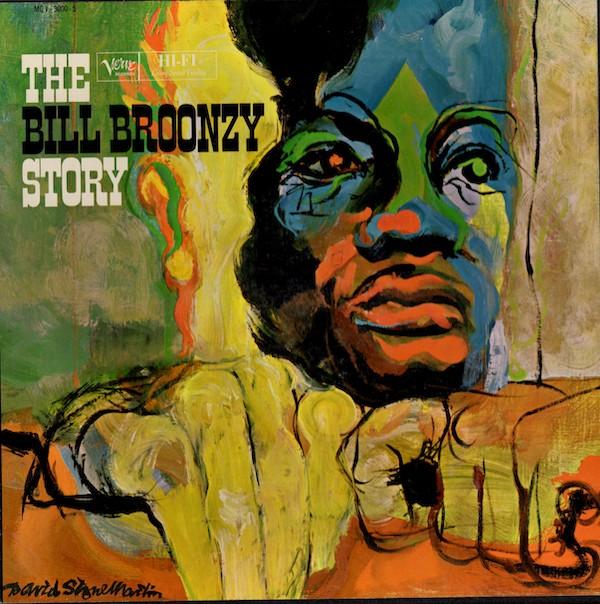

Big Bill Broonzy--- The Bill Broonzy Story Verve MGV 3000-5--- The Records You Didn’t Know You Needed #11

The session was organized and paid for by Bill Randle (1923-2004), a former disc jockey and a man of great and varied accomplishments. He had hosted from 1945 to 1949, in his native Detroit, “The Interracial Goodwill Hour”, one of the first R&B radio programs to be hosted by a white man. In Cleveland, in 1953, he promoted the city’s first concert featuring both black and white artists. In the mid-50s, Time magazine and Downbeat both proclaimed him to be one of the country’s top DJs. In January 1956, Randle introduced Elvis Presley to a nationwide TV audience on The Dorsey Brothers’ Stage Show. Randle was eventually to earn a B.A., a doctorate, a law degree, and three masters degrees.

In 1957, Randle was in a graduate sociology program concentrating on, “the impact of urban milieus on rural folkways” and decided to do an in-depth study of Bill Broonzy. His interest in Broonzy was not entirely academic. He believed that he was the greatest blues singer and was later to say, “I guess I developed what you would call a cultural guilt complex. And also, I had the money. So, I decided that I would just do some things that I thought should be done. And one of them was to record Big Bill Broonzy.”

Randle knew that Broonzy was very ill, and in his foreword to The Bill Broonzy Story he wrote, “My prime motive for recording Bill Broonzy was to preserve as much of the blues complex as he was able to give us” and “get as much of his life and music on tape as was possible.” His intention was not to make a commercial record, but instead an academic field research document. Randle’s only plan for the recording sessions was to let Broonzy talk about his life and play music.

Randle hired Studs Terkel, radio personality, oral historian, and a friend of Broonzy who had worked with him in a touring folk song review, to act as the interviewer. Terkel understood the history of the blues, their importance in black American culture, and his sympathetic presence set Broonzy at ease. In fact, Terkel had done an interview with Broonzy on his radio program four years before which Randle had probably heard and The Bill Broonzy Story sessions are a more in-depth version of that conversation.

The three sessions produced slightly less than ten hours of exceptional playing and singing and lots of talk by Broonzy some of it moving, some of it humorous. Broonzy was a great storyteller with an honest, truth-telling voice, but since he had become a “folk blues” singer, his stories had become less history than art, entertainment, and education, and much of what he told Terkel and Randle at the Story sessions was “true” but not factual. Randle failed in sociological documentation but succeeded in recording an artistic performance that was emotionally true.

Broonzy was born as Lee Conly (or “Conley”) Bradley on June 26, 1903, in Vaugine Township, Arkansas. After the late 1930s, when his “folk-blues” career began, Broonzy claimed repeatedly to have been born in 1893 in Scott Mississippi. Bob Riesman’s excellent biography of Broonzy, “I Feel So Good” establishes beyond doubt, from family records, that he was not telling the truth.

In the early 1920s, probably sometime in 1922, Broonzy moved to Chicago where he made his home for most of the rest of his life. In 1925, he bought a guitar and began playing. He had played fiddle for dances in Arkansas but the guitar was a much better choice to play the urban dance music that was popular in Chicago.

In late 1927 or early 1928, Broonzy made his first record. It sold well enough to warrant the record company calling him back for a follow-up, and he became one of the most successful blues artists before World War 2. Broonzy was a supremely skilled and versatile guitarist with a warm soulful voice and clear diction, a distinct asset for working in noisy clubs and for jukebox play. Most importantly, he was a gifted songwriter that could come up with slow blues or uptempo dance tunes with memorable, frequently suggestive, lyrics, seemingly at will. By the end of 1943, he had recorded approximately 260 songs under his own name and probably an equal number as a guitar playing sideman.

Broonzy became a popular performer in bars, clubs, and theaters in the black neighborhoods of Chicago and other cities. In 1937, he began playing with small bands that included horns and drums and his records featured a more pronounced and swinging dance beat that presaged the post-war Chicago blues sound. His records were staples on the jukeboxes of taverns catering to Blacks. A 1941 listing of records on a Mississippi jukebox included two Broonzy records. “Big Bill” was now well known, if not famous in Black America, but completely unknown to white America.

This was to change on December 23, 1938, when Broonzy appeared at Carnegie Hall as part of the “From Spirituals to Swing” concert organized by John Hammond as a celebration of African-American music from its origins to the present. The concept of presenting a program of Black musicians in America’s foremost concert hall before an integrated audience was a daring one. Hammond was at the forefront of the fight against segregation and had helped and encouraged Benny Goodman to make his, the first integrated band. The sponsors of the concert were the Theatre Arts Committee, a left-wing organization, and “New Masses”, a Marxist magazine with ties to the Communist Party. The concert was more than a sellout, and chairs had to be placed on the stage to accommodate the overflow. It was an arty, intellectual, leftist audience with many members of the media and movers and shakers in the music world, including Alan Lomax, in attendance.

Hammond had wanted to present Robert Johnson, already a mysterious and legendary figure, as the exemplar of “primitive blues.” When Hammond learned that Johnson was dead (he died on August 16, 1938), he contacted Vocalion records for suggestions of a replacement, and Blind Boy Fuller, their most popular blues artist, was recommended. Investigation showed that Fuller was in jail for attempting to shoot his girlfriend and Hammond booked Vocalion’s next best-selling blues artist—Broonzy.

At the concert, Broonzy performed “It Was Just A Dream,” a humorous piece with a bit of biting social commentary. “I dreamed I was in the White House, sittin’ in the President’s chair. I dreamed he shake my hand said…Bill I’m glad you’re here, but that was just a dream. Lord, a dream I had on my mind. And when I woke up not a chair could I find.” Broonzy was a seasoned professional who could size up an audience, and he had made a wise song choice. On the recording of the concert (Vanguard Records), the near all white audience can be heard laughing throughout and roaring approval at the conclusion. Broonzy had found a new audience and the white audience had found Big Bill Broonzy.