Bonnie "Prince" Billy Grants a Rare Interview--Pt. 1

With a new album "The Letting Go" just out (Drag City DC420 LP/CD) and a co-starring role in "Old Joy," a film Entertainment Weekly's Lisa Schwartzbaum (happens to be a second cousin of mine!) called "The Best of The (Sundance) Festival," and The New York Times's Manohla Dargis wrote was "A Must See..." and "One of the most persuasive portraits of generational malaise-a tentative hope-to come from an American director (Richard Reichardt)in recent memory," Will Oldham (a/k/a Bonnie "Prince" Billy") is on an impressive roll.

In February of 2003 I was given the rare opportunity to interview Mr. Oldham in a small lower East Side hotel where he was holed up for a day meeting with a a carefully selected group of journalists. Mr. Oldham was then publicizing his newly released album "Bonnie 'Prince' Billy Sings Greatest Palace Music" a collection of his favorite tunes re-recorded in Nashville with a group of well-known studio cats. For Mr. Oldham, who usually prefers more intimate, less commercial settings, the recording was as unusual as his consent to give journalists face time.

Described as "reclusive," "enigmatic," and even "mysterious," Mr. Oldham proved to be open, charming and forthright.

Though the interview sat in the can for a few years, given Mr. Oldham's current activities, it seemed like a good time to publish it. Elsewhere you will find a discography and a series of mini-reviews covering many of the prolific artist's releases.--MF

Michael Fremer: Your voice sounds very rural, very isolated, and yet I know that that’s obviously not how you grew up, that’s what you absorbed.

Will Oldham: Well, I don’t know actually. I think that the records sound like that has everything to do with economy, across the board economy like, making records and not having money to make records so not wanting to deal with more elements than you could deal with to get a record done and to convey a song.

MF: That’s on a technical level though.

WO : Yes, but on a technical and also beyond certain musical abilities. But so I think if you play or if I played, if you picked any song that had a beginning, middle and an end, a chord structure and lyrics, and I played it right now into this tape recorder, no matter where the song came from if it was a song from modern day, you know, Mississippi hip-hop and if the lyrics could be sung and not rapped, people would say, oh, that sounds country, you know, and it’s just because I come from Kentucky and I’m playing on a six-stringed acoustic instrument. People say oh, that sounds folk and country. It’s just like, oh, well, you know what, it’s just me playing a song that I just heard off the radio. It’s not a stylistic choice; it’s just me playing a song, and you’re imposing a style, you’re saying it sounds like this, you’re saying that I’m influenced by this, but really I have this voice and these two hands and I’m playing this instrument and I’m not a music geek who can play anything. I can’t play anything. I can just go ging-ging-ging-ging – you know, I can’t go bludleeedleedledeedle or joomjoomjoom kachucka bowbow, you know, I just can’t do it because I don’t know how to do it.

MF: You’re not a funk master.

WO: No. I mean I’m not Prince where I can play every instrument, do it, make them say anything that I want them to say, the instruments, because I don’t spend my time doing that. I spend my time more thinking about how a song works in general rather than how it works in the specific, just because I don’t have that kind of math genius brain.

MF: I’m not even talking about what arrangements are in the music or what rhythmic thrust you might use. I just mean as far as what you evoked on those albums…

WO: To you? From Boston?

MF: From “New Yawk.” Yes. I mean truthfully writing about music is one of the most distasteful things that you can do.

WO: Right, I imagine.

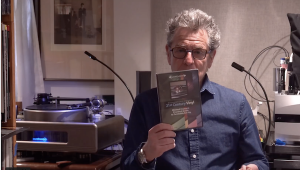

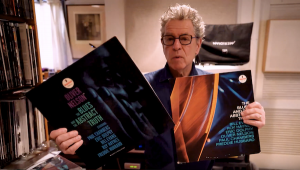

MF: It really is. It’s because it’s -- well, that’s my problem though. But what I mean is listening to your voice and if I didn’t see you, if I’d never seen you, and, in fact, when that record, which was the first record I ever heard, this one (Viva Last Blues Drag City 65 LP from 1995) -- I didn’t see you. I didn’t know what you looked like, how old you were, who you were, where you were from, and it just evoked a very old soul. But the new one (Bonnie “Prince” Billy Sings Greatest Palace Music) sounds to me – it’s a greatest hits compilation on a certain level but beside that it just sounds much younger. Is that conscious or is it just something – who you are at this point in time?

WO: I don’t know. It’s hard to address it sounding older or younger. At that point (1995) things were more of a struggle, it was more of a struggle – just being in the recording studio was more of a struggle, and making songs and living on a day-to-day basis was more of a struggle.

MF: You sound very liberated on this record. It’s just optimistic.

WO: Yes, well, there’s a liberation that comes with working with these – all or maybe three of the vocals were done live with the Nashville band, and when you’re working in independent music and working with all different kinds of – you know, most of the musicians I work with have other jobs, day job, etc., so there’s other things filling their brains besides music, and all of a sudden here I’m sitting in a room with men who have been working in music for decades and all that fills their brain is music. In order to survive, they have to think about music all the time on an emotional level, on a technical level, and specifically about recorded music because these are session guys and that’s their bread and butter is how it works in the studio and it has to work if they’re going to get another job. And they’ve got enough jobs at this point that they’ve done it right. So, it’s completely, completely liberating to just be like, you know, rather than always having to hold back and think like how am I going to express this, how am I going to phrase this to this musician and get them to play it this way. And then I don’t have to because they recognize – they know why this chord goes into this chord and why there’s no bridge in this song at all. To them, they hear it once and they say, oh, I know how to get this song dramatically from the beginning to the end of the song. And then, I’m just like you mean all I have to do is sing?

MF: And it buoyed you up?

WO: Totally. Totally. Yes. I mean I felt like I could – in some ways I have a fairly limited voice but I felt like I could do more with my voice in that recording session than I’m usually able to do just because I’m usually hearing everything and thinking like how is this going to work, how are we going to mix this, how are we going to do this thing. And this time I was just like, oh, all I have to do is sing.

MF: Yeah. And yet you must have gone into it with a certain amount of wonder about how – you’re with these guys, they’re there every day, they’re these hardened pros, how are they going to relate to you, how are you going to…what was that like?

WO: Yeah, well, I figured – like I brought – like I made demos of 21 songs figuring that we’d get at least 12, which was my goal. I was thinking this is going to be a weird experience, I can’t count on the fact that it’s all going to be productive, but I figured with these sessions with these guys and then if we wanted to do the overdubs with other musicians that I work with a lot --

MF: -- in different places.

WO: -- in different places, that we could come up with 12 songs, so it was knowing that it was going to – not knowing – knowing that it was going to be a different experience and not knowing how successful or how satisfying or whatever.

MF: Well it turned out great. It’s wonderful.

WO: Yes, it turned out…

MF: And how did you interact with them in terms of – you decided on the guys you wanted to hire?

WO: Mark Nevers who recorded this record and recorded the last record we did had come up in his career in national sessions in the ‘80s and ‘90s on lots of hit records.

MF: Pop?

WO: Pop, yes, Alan Jackson and [OVERLAPPING VOICES].

MF: Yeah, and what is that, that’s pop?

WO: It’s just modern country, it’s just like --

MF: Eagles.

WO: Yeah, it’s post-Eagles, post-Eagles Nashville. And then he got disgusted finally with it and left and started his own studio and started working with independent musicians. But he still had connections and so he was like well, I know – I think I can get --

MF: And you went to him. You decided he was the guy you wanted to go with?

WO: Well we did a record together (Master And Everyone Drag City 233 LP) because he’d done a record with my friend, David Berman and the Silver Jews that I liked a lot, and so I went to him, we made a record, and just for a couple of overdubs, we were in Nashville, a couple of overdubs, a woman singing and a cello player, we called in some pros. You know, the cello player we got from the Yellow Pages in Nashville and the woman, we called the singers union. And both of those, it was just like – that was like so easy to get done what I wanted to get done on some levels.

MF: The resources are there.

WO: The resource is there, I was like wouldn’t it – it’s like wouldn’t it be cool to make a whole record like that?

MF: Was that like an epiphany?

WO: There’s been different times when I – I am very influenced by the people that I work with, very influenced by the people that I work with. So I am aware, you know, if I work with – I made a recording of a song years ago with a group that my younger brother was in called the Pale Horse Riders out of Louisville, and they were super – it was crazy… insane. The one guy in it who plays whatever, sometimes he plays flute or other things and when we started this session we recorded in an abandoned hotel in downtown Louisville and he had to do like an Indian blessing of the room first and that affected everything, that affected the way I sang. So in some ways it’s a revelation but in some ways it’s really exciting to know from listening to all different kinds of music, knowing that it has an influence and then being able to see the influence by putting myself in different situations, to go work with these people and know that there’s something in me that I was nurturing that was prepared to be in this situation, that it wasn’t just like once we got in the room with these guys it was a tidal wave and I was in over my head and I just couldn’t keep up. It was more like “this is great.”

MF: You were in the right place at the right time and everything – you know, but you wouldn’t know that going in. You’d hope.

WO: You’d hope, yeah, and not know if it was going to sound like I was a fish out of water or if I could get into where they were coming from or where they took the song. So Mark hooked up with – Mark knew specifically the acoustic guitar player, Bruce Watkins, and Bruce assembled this team of the A-list session guys.

MF: Did they have fun working with you?

WO: Yeah. I think they had fun working with me. I can at least say objectively I think that they did because they don’t get the chance to work with each other as much without having – and they don’t get a chance to work on stuff that isn’t the modern country stuff which I think they have mixed feelings about. It puts food on their table but it’s not the music that they love, and this music was closer to music that they like playing and there were certain songs that afterwards they were all just in super high spirits laughing, just like “that was fun” and getting to play off each other.

MF: And did they know who you were going in?

WO: No, they had no idea. I don’t even think going out that they had any idea. [LAUGHTER]

MF: And when they were finished do you think they would be curious to look at the rest of your work?

WO: I didn’t know and I didn’t want to worry about it because there was enough to worry about. But just a few weeks ago or maybe like a month ago Mark wrote me and he said, he’s like “the guys are asking, they want to hear the recording. Is it okay if I play it for them?” And that was just like – you know, I just figured they would have forgotten about it so I thought that’s nice.

MF: And I’m sure they were happy with what they heard. I imagine they would be because I was totally taken by surprise because it’s so different.

WO: Yeah. I mean I know – there’s a couple of those players that I knew specifically, not going in but as the session evolved, I was like wait a second, did you maybe play on – you know, and then realizing where I’d heard the things before, and knowing that it was things that had jumped out at me before, on recordings that might otherwise have been not as interesting or not as exciting, but knowing how this person had contributed to make that a valuable recording. I’m a big fan of Patty Loveless’s records, almost all of her records except for two records ago she made a post-“Oh Brother, Where Art Thou?” roots -- return to roots record which I thought was a waste of time because her records were already cool enough because it was obvious she was bringing that to a slick country sound.

MF: Isn’t it ironic that she would go back to make a record that would be a commercial twist that would be a roots – I mean it’s totally backwards and that’s probably why it didn’t work, at least for you.

WO: Yeah. It didn’t work for me. I think that she got – maybe turned on new kinds of fans and got to do like those “Oh, Brother, Where Art Thou?” tours, which I bet in the same way were fun because of all the different bands that were playing together and got to do shit together that they wouldn’t have gotten to do if that movie hadn’t been made, you know? It’s just like activate – open lines of communication and things like that.

MF: With fans, too, which is great. It was terrific for that.

WO: But yeah, as a record it doesn’t work.

MF: So in making this record you sang live?

WO: Yes.

MF: So all those are live tracks.

WO: Yeah.

MF: Did you punch anything in or is it…

WO: There’s three songs where I redid the voice, either because – I think one case was because we turned it into a duet; one case was I just – there were mistakes, live mistakes, and then one case I just didn’t like the whole vocal presentation.

MF: But for the most part they’re full live takes?

WO: Full live takes.

MF: And with the core musicians.

WO: Uh-huh.

MF: And then you just over-dubbed, you went home to different home studios or different smaller studios?

WO: Yes. We did all different things. We did some things in Nashville, sent the tapes to a couple people who were too far away and then traveled with the tapes like to Milwaukee to a studio there, to South Carolina, back up to Kentucky where I live.

MF: Was this all done digitally?

WO: The original tracking was done to 16 track two-inch tape, analog, with a Pro-Tool safety going on the whole time, and then all the overdubs that we did in Nashville would go to analog and then we would take those tapes over to the studio where we were mixing and he would then transfer everything to Pro Tools from the analog because we had so many tracks going on.

MF: As far as I’m concerned it’s amazing you did that much analog and it’s good that you did that much analog.

WO: Yes, Mark is a big proponent of analog. He loves his two-inch 16.

MF: It’s so much better it’s ridiculous, and it comes through, although the mix – now, were you involved in the mix?

WO: Yes.

MF: There’s an amount of compression in there that gives it that that punch.

WO: Yes, and that’s because that’s what Mark’s come up to, that’s how he learned recording, lots of that compression.

MF: It’s commercial sounding but it’s not like dead. A lot of people who go in to record now, ‘I want it louder than the last guy,’ and then there’s no dynamics, it’s flat. This isn’t flat, this is this kind of – and it goes with the music.

WO: Yeah. I think the original sequence that I came up with 16 songs, listening to it I was a little frustrated because there was a little bit of flatness because Mark had souped everything up so much. So then there are maybe five songs that my younger brother and I remixed at his studio which is in Kentucky to bring some of the dynamic that I remembered from hearing it right after we did the original takes. You know, a thing like I loved that, that take was perfect, and then I was like, well, now, whatever, the drama is gone or the closeness is gone or something and it’s because everything was made really loud, really in your face, and it was just like it wasn’t necessary for every song. So we did that and then I think it fits in seamlessly with the others and it gives the record a little more dynamic.

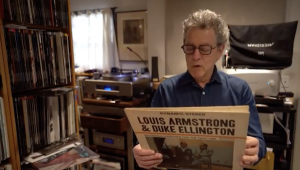

MF: This record I recommend to a lot of people and some people have trouble with it, but Viva Last Blues (Palace Records/Drag City PR4/DC65) which is the first thing I ever heard that you did, I went how come I never heard this before. And I know also Steve Albini I happen to know is a fantastic engineer. What was it like working with him when you did that?

WO: It was great. I’ve known Steve for a long time because I was a fan of Big Black when they were around and he handled orders for t-shirts and things like that, so I remember sending him money for a t-shirt and then going to see him play in Newport, Kentucky in ’85. “Steve, this is Will Oldham. This is Steve Albini.” He’s like, “Will Oldham from Louisville, Kentucky? I owe you a t-shirt. Hold on just a second,” you know, and getting me a t-shirt.

MF: He’s such a good guy.

WO: Yes, and then, you know, we all stayed at the same apartment that night, and then I knew him increasingly over the years, and I wanted to work with him but honestly couldn’t afford it for the first two records. So this record (Viva Last Blues), I made him come to – because he’s great, you know, but I made him come to Alabama where I was living because I didn’t want him to be able to get any phone calls or anything like that for a while.

MF: Yes, I’m sure he’s a magnet, lightning rod for stuff.

WO: Yes. And he has a full life and so to sort of isolate. I like everybody to be isolated when making a record so that that’s all you think about, and at that time we would make records in a week, and that’s not too much to ask of everybody.

MF: Where in Alabama?

WO: It was in Hueytown, Alabama and the studio was called Bates Brothers Recording. It was about 25 minutes outside of Birmingham where I was living, an industrial area, a little industrial – like a strip mall but not commercial – it’s all offices. And they just had their studio in there and they record mostly gospel.

MF: These are all disappearing, aren’t they? All these things are going away.

End of Part I.......