Remembering Karl Wallinger: The Late, Great Visionary World Party Bandleader Discusses His Love of Vinyl, and He Shows Us How He Double-Tracked Vocals Only by Using an Album Cover

Eleven days ago, we lost another good one. Karl Wallinger, the visionary bandleader, singer, songwriter, composer, and all-around sonic Svengali of the alt-pop-leaning British collective known as World Party, sadly passed away on March 10, 2024, at the still young age of 66.

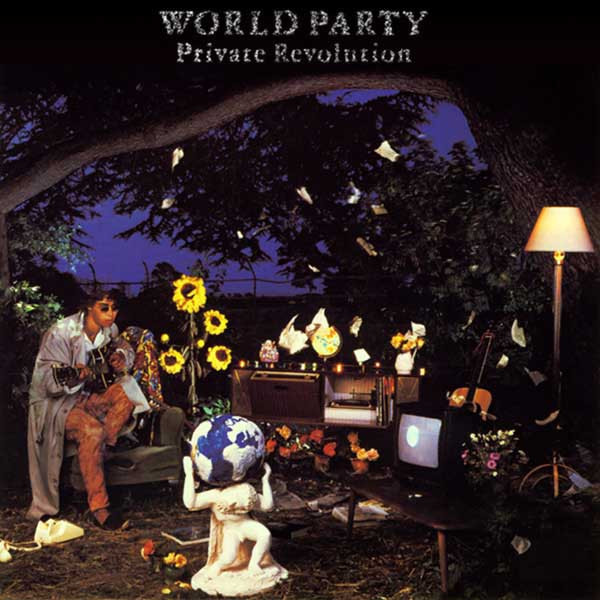

Known for catchy, cleverly arranged, and cunningly written songs such as “Ship of Fools,” “Way Down Now,” “Put the Message in the Box,” and “She’s the One,” the Welsh-born Wallinger built on his Beatlesque-influenced recording inclinations by forging his own brand of album-oriented tracks (and tracking) that began with World Party’s 1986 debut LP on Chrysalis, Private Revolution, and continued on intermittently up to October 2000’s Dumbing Up, on his own Seaview label (though other vault-culled WP releases have also ensued between then and now).

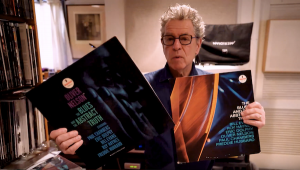

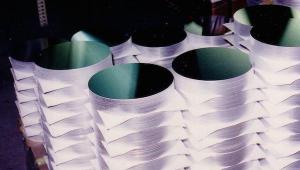

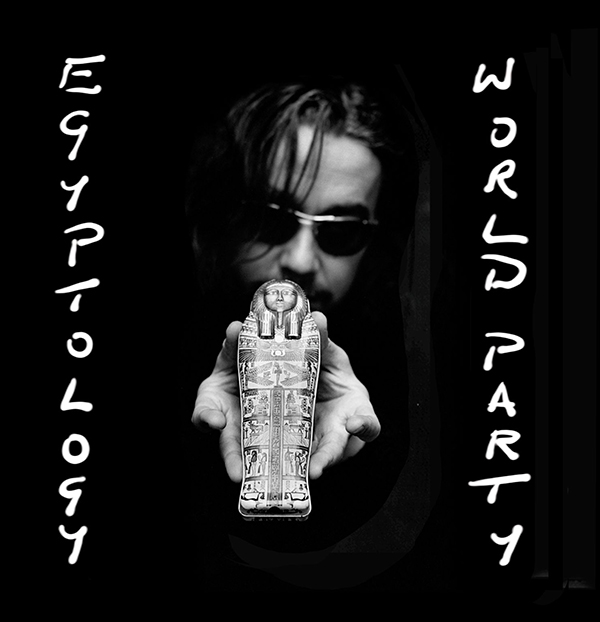

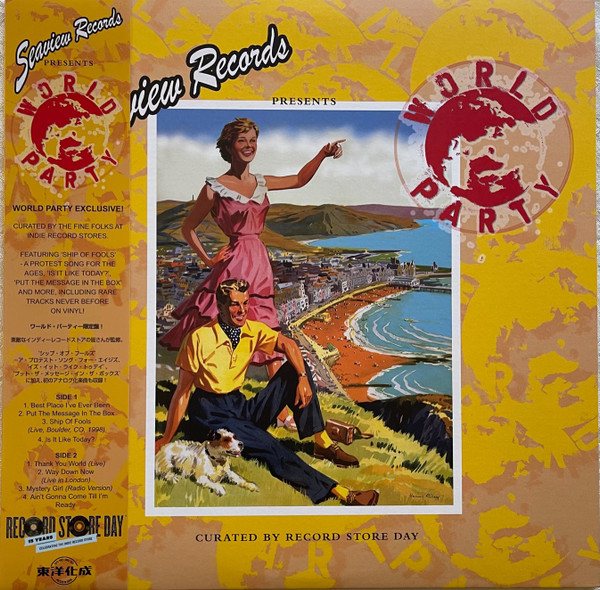

In later years, Wallinger began reclaiming his recorded legacy from the Chrysalis and Ensign label imprints by intermittently reissuing WP’s entire five-album studio catalog on his own aforementioned custom label, Seaview Records. Four of those LPs (Private Revolution, Goodbye Jumbo, Bang!, and Dumbing Up) have appeared as 180g 1LP sets pressed at RTI (each of them with respective SRPs of $24.99), while the fifth, Egyptology, was expanded into a 180g 2LP set pressed in the Czech Republic (on purple and gold vinyl and sporting an SRP of $34.99, with Side Four featuring five unreleased live tracks). And for Record Store Day in 2022, the 1LP, 8-track release Seaview Records Presents. . . World Party – Curated by Record Store Day (with a median SRP circa $25.99, and limited to 2,000 copies) is comprised of a trio of known favorites, four live tracks, and an alternate radio cut — plus, it comes with an OBI strip, was manufactured In Japan and issued for RSD worldwide, and you can still order it via the Record Store Day Marketplace, a.k.a. RSD MRKT, here. (The balance of the other WP titles can be ordered here, as well as by clicking on the Music Direct graphic shown at the end of this story.)

Wallinger and one of his right-hand production mates, Tim Young (whose name usually is preceded in the credits with an “edited, mastered, and remastered by” distinction), clearly took extra care with each WP LP re-release, making sure the band’s analog-inclined content — Wallinger loved using tape whenever he could, even in the modern age — truly lived and breathed on 180g vinyl, without sounding digitally induced or compressed, regardless of any digital-oriented production steps.

My own recent WP-on-vinyl refresher course taken through the entire catalog on Seaview proves the point, as songs like the aforementioned “Ship of Fools” (Side One, Track 3 on Private Revolution, with its supportive piano vamps on the verses, supple but not intrusive bass line, Anthony Thistlethwaite’s sax accents, and the “save me / woo-hoo-oohs” layering on the choruses) and “Put the Message in the Box” (Side One, Track 4 on April 1990’s Goodbye Jumbo, with its layered vocal harmonies on the choruses, the clarity of the alternating right-channel shaker and tambourine percussion elements on the verses, and the “ahhh” vocal bridge) each show how this music was made with the needle-drop in mind.

While I’m at it, I should also give positive aural props to the analog acumen of the following four WP tracks: 1) “Is It Like Today?” (Side One, Track 2 on April 1993’s Bang!, with its wide, wide stereo field, clear acoustics, gritty-to-tender lead vocal, and intentional — or not — nod during the outro to the slowed-down car-horn battery intro [circa 0:08 to 0:13] of Van Halen’s “Runnin’ With the Devil” on their self-titled February 1978 Warner Bros. debut); 2) “Rolling Off a Log” (Side Two, Track 5 on June 1997’s Egyptology, with its orchestral Wall of Sound construct, lost movie soundtrack vibe, occasional strategic volume swells, full-on “ahh-ahhs,” and dramatic gong hit near the end); 3) “Always on My Mind” (Side Four, Track 4 on the above-noted Dumbing Up, an 8½-minute prayer elegy with a going-to-church feel, clear piano and keyboard wash behind Karl’s Dylanesque testifying rhyming scheme, and full liberation choral moments); and 4) “Mystery Girl” (Side Two, Track 3 on the Seaview Records Presents RSD LP, which is stripped down from the more horn-driven version on Disc 5 of Arkeology here, with just-right brush drums and acoustic guitar accompaniment — très magnifique!).

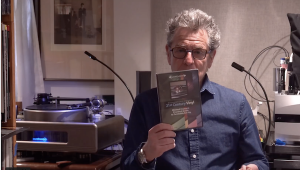

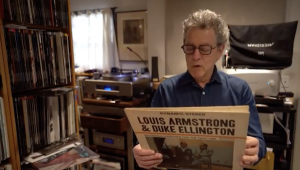

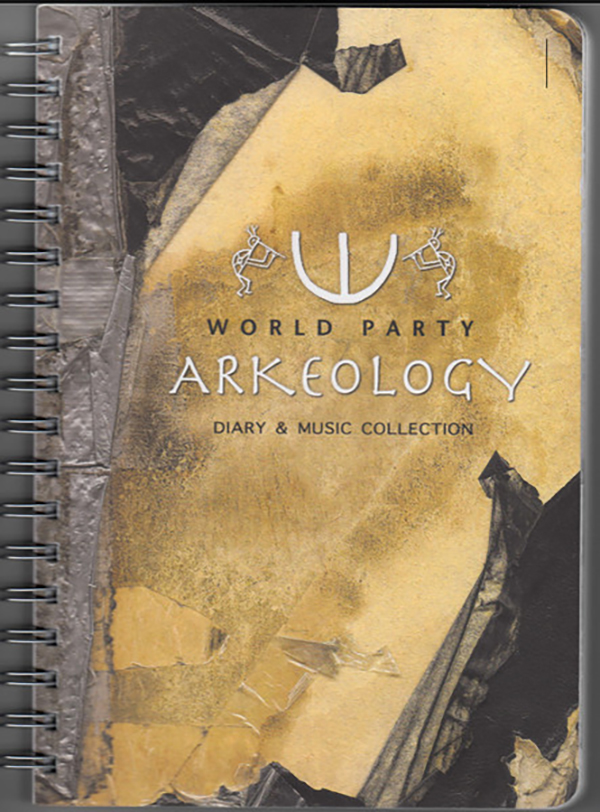

As is sometimes the case, of the two-plus hours I spent with Wallinger in a midtown Manhattan bistro café on May 1, 2012, with the impetus to discuss his then-new — and innovatively designed and presented — self-released, 70-track, 5CD Arkeology – Diary & Music Collection spiral-notebook-sized compilation (replete with an illustrated, full-year daily calendar therein, no less), the interview was essentially boiled down to a few select quotes that were intended as a precursor to a larger story that never quite materialized after that. Once I learned of Karl’s passing 11 days ago, I dug into my files to find the original recording. Not only did I locate the audio with limited hassle, I also came across five minutes of semi-forgotten, unedited MP4 video footage of the two of us talking mostly about vinyl that was self-shot on a DTS-branded Flip Cam (remember those?). Although not perfectly framed — hey, it was a one-man, on-my-own afternoon wherein the best option I had before me to film it was to center the pocket-size black-and-silver Flip Cam carefully atop a stack of CDs and magazines that I had perched on a raised bar chair.

Regardless, this video content itself is indeed a found blessing, especially the sequence after our brief, introductory Arkeology talk when Wallinger demonstrates his own DIY double-tracking technique by utilizing the album cover of my original LP copy of Private Revolution. Without further ado, here is the world premiere of said edited video (with thanks to my compadre Ken Micallef), which has also been posted on AP’s official YouTube channel for one and all to enjoy. (Bonus points to those of you who — without Googling or Shazaming! — know which WP song Wallinger sings a brief snippet of here to demonstrate this technique. Feel free to chime in with your own educated guesses in the Comments section that appears below, after the end of the Q&A portion of our interview.)

Speaking of Arkeology, at one point, and while classical music was unendingly pumped over the bistro’s in-ceiling speakers as we sat and chatted that day, I asked Wallinger if he’d consider releasing this gem of a rarities collection on vinyl someday. “I’d love to do that. I’d love to do a 10-album box set of Arkeology, yeah,” he enthused. “I mean, I did this thing [holds up my copy of the actual Arkeology calendar notebook] at home on the table in front of the TV in the living room (laughs), and I’d never seen anyone do one in a diary format like this. It’s an attempt to insinuate myself into everyone’s lives. (laughs again) I just thought, ‘We’ll make something which is basically an analog product, because even if you get it online, you’re not getting the whole thing.’ But, yeah, maybe someday we can do a vinyl box set.” Incidentally, Arkeology, if you can even find it out there, goes for a pretty penny on the collector’s market these days. For example, the lone copy listed on Discogs as of this posting goes for a little over $271 U.S., sans shipping.

Mulling over the idea of putting out the contents of Arkeology on vinyl a bit further, Wallinger mused, “I think it would be about 12 discs, actually. It would have to be more than the 10, because I think every CD is slightly longer than a double album kind of thing. Or maybe we could release it as separate albums in some kind of series. That would be nice — or maybe we’d do a reduction to a double album that leaves out the cover [songs] or the live stuff, and just have the original songs that haven’t been released before. There are a few ways of going with it.” (Note to the executive team at the hopefully still-going Seaview label: If you’re able to follow Karl’s wishes here in any vinyl capacity, we’re all ears. . .)

Wallinger and I spoke about more than Arkeology that day in May 2012, of course, so I went back through the audio so I could share with you the balance of Wallinger’s analog-centric thoughts on the importance of how to properly sequence song cycles on LPs, why he once wanted to open his own record store, and his early proclivity for listening to progressive artists like Yes, Pink Floyd, and ELP on vinyl. Ain’t no who, what, why, or when / Gonna turn me round from this world. . .

Mike Mettler: Earlier, you told me you felt Arkeology is, quote, the “closest thing to being a new World Party record that I’ve come across” — so, of course, I’d like to zero in on the word “record” for a moment here. I’m just curious as to whether the full album-on-vinyl concept is something that’s still important to you.

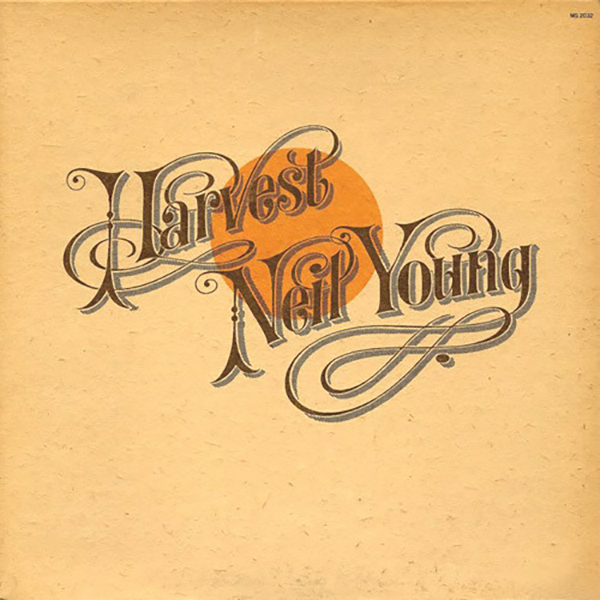

Karl Wallinger: Yeah, I think it is. I mean, however hard I try, I can’t forget the effect that those records I loved had on me. Listening to Harvest [Neil Young’s February 1972 masterpiece, on Reprise] was an experience that had an integrity to itself, which is beyond the individual tracks kind of thing. It’s very difficult really to say, but I don’t like the world to turn into a jukebox where you just select a song, and then another song, and then another five.

There definitely is something about the contrasting from one track to the next. There’s something in the sequence of songs that can be as meaningful as the individual songs themselves. There’s some journey there that is a valid one that you do go on.

Mettler: It’s funny you say that, because Jakob Dylan and I talked about that very same thing a few years ago where he said, basically, “I take a lot of time putting these songs in a specific order, because even if Song 4 is not directly related to, say, Song 7, it informs how you get there — and I really want you to get to it in that way.”

Wallinger: Yeah, yeah. A song cycle is how I think of it, really — and that’s been going as a format for many years, since way back into the 16th, 17th century. The whole idea of just this MP3 that you download of one track, and that people don’t want the other stuff anymore — it’s like, “Hmm, I don’t know.” [MM adds: For context, recall that this was a pre-streaming-era interview, hence Karl’s MP3/download reference.]

Wallinger: It's a crazy thing. It’s a whole format that’s just got its own reaction. I mean, I used to sing — there was a particular technique I had of using an album cover in front of my face that made my voice sound like it was double-tracked.

Mettler: Oh yeah? Well, you’ll have to show us how you do that. Would you do it on video?

Wallinger: I would do that on video. I could show you how it works, because it’s quite amazing.

Mettler: Great, we’ll do that after we’re done with the interview. You know, we always seem to remember how much those early singles and albums affected us, right? And then we try to recreate the feeling somehow either by listening, or creating.

Wallinger: Yeah, yeah. It’s like old photos, or something of your upbringing. You feel like you know them — they’re like friends. I think vinyl is a great format. It’s just what it was and the limitations were as they were, and it created this kind of artform that was a known-entity sort of thing. The fact that it’s not transferrable, or very difficult to duplicate, is another plus to it as well.

It’s almost quite strange, really, to be that involved with the music. It’s like, “Oh my God, I’m really listening to a record.” I’ve really missed it as a format. I love the idea of it — I mean, the other day, I just wanted to open a record store. Just a record store and a counter with decks on it, with two pairs of headphones and two swivel chairs in different positions alongside. And a sign: “We only sell records. We don’t sell anything else — not cassettes or CDs or books, or anything. It’s just a record store.”

I really wanted to have that experience of walking through a record store again, and just looking through the bins . . . (pauses, sighs, and smiles) Oh, it was just amazing. And it is growing by a percentage every year — the amount of people listening to vinyl.

Mettler: It sure is growing. Besides us elder statesmen (both laugh), I’m glad the younger generation is getting into vinyl now too. You mentioned Neil Young’s Harvest earlier. Was that the first album you actually bought that you remember being the very first one you were really excited about owning and playing?

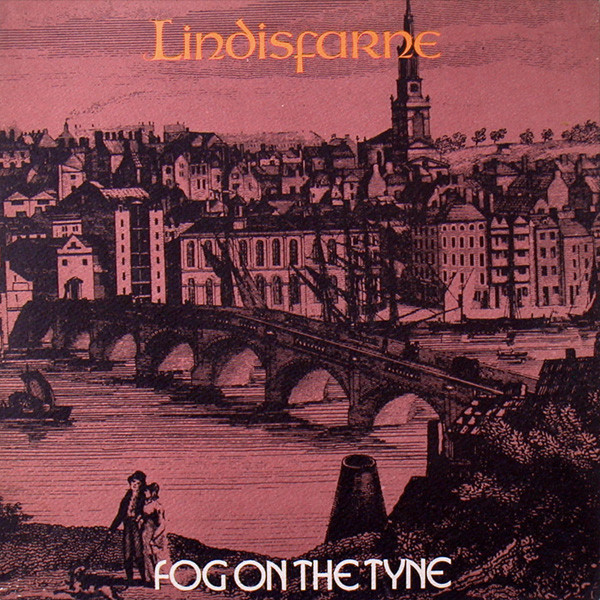

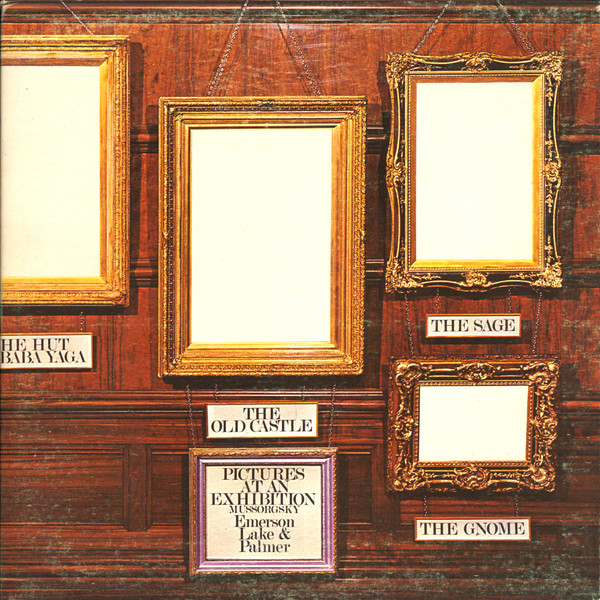

Wallinger: Album-wise, it must have been — I think I bought two at the same time. It was Harvest, and [Lindisfarne’s] Fog on the Tyne [released on Charisma in October 1971]. And maybe after that, it was Pictures at an Exhibition by Emerson, Lake & Palmer [released on Island in November 1971].

Mettler: Wow. That’s an interesting mix, right there.

Wallinger: Yeah, it was! And I just re-got Fog on the Tyne recently, actually. It’s a great record, and they were great, Lindisfarne. Alan Hull, I thought, is sadly missed, actually. [Lindisfarne co-founder and singer/songwriter Alan Hull passed away at age 50, in 1995.] He played with John Turnbull, [a British guitarist] who I’ve worked with many times over the years. John’s from up there too [Newcastle upon Tyne], and he was 15, a real young kid, when he came down and emigrated to London to play the electric guitar, but he used to play with Alan Hull. I really had a soft spot for that Tyne record. I loved it.

And the Neil Young Harvest album — it’s like an amazing, beautiful thing, with that bass, and the bass drum. It’s just a great album. I mean, how do you write songs that aren’t really about anything, and yet they seem to be the most profound statements the world’s ever known, you know what I mean? It’s this strange, strange ability he’s got to make words like “but I knew” seem like he’s like describing God, or something. The tone, the quaver in his voice — ohh, it’s such a beautiful thing. It’s timeless.

And the ELP one [Pictures at an Exhibition] — I suppose it’s the keyboard thing. That was the attraction for that one, and there’s a track on there which was this synth thing (mouths Keith Emerson’s main synth line on “Promenade,” which appears in three separate parts on Pictures). Yeah, it was this crazy track, and it was the time when everybody used to sort of freak out and throw themselves around the dance floor, so it was suitable to gyrate to like that. Pretty strange. Looking at them now, they just look ridiculous — but at the time, it was quite fun. And I can own up to liking them! (laughs heartily)

The keyboard thing always interests me anyway. The Rick Wakeman stuff, and the work he did with Yes — I used to love Yes. [February 1971’s] The Yes Album, [November 1971’s] Fragile, and [September 1972’s] Close to the Edge. And I used to trip out to [Tales From] Topographic Oceans [released in December 1973 on Atlantic, the same label the previous three Yes albums he mentioned were], which was pretty crazy. Maybe that didn’t do me much good (chuckles), but at the time, I had this great Farfisa — and now you know how everything went wrong. (both laugh) No, but the Farfisa Compact Duo, which the [Pink] Floyd used to use, I used to have one of those in this basement in Godalming, in Surrey.

Mettler: Oh, I loved what Rick Wright did on the Farfisa with Pink Floyd on [their March 1967 EMI/Columbia single] “Arnold Layne,” [July 1968’s] A Saucerful of Secrets [on EMI/Columbia], and most especially on “Echoes” [the epic 23:30 track that takes up all of Side 2 of November 1971’s Meddle, on Harvest].

Wallinger: Oh, I loved all that too. Loved “Echoes.” To me, definitely both [September 1975’s] Wish You Were Here [on Harvest/Columbia] and Dark Side [i.e., March 1973’s The Dark Side of the Moon, on Harvest/Capitol] are seminal records — and that’s it, really. After that, I kind of started to yawn, and fell out of interest.

But I do love [David] Gilmour’s guitar — the things he can do with just one note can be so meaningful. I also love Neil Young’s lead guitar. I love the one-note guys more than the super-speed guys. I’ve always loved the sort of personal, “I’ve got this great note here” (vocalizes one sustained note), rather than (vocalizes a fast fretboard run). Never dug it. Me, I just play in G, and I’ll see you at the end! (both laugh)

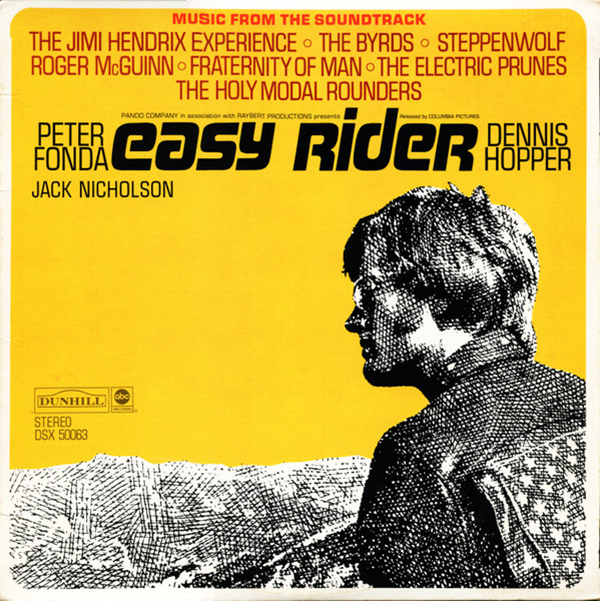

Wallinger: Growing up, I also remember we had the Easy Rider soundtrack [released on Dunhill/ABC in August 1969]. Which is what we had, like a random album — and when you’re at the family home, you’ve got like 20 LPs. One of them’s [1957’s] West Side Story [on Columbia], one of them’s the Easy Rider soundtrack — and these two things become massive for you, because they’re not only great, but they’re there.

And the Easy Rider soundtrack was — well, it’s got [The Jimi Hendrix Experience’s] “If Six Was Nine” on there, and it’s just amazing. There are lots of songs on there that are just superb, and humorous, and indicative of the time. It’s a great little collection, with [Fraternity of Man’s] “Don’t Bogart Me,” and the whole thing. So, there’s comedy, but there’s also [Steppenwolf’s] “Born to Be Wild” and “The Pusher,” which are just two great tracks — and the guitar [by Michael Monarch] still sounds amazing to this day. Unbelievable, just unbelievable.

That was maybe a funny album to be listening to, but these things, they just take on this mad sort of — they inform you, and it’s like a strange, quite random stamp. There was that, and then artists like Bruce Channel [a one-hit wonder with “Hey! Baby,” a No. 2 single in the UK in 1962 on Smash, and a No. 1 in the U.S. on Le Cam], and all kinds of other weird things. I used to stack them up on the arm — you know, 10 singles. I used to do that all day long, with all kinds of things from Lonnie Donegan to Jimmy Smith.

Mettler: You still work with tape, don’t you?

Wallinger: Yeah. I still chop up two-inch [tape], and that’s pretty good. I mean, I use all formats, basically, but I’ve taken to recording everything onto two-inch, and then dropping the whole reel in at the same time — into the computer. And then you can do overdubs in the computer, or you can do overdubs with it synced to the tape, and then back on the tape again.

That seems to work pretty well as a modus operandi, because you have the rewind. I love, when you’re tracking, having rewind time to sit down and take a break — but with a computer, you just sort of stop, play, and go, “Oh, we’re playing it again.” It’s a bit too heavy duty, but I like those couple of minutes of rewind time just to light a. . . (pauses) or roll something else amazing that you need. (smiles)

Mettler: I’m sure you’re referring to, uh, amazing vinyl there, right? (more laughter) Anyway, I know I continue to be amazed by how connected I feel to music I play on vinyl, especially if it’s an older record I’m either playing again or when I’m cueing up a remastered or reissued version of one.

Wallinger: That is a great thing, and I rely on that — those ideas, the same ideas I had when I was like seven or eight with those records. I trust those feelings. I try to cast off the other kind of constructivism or things that have informed me. I try to be as natural as I can with the whole thing — and I like that. That’s where I try to be when I’m making the music.

I don’t — I try to be as unconscious as I can be retaining the power of the movement (indicates receiving information/inspiration from on high), and that’s about the limit, because I don’t wanna be thinking about this music. The best things happen when you are not in control of it. You aren’t saying, “Well, we’ll have this here and that there, and it’ll all be fantastic.” I don’t know what is fantastic. I know that you can get lucky sometimes, and what you get with it is something fantastic. But it’s nothing to do with you — and don’t you try claiming it. (smiles) Most of these songs, I can almost not really claim to have written them in a way, you know what I mean?