The "Dean" of Alternative Rock Engineers Steve Albini

MF: Do you have studio that you work out of now?

SA: I have a 24 track studio in my house-all top of the line equipment-but more importantly than the studio, I have a large collection of very high quality microphones that I tote with me whenever I go anyplace else to make a record.

MF: How did you accumulate them and what are some of them?

SA: Well I got them by buying them......There's the Calrec Soundfield- an amazing microphone that sounds really good.

MF: That's the Ambisonic microphone.

SA: They make a version of it that's a simpler version that they call the Ambisonic stereo microphone. The idea is a really good one. Are you familiar with the M-S stereo microphone?

MF: Sure. Most of our readers understand that.

SA: If you imagine the mid-side principle where you take two microphone capsules and electronically add and subtract their components if you expand that into a tetrahedral array you can create virtual microphones of virtually any polar pattern, and virtually any stereo spread and virtually any front to back dominance by using these different capsules inside the microphone head itself. You can use those as components from which you synthesize a stereo image and that is the main feature of the microphone- that it was developed as a very versatile stereo microphone that would allow you to do an awful lot with the stereo image. What a lot of people don't recognize is how nice this microphone sounds. It's a very crisp, very dry, natural sounding microphone. It doesn't have any of the currently quite trendy mid-range-y quality that a lot of vacuum tube microphones have, and it doesn't have any of the sort of forgiving tonal irregularities that a lot of other microphones have. It doesn't have big peaks and bumps in its frequency spectrum that are flattering to certain things and not flattering to others. It's relatively flat, and considering how complicated an array it is, I'm amazed it's as flat as it is.

MF: When you mike a band- lets take the P.J. Harvey album which sounds like its recorded live in the studio…

SA: Its essentially live. There are always moments of uncertainty where somebody does something he wants to fix later...

MF: You can hear mistakes in there that were left in, which I think is great. So how was that miked?

SA: On a drum kit I will generally have more microphones than on anything else. A drum kit is a pretty complex instrument, so there'll be on each tom a top mike for the attack of the stick hitting the skin and then a mike on the resonant head to pick up the resonant tone of the drum, and then those have to be balanced electronically to simulate what your ear hears as a natural summing effect of the room.

MF: So in other words, what you are trying to do is- in the audiophile community there is this idiotic kind of ideology- you've got to use a single point stereo microphone to record the whole event and most if sounds like shit. And the point is, what you are trying to do is use the technology to create the reality.

SA: To interfere as little as possible- that's my goal. To make a recording the represents as accurately as possible what the band is doing and as a technician, as a producer, whatever, to not interfere with the stuff that goes on inside the band- all of their decisions about what kind of songs to play how they should play, the kind of instruments they should use-I consider that almost sacrosanct-that's their game.

MF: So you are a producer and an engineer?

SA: I don't like the term producer although generally speaking when a big record company hires me, it's as a producer. I don't like the term producer because to me it implies a way of doing things I want no part of-the sort of pushy bastard that organizes things and tells the band what to do.

MF: But does the band rely on you for feedback? How does this sound? How was that performance? What's the feel of that?

SA: In the sphere of musicians I deal with, that's a normal part of interaction with anybody. They would expect that from the guy that drives them from the airport. It's definitely not the star strata of artists. It's not people that expect to have “yes men” around them-with very rare exceptions. There's always an amount of hemming and hawing about what should be done and what sounds good and what sounds like shit. It's not the case that I'm hired because I bring an esthetic that I can impose on them. And that's the case with most other producers.

MF: Well, of course that begs a certain question. There is an esthetic. It's a natural esthetic. Its allowing the band to come through. Which I think is positive. It's neutral in the sense that it's what the band is that you are trying to bring forth.

SA: Occasionally bands that have had other studio experiences expect when they go in to the studio to be messed with more. They expect to have a metronome set up for them. They expect to have guitar overdubs, for example.

MF: When they go in with you, do they sometimes feel naked and inadequate for a while until they get used to your style of recording?

SA: Occasionally people feel like I'm just trying to make life easy for myself. Like, "what do you mean you don't want to fix that?" Because I like the way it sounds, and because fixing it would make it sound worse. " Oh it will be simple for me to fix it. Just let me go down and fix it". Fixing it is not necessarily a good idea.

MF: What happens in a situation like that? Who wins out?

SA: The bottom line is, I work for the band. If they tell me in a clear voice that we want to do something one way, and even if that goes against every element of my own personal psyche, that's ultimately-they're the boss. If someone wants me to, I'll replace a snare drum with a sampled champagne bottle. I always make it clear what is a good or bad idea.

MF: But you try to mike everything in stereo, so there's not a lot of pan potting.

SA: I use stereo an awful lot more than most recording engineers.

MF: Absolutely! You can hear that in a minute. And do you have a room pair or ambient mikes?

SA: I generally have several pairs because when you're doing a set up for a recording if it's a classical piece, you are recording something that has a very predictable dynamic and something that you may well be very familiar with. I record a couple of hundred records a year and in each of those records there are from three to eighteen songs being recorded, each one of which will have a peculiar specific personality so I try to set up things that allow me the flexibility of having already set up the perfect ambient mike pair. Generally speaking I'll have either the Soundfield mike or an M-S stereo micrphone set up as a stereo pair in front of the drum kit. I'll have another stereo pair of ambient mikes very distant from the drum kit, and then I'll have spot mikes on the drums and a stereo pair of overhead microphones so that the entire range of sound from very close to very ambient is available on tape without having to do anything electronic and without having to spend tedious hours fiddling around with one pair of microphones to get them in the right place.

MF: How long generally does it take to do a whole record with you engineering it?

SA: It takes a lot less time with me than with big shots. I just made an album with a band in a weekend- two days. The longest time that I've ever spent working on one album is a little under three weeks.

MF: Lets just quickly deal with the analog/ digital debate. What do you think?

SA: The consumer formats for digital today are horrible. Everything on the professional level has been designed to meet but not exceed the standards of the consumer format. The CD is a very crude digital storage medium, its not permanent, it has a lot of error, the sound quality I don't think, is close to a good analogue system. Everything from microphones, through converters and digital processing devices, equalizers, transfer consoles, mastering desks- everything has been designed to meet, but not exceed the standard of the CD which is a 16 bit word, a 44.1KHz sampling rate with a minimum of oversampling and fairly healthy error correction. There is serious error correction going on at all stages of the digital recording process.

MF: Now when you heard the P.J. Harvey album on that system (Apogee's

newest hybrid speaker with Krell electronics and digital front end) that was an analog recording I assume...

SA: That was an analog recording and the vinyl copy is an all analog mastering as well, which is very rare today. The guy that mastered it is a fellow named John Loder. He's a very wise engineer. He runs a studio, a record label and a distribution company in England called Southern Studios. He was involved in one of the very first experiments with digitized audio. He's older than me- about forty seven or so...

MF: An old guy like me.

SA: And when he was in college as part of his post-graduate work he was involved in digital encoding of audio for the purpose of encryption for military secrecy basically. And the telephone company basically was responsible for all of that stuff. And he understands digital audio better than just about anybody. And as a result his studio is and has remained staunchly analog. High quality analog recording sounds better, is easier to work with...

MF: You are the first person to tell me that! Most people say well digital sounds lousy but the convenience factor, the editing...

SA: Once you get to the stage where the music has been digitized and stored as files on a computer and you are sitting at the computer, yes, it's very easy to shuffle things around, but for example if you're transferring an hour and a half of music and you get to one point on the tape where there's a program peak that peaks out the digital meter you've ruined the recording, you have to start over, you have to lower the signal level of the entire program to acommodate that one peak and there's very serious degradation in the sound quality of music that's recorded at anything less than the absolute peak level on digital media. And that's why classical music enthusiasts, people who listen to music with a real wide dynamic range where a large portion of the program material is at a low volume level, those people were some of the first to recognize that hey, CD sounds like shit. And that's because if you're listening to something that's at minus 20 from a 0 dB reference on a CD, the actual resolution of the word at that level is something like 12 bits, 10 bits, something like that. At 10 or twelve bit encoding, if you listened to that next to the source itself, there's no way you would accept it. Everyone talks about how CD is a 16 bit system. Its 16 bits when you're pinning the meters. When you're not, its not 16 bit. Regardless, virtually all of the digital recording that are being done these days- the stereo masters- are being done on DAT because its convenient- its a nice size. Its a terrible format! It was invented as a replacement for the home hi-fi cassette. In that capacity it would be fine. For temporary recordings of music that exist in an archival form where you just want to listen to it on a convenient size, DAT would be a perfect choice but the American major label industry blocked DAT- which to me seems like such a psychotic move.

MF: And now look at what we have! Minidisc and DCC.

SA: Neither one of which is going to survive. Even people who own CD players will recognize that these things are marginally more convenient than CDs because you can record on them, but they sound like shit. That DAT has usurped the stereo analog recorder in the studio is really criminal. One good thing though, is that it allows people like me to buy really high quality stereo analog recorders at really low prices. (Everyone laughs).

MF: What about recording consoles?

SA: It amazes me when I see displays like this of high end audio gear, people spending five, seven, eight hundred dollars on speaker cables...

MF: Eight hundred? How about fifteen thousand! (the Kimber 88).

SA: For fifteen thousand dollars I'll record and mix five or six record albums for you how's that? Anyway, I've been to the finest recording studios in the world. I've seen how these things are put together. I've looked inside the guts of the finest recording consoles in the world and there are signal paths in every piece of home audio you listen to at home, if they were like these, you'd pull your hair out looking at this.

MF: That's why many high-end engineers try to bypass the console altogether.

SA: Recording studios are put together with some regard for audio quality, but the principle guiding factor is A: what do the clients expect to see? In other words what have they seen at other studios. B: Features clients have come to appreciate, and C: cost. If things are too expensive and too cumbersome and too weird no matter how good they may be, they will never gain wide acceptance in the studios.

MF: So if you go to a recording venue that has a lousy board, what do you do?

SA: I deal with it. I'm not such a prima-donna and my clients are not so rich that I can afford to make decisions like "oh, this console in inadequate we have to go somewhere else". I can't do that.

MF: What kind of tape do you like to use?

SA: I use Ampex 499 for the mulititrack recordings. There are physical problems with the tape that competes with it, Scotch 996, that I think bodes very poorly for those master tapes in the long run. Last year I had to do re-masterings of records that were made over the last ten years and the analog tapes, generally speaking, were in very, very good condition with a few exceptions. And those had a sticky binder leaching and I had to meticulously clean every inch of a master tape and it was real pain in the ass. But, when it was done there were pits in the tape, there were places you could see daylight. But you could play it and it sounded fine. If that had been a digital tape that had deteriorated even one percent of that amount, not only would you not be able to play it and get anything like music out of it, there would have been no way to retrieve the information off of it. It would have been lost. But anyway, the thing that bothers me about recording studios in general, is that the people that run them have the attitude that well, "if it sounds okay to me and if it works for my normal day to day usage, there's no reason to improve it, no reason to make it easier on you, Steve Albini, when you get here," and so when I get to a studio and find problems I make a log of them and try to get them fixed. And that's why I brought Bob (Weston) with me in February when I was making the P.J. Harvey album to a studio that was acoustically outstanding-a place called Pachyderm in Minnesota-but there hasn't been appropriate maintenance done on it. And the console, an old Neve console that sounds pretty good, and I know there would be problems. And I brought Bob along when I was doing the Nirvana album (also at Pachyderm) because I knew there would be problems. I wanted to be able to find something, pull it out, throw it to him and say, "Fix this". And that was a real luxury. That was the first time there was enough money to bring someone like Bob along.

MF: I would hope so!

SA: Most people that do what I do are in it for themselves. They want to make a lot of money. They want to be popular and famous and have a lot of influence in the industry. I really don't give a shit about that kind of stuff. I get paid far, far less than anybody else that does what I do.

MF: I can relate.

SA: I make records for free.

MF: You mean you don't aspire to be Chris Lord-Alge?

SA: Who?

MF: When you recorded the new Nirvana album (In Utero) did anyone in the band say anything about vinyl versus CD?

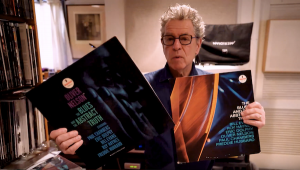

SA: Sonically I don't think it's an issue with them. Esthetically they prefer vinyl- they grew up with records and everyone has a romantic attachment to it.

MF: Will the new one come out on vinyl?

SA: I don't know. I'm not involved in that. I dislike the record company world so much, I dislike the professional music industry so much that I didn't want to deal with it even in the least bit. My agreement with the band was, I will deal directly with you, you will have to put up with the record company. And to this day I haven't said a word to the record company.

MF: Did Nirvana approach you about recording In Utero?

SA: Yes. I don't approach bands unless it's a very small scale band that might be intimidated coming to me, otherwise if I take a real shine to them I'll approach them. Generally speaking bands look me up.

MF: Did they come into the studio ready to go, well rehearsed?

SA: Yep. They were as prepared and as together as any band I've worked with. I have no reservations about how they handled themselves in the studio. They were very professional and very efficient. Speaking of the Nirvana Nevermind LP, I'd be very surprised if it was mastered from an analog tape.

MF: It was. Howie Weinberg did it.

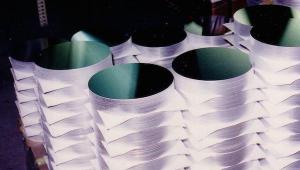

SA: The vast majority of mastering houses are using digital workstations instead of analog mastering consoles. And even those that are using analog consoles- when a record is cut you have to have the cutting lathe informed about changes to the audio program...

MF: The preview head.

SA: Right. The standard method is to run the audio across a preview head and a parallel set of equalizers or level controls or whatever, duplicate what you've done to the program channel and that preview head tells the lathe how it should behave. “This is a big bass break, we're going to need a big wide groove here, so make space.” Almost without exception mastering labs since the mid-eighties have gone to using a digital delay line instead of a preview head. The PJ Harvey album is one of the few records I know of where I insisted that they use the analog preview head instead of the digital delay line- and it was done at Abbey Road studios which is a very fine facility and even there he had to hard wire in the preview head so the cut could be done in the analog domain.

MF: Did you exercise that kind of control on the new Nirvana album?

SA: No. I can seldom exercise that kind of control once the tape leaves the studio.

MF: How did the CD of the PJ Harvey album sound on the Apogees? Brighter than how you mixed it?

SA: Yea, those were very revealing speakers, tonally the speakers were quite flat. I tend to listen to speakers that are thuddingly bass heavy.

MF: What do you monitor on?

SA: Near field monitors.

MF: Like?

SA: Yamaha NS-10Ms

MF: Why? Why? Why?

SA: Because they sound like shit! And if you can make a record that sounds convincing on Yamaha NS-10Ms, then you have achieved something. When you get to a system that is flatter and has more detail, you will not be losing anything. For a more accurate monitor I like the Westlake BBSM 4s. A dual cone nearfield monitor with I think a one inch high-frequency driver. They sound great, good imaging, and detail and all that crap.