacy, and bloom, but at the expense of neutrality and bottom-end solidity. When properly configured and broken-in, and used with an appropriately voiced cartridge, the P-5x lets you forget it's even there—about as high a compliment as can be paid a piece of audio gear in the service of music. I'll stick with the $7k Manley Steelhead, however.

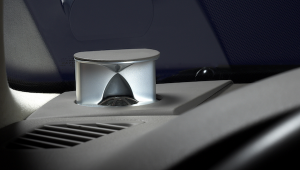

Expressimo Audio Micro-Tech digital stylus force gauge ($160)

This low-cost stylus-force gauge— www.expressimoaudio.com/gauge/gauge.html—can measure 0.1gm to 120gm in increments of 0.1gm. It places the stylus very close to the record surface to measure the tracking force with greater accuracy, it's easily self-calibrated, and it appears to be bulletproof. When referenced to a 2gm laboratory-grade weight, its digital readout always displayed precisely "2.0." The Micro-Tech proved as accurate as and far less delicate than the Winds gauge, which cost $800 when I reviewed it in the January 1997 issue.

Footnote 1: The basic KPE was reviewed for Stereophile by Martin Colloms in June 1994, the KPE Reference by Wes Phillips in June 1997.—Ed.

Sidebar: In Heavy Rotation

1) Bill Berry, Shortcake, Audiophile Master Records 180gm LPs (2)

2) Dolly Varden, The Dumbest Magnets, Diverse Records 180gm LP

3) Jimmy D. Lane with Double Trouble, It's Time, Analogue Productions Originals 180gm, 45rpm LPs (2)

4) Nat King Cole, Just One of Those Things, S&P Records 180gm LP

5) Norah Jones, Feels Like Home, Classic 180gm LP

6) Begoña Olavide, Salterio, M!SA Recordings 180gm LP

7) Hank Mobley, Soul Station, Classic Records 180gm mono LP

8) Ben Webster With Strings, Sophisticated Lady, Speakers Corner 180gm mono LP

9) Various Artists, Power of Soul: a Tribute to Jimi Hendrix, Classic Records 180gm LPs (2)

10) Thomas Dolby, Forty-live Anniversary, Salz 014LP 150gm LP