Analog Corner #27

(Originally published in Stereophile, October 12th, 1997)

I heard this story from a manufacturer whose car broke down somewhere in a rundown Queens neighborhood one afternoon: He went into a bodega to make a phone call and struck up a conversation with the owner. Their talk led to audio, then to a trip to the basement of the former record store, where thousands of Living Stereos and other audiophile treasures had been sitting for decades, gathering dust and value. The manufacturer would visit each week and walk out with a few hundred unplayed gems, for which he'd pay a few bucks each.

True story? Audiophile wet dream? Who knows? Who cares? We love this stuff. So when I got a call from Rick Flynn (proprietor of Quality Vinyl, a mail-order, audiophile-oriented record dealer) about 650,000 records—every one of them stone-cold mint—locked in a warehouse in York, Pennsylvania since 1973, and would I like to have a look...I bit.

To York, you dork

The two-and-a-half-hour springtime drive to York was pleasant enough; I passed Dorney Park Amusement Center and skirted temptingly close to a literal drive up the Hershey Highway. But with visions of 650,000 LPs dancing in my head, I passed on the sweets and made my way to York. Flynn hadn't filled me in on the details. I had no idea why 650,000 records were in a warehouse in York, or who owned them.

When I pulled up to the '60s-style building, located in a semi-rural area strip-zoned for industrial growth, I felt as if I'd entered a time warp: Weeds were eating away at the foundation of the giant, one-floor warehouse, and sprouting up through cracks in the parking lot's asphalt. I walked through the open front door. The placed looked and smelled as if no one had been there for years. I heard voices, followed them past a rack of ancient, cobweb-encrusted tape-duplication machinery, and found myself in an office.

The last time I'd been in an office like this had been in 1973. It was a place called Music Merchants in Woburn, Massachusetts, a record "one-stop" owned by the late Howie Ring, who also owned New England Music City and Cheap Thrills, a chain of Boston-area record stores for which I created radio commercials that announced new releases while politically satirizing Watergate, the war in Vietnam, and the likes of Anita Bryant and Jesse Helms. Ring was thrown from his Mercedes in a traffic accident. No seatbelt.

Anyway, this office had the same shag rug, the same orange-and-brown "earth tone" decorating scheme, the same wood-paneled walls, the same all-mechanical office equipment. There wasn't a computer in sight. You could almost smell the cigar of the balding, rotund, bespectacled accountant who must have operated the forbidding-looking adding machine in the adjoining room. What a memory rush!

In the office were Rick Flynn and the man whose office it was: Sig Friedman, a well-maintained, late-50s–looking kind of guy, and president and founder of RCOA, The Record Club of America. Remember RCOA? Well, the Club has been inactive since 1973, but it still has inventory: those 650,000 mint unplayed LPs, the last of which entered the warehouse in the early '70s. You know what that means: not a single "digitally remastered for better sound" record among them.

Friedman, a lifelong record fanatic, attended Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island during the late 1950s. Very few record stores at the time had "deep" catalog, and none of them were in Providence. So Friedman made weekly trips to Boston for his vinyl fix. Friends would ask him to pick up records for them. It got so big, he began buying from distributors and turning it into a little side business. Soon he was posting flyers at colleges all over New England offering any record in the Schwann catalog. Kids bit.

That graduated into campus reps handling the business. Friedman would batch the orders and every few weeks visit Boston, where not only Capitol, Columbia, and Decca had factory branches, but also where large, independent distributors like Music Suppliers of New England would fill the more esoteric requests. When Friedman was drafted,his brother filled in, in what was still a very small business.

When Friedman got his discharge he began growing the business, using direct mail—unusual and innovative at the time—to add membership to his "record club." Soon he began advertising in magazines, eventually building up a business that, by 1972, did a total of almost $30 million, with a pre-tax profit of almost $3 million. Three mil in 1972 dollars? Not bad for an individually owned business, eh?

Show us the money!

The huge cash flow thrown off by the business allowed Friedman to buy 60 acres of prime real estate in York, then a pretty sleepy place, and build his warehouse, which he owned outright—it never had a mortgage. Life was sweet. Meanwhile, executives at the major labels who'd signed licensing deals with RCOA were watching this little pitzela rake in the cash. The majors decided they could do record clubs too. And they did, cutting off RCOA. RCOA declared bankruptcy in 1974 and sued the labels for breach of contract. It was, according to Friedman, "the longest successful Chapter 11 proceedings in modern American bankruptcy law, lasting nine years."

According to Friedman, RCOA won a number of the suits, and ended up settling some others for "very substantial amounts, plus interest." Friedman leased the warehouse space out to a direct marketer and made even more money that way. Meanwhile, the 650,000-record inventory sat while the protracted litigation was settled. By the early '80s the compact disc was starting to happen, and Friedman figured the records were worth more as landfill than as anything else. Luckily no swamps near York needed filling, and Friedman had no incentive to do anything with the vinyl but let it sit.

About a year ago, Friedman started doing some research: Records were coming back. Records were collectible. "I never dreamed Mercury Living Presence records would have value," he told me. "I was shocked." The 650,000 records comprise about 8500 different titles, with about 3000 titles accounting for "a large share" of the discs. The records are, according to Friedman, from "the middle to late '60s up to '73."

"How many other places are there like this?" I asked.

"I don't think there's any like this in the world," he replied. "No business person in their right mind would have held on."

"So...you're not in your right mind...?"

Show me the records!

All talk and no records makes Mikey a dull boy, so I axed for the guided tour. What's there? Well, first, if you're a savvy record buyer who's thinking, "Ah, record-club records, they never sound as good as the commercial releases," you're right. But not to worry: While major-label record-club releases licensed from other companies were almost always mediocre remasterings from tape copies, done by faceless, uncaring technohacks and usually featuring nonauthentic paper stock and bad printing, not to mention ground-up BIC-pen pressings, all of the RCOAs are identical in every way to the actual label release except for a small disclaimer printed inconspicuously on the jacket. Why? Because all were pressed by the original label.

So the copies of The Allman Brothers Band I examined were identical to the Atco/Capricorn original (SD 33-308): same textured gatefold paper stock, same fine printing job, same thick, beautifully pressed pre-WEA vinyl (mastered, I believe, by the great George Piros), and unplayed! Untouched by a Sears-Roebuck pull-down changer, flip-out speaker, tote-to-a-party "stereo." Untouched by hemp-stained hands. Stone mint. Of course, in the nonaudiophile "collector's" marketplace, sometimes record-club issues are more valuable because they're rarer. Go figure.

Yes, the story was true: There were 650,000 unplayed records in this York warehouse, and there were multiple copies—dozens of copies—of records you might want. Lenny Bruce's Carnegie Hall Concert in the original full-color three-panel UA pressing? Two-and-a-half boxes of those. Bonzo Dog Band albums? Lots of 'em. The Stax original of Albert King's I'll Play the Blues for You, recently reissued by Analog Productions. Sure, you can find used copies of Stevie Wonder's Talking Book at a used-record store or garage sale, but where else are you going to find boxes of unplayed original pressings? Maybe you'd like a copy of the spectacular-sounding Them Featuring Van Morrison, a two-LP set on Parrot records. I counted more than 20 copies; there probably were more.

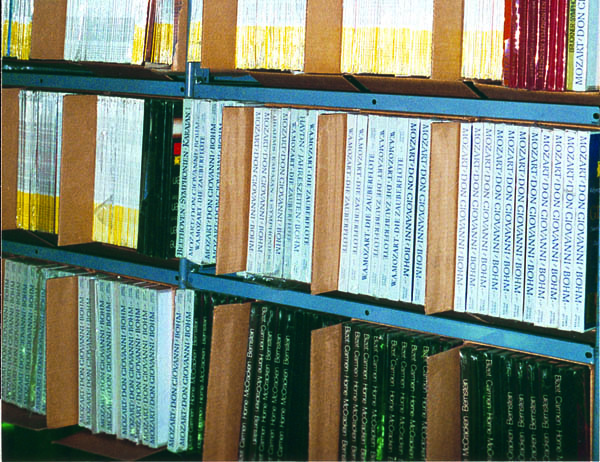

How about a wall—a whole wall—of Chess and Checker pre-digital unplayed LPs, Bo Diddley, Muddy Waters, and Chuck Berry among them? There's a Berlin Wall's worth of DGs too, including a few dozen copies of the much-sought Carmen with Bernstein conducting. Maybe your taste has finally matured to where you can hear the beauty in the avant-garde blues of Captain Beefheart's Trout Mask Replica. ("It's the blimp Frank!!!!! The mothership!!!'') Boxes of Beefheart originals on Straight Records. And multiple copies of The GTO's Permanent Damage. Where ya gonna find that, bunky?

I saw boxes of Roy Orbison albums I'd never heard of—like Milestones and Roy Orbison Sings. Sure, not peak Roy, but when you gotta fill out a collection, who you gonna call? Where else can you find multiples of unplayed second-pressing Mercurys, including Balalaika Favorites? Or half a wall of Verve jazz? Or a box of mint, unplayed copies of The Who Sell Out—with uncut corners? Now that's a sight worth driving all the way to York to see.

The thin end of the wedge

Of course, there's a downside to all this. For one thing, there's a lot of junk too. Want to buy a few hundred copies of Sonny and Cher Live? I didn't think so. Well, maybe to throw at Sonny. Need a Lawrence Welk fix? And about those Chess and Checkers—unfortunately, many are Dynaflex-thin and electronically reprocessed for stereo. Think about it: the late '60s to early '70s. That era was, for many labels, the nadir, the pits of record production. And then there's what's not there at all: no Columbias, no RCAs, few if any Blue Notes or Prestiges, not many Capitols, no Impulses—and, overall, not a great deal of truly collectible, much-sought-after vinyl...though there is some.

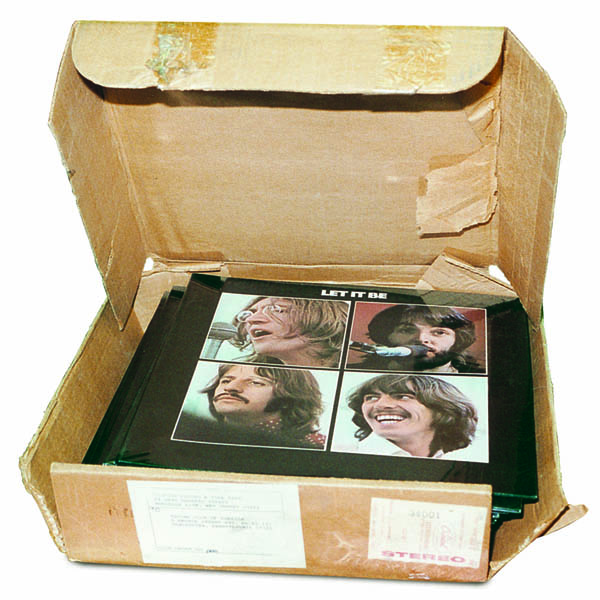

The collection took a year to catalog and assess. The valuables were removed to a smaller room, where they take up two long walls and a set of floor-to-ceiling stacks in between—probably about 25,000 in all, by my guesstimate. The really rare stuff fit easily on Friedman's desk: a mint, unpeeled Velvet Underground "banana" cover; a few copies of Introducing the Beatles on VeeJay—unplayed and not bootlegs. (I forget which song selection and back cover.) Where can you find that? But even of those culled from the collectibles, none were the big prizes—though a full box of sealed, original Let It Bes in the original Capitol pressing plant mailing carton will probably be a big auction item.

The Plan

Did I say "auction''? Don't worry, only a few hundred items are really auctionable, though Friedman told me that if he's got only two or three of an item—whatever it is—he's considering auctioning it. Most of the records will be sold in a set sale catalog being readied as I write this, and probably available as you read this. And don't let my negative assessment give you the wrong idea—that was just to keep your pants from catching fire. There are a lot of great records in this inventory, something for everyone—except digiheads, of course.

Friedman sees the market for his records consisting of audiophiles, the Goldmine crowd, and foreign music buyers interested in anything American made by American artists. Friedman plans to issue "certificates of authenticity" with the collectibles, though I'm not sure most buyers really need that kind of assurance: They'll know they've got the real thing by touching, smelling, and looking at it. How much will your average, run-of-the-mill record like Talking Book sell for? How much would you be willing to pay? I figure you can go to a used-record store and find a nice original copy for under five bucks. The CD buyer will pay about $12 for a poorly packaged, glassy-sounding replica, so would you spend $15 for an unplayed original? I would.

How many records did I go home with? None, of course. How many will I buy? I'll be checking the catalog along with you. Friedman's done direct-mail; he knows what to expect when the catalog hits the public. The plan is to advertise the collection in all of the usual suspects, and it's very possible consumers will be able to drive to York and buy "factory direct" for the same price less postage. But don't drive down yet—at press time that hadn't been decided.

Meanwhile, if you want a catalog you can order one from Quality Vinyl and CD Outlet, 25272 Ripleys Field Drive, South Riding, VA 20152-4441; or call (703) 327-4809; or e-mail qvinylaol.com . Tell 'em Mikey sent you.

Online vinyl

Lurking on the Internet is not my idea of a good time, so I can't say I've spent many hours looking for vinyl buying sites. But a few have popped up that are worth a look. One, run by Timewarp Records, gives each record its own page. The records are carefully graded, cleaned on a VPI cleaning machine, and come with a money-back guaranty. Owner Howard Rogers told me he's about to acquire a huge jazz collection from a radio personality; if you're into jazz, you ought to stay on top of this site.

Another site I've tried is run by Vinyl Tap Records in Leeds, UK. It's a well-organized site, and, whaddaya know, most of the records are "imports." As a birthday present to myself I ordered an original Parlophone yellow-and-black–label mono pressing of Sergeant Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, listed as absolutely mint. By the time I was finished with shipping, it set me back about $100. But hey, you don't turn 50 every day.

When the record arrived, it was anything but mint. It had been cleaned, but, held up to the light, I could see it had been around the platter many times. With mono records you can usually get away with more plays—there's no vertical modulation—but a quick spin revealed lots of audible wear. I e-mailed Vinyl Tap, got an apology, and after they'd received the record back I also got a full refund, plus another e-mail acknowledging their mistake. To err is human. I will definitely try Vinyl Tap again.

And there's a great piece on the vinyl resurgence, by Jody Rosen on the MSNBC Web site. I don't know how long they'll keep it posted, but check out msnbc.com/news/73112.asp (link no longer valid -ED)—you'll like it!

Finally, yesterday's New York Times carried Joel Brinkley's front-page story about the new proposed DVD audio format. It began, "Now that most Americans have stashed their turntables in the attic...'' You'd think a guy who writes for Stereophile Guide to Home Theater would know better, but noooooooooo. I fired off a letter to The Times citing statistics that prove otherwise. We'll see if they publish it.