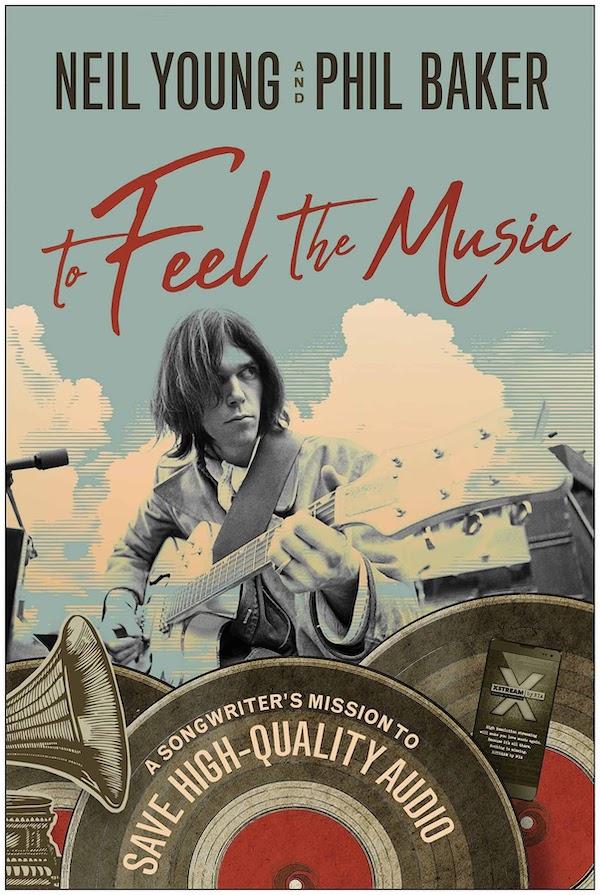

Neil Young and Phil Baker's Book "To Feel the Music"

From the (apparently difficult) development of his hi-res digital PonoPlayer to the adaptive resolution (192/24 on a good network) streaming of his online archives, Neil Young is by far the biggest name to advocate for improved sound quality. Having witnessed the degradation himself, over the last decade he’s tirelessly worked to bring high fidelity audio back to the masses in order to restore the indescribable “feeling” within music. Young, with Pono Music hardware developer Phil Baker, in September published the 250-page book “To Feel The Music: A Songwriter’s Mission to Save High-Quality Audio” (Benbella Books) about exactly that. The musician and developer contribute their own chapters, with Baker writing about two-thirds of the book. With insights into Pono’s development, reception, and collapse, To Feel The Music is bound to be somewhat interesting, right?

While Baker’s dive into Pono’s developmental challenges provides a compelling enough one-time read, Young’s chapters often show that, despite his devotion to the subject, he’s somewhat out of touch with the general public’s “accepted” listening methods. The PonoPlayer, a $399 expertly crafted digital music player, is a relatively bulky triangular prism that, as great as it may be (I haven’t heard it, but it was Stereophile’s digital product of 2015), still only plays music. Unfortunately, “normal” consumers who listen on the go aren’t going to carry an additional music-only device, much less buy it for $399. Still, Young isn’t to exactly blame for Pono’s failure: upon the device’s release, a spiteful consumer electronics writer published a negative review based on a quickly debunked “study;” and record labels jacked up the hi-res files’ price, making high-quality sound an elite luxury.

Further, Neil Young’s name is no longer significant enough to force a product into the mainstream. His middle-aged and boomer fans (many of whom are also audiophiles) might check out a Young-endorsed/headed product, but he can no longer reach most younger people. Younger consumers are, with few exceptions, immersed in the world of big tech’s lossy files, wireless earbuds, and strong marketing of such. Musician advocacy is always a step in the right direction, although most people aren’t going to buy products because of a classic rock artist’s name. The same applies to this book; its existence raises awareness, but how many audiophiles, much less non-audiophiles, will read it? I doubt very many. The volume provides a good sound quality technicalities primer for the uninitiated; for its niche appeal, is it imperative? Even as an audiophile, I found this book’s subject to be rather mundane, with no reread value. It’s hard to imagine even a retired diehard Neil Young fan who’s not an audiophile reading this book; that is, its audience is quite limited. Here, he essentially preaches to the choir. Beyond some announcement headlines and mediocre reviews, it didn’t make a splash.

The writing quality itself is lazily thrown-together; it often appears as if nobody bothered to edit. Baker at one point uses the improper plural “vinyls,” and many of Young’s chapters redundantly meander. Parts of it read like a Pono promotional essay, even though the brand died two years ago. “To Feel The Music…” is about 250 pages in approximately size 12 font, but could easily be edited to 180 pages. In three nights I breezed through its entirety, totaling 5-6 hours. Here are the mere five parts that make this book worthy, summarized:

1) Pono cost a lot of money. Suppress your hardware development dreams until you have millions of dollars ready.

2) Young writes, “I think if the highest-quality music audio were available at a reasonable price, the streaming companies would stream it, everybody would hear and feel better music, and the world would be a much happier, better place.” Similar to how Jeff Bezos has the ability to end world hunger if he so wanted to, streaming services could near us to world peace with a few minor changes. Seriously: if the increased availability of hi-res music can bring us even the smallest step closer to world peace, why haven’t we done it?

3) Steve Jobs cared about his listening experience, but not his consumers’. Young: “I had met with Steve Jobs in the past, and I knew how Apple would feel [about a directly outboard iPhone DAC - Pono’s first idea]. While he appreciated high-res music and listened to vinyl himself, he had no interest in high res for his products […]. When we spoke together, he told me his customers were perfectly satisfied with MP3 quality. He had one standard for himself and another for his customers. As he said, ‘We are a consumer company.’”

4) Neil Young met with both Lincoln and Tesla about installing Pono in cars. Car audio nowadays is all-digital, mostly with cheap parts and unnecessary “extras;” it’s all features, little quality. With the PonoPlayer’s output through an analog amp, the Lincoln engineers were impressed, but Young gave up after noticing their eight-cylinder engine-replicating background sound. Elon Musk and his Tesla engineers were highly skeptical of the Pono’s quality versus their built-in system and turned down a demonstration upon learning the necessity of a connection wire. Guess we’re not getting lossless versions of Elon’s SoundCloud tracks anytime soon. “A lot of people [don’t get it],” Young writes. “They can be brilliant in electronics, brilliant in software, and just very brilliant people. [Elon] is. But they sometimes don’t get [good sound].”

5) Apple purchased the Pono download store’s provider, Omnifone, in 2016, with the requirement for Omnifone to cease all operations. Pono got four days’ notice. Speculation swirls that Apple intentionally bought Omnifone to kill Pono, but the motive can’t be verified. After 7digital’s backend services proved too expensive, Young’s company admitted defeat.

I greatly appreciate Neil Young’s efforts; after all, everyone should have easy access to heightened music appreciation. Lossless streaming should be cheaper (Amazon’s $15/month Music HD service hopefully being a wake up call to others), portable devices’ audio processing should be carefully engineered, and the rising stigma against wired headphones and earbuds should reverse course (wireless can be nice for portable purposes, but not for real listening). Despite its appealing message, his and Phil Baker’s book is a sloppy, disjointed mess that isn’t as good and won’t be as big a seller as it should be.

(Malachi Lui is an AnalogPlanet contributing editor, music lover, record collector, and highly opinionated sneaker enthusiast. He’s soon anticipating a case of Light Wallet Syndrome, induced by an assault of Iggy Pop super deluxe box sets. Follow Malachi on Twitter: @MalachiLui.)