Sir George Martin Interview Part 2

MF: For the most part, you chose the material; it was only a few people who…

Martin: Pretty well, pretty well. I mean the idea of Vanessa Mae doing "Because": The idea of a mini violin concerto came first, and I had to find someone to play it.

MF: But she put so much into that. Sometimes that kind of thing doesn’t work—when you try to “classical-ify” something. But that was very good.

So aside from the Beatles, who were the most memorable artists that you’ve produced? Any standouts?

Martin: Any other artists? Well, I’ve been so lucky to produce so many people. It’s difficult to name one. It’s like saying, what’s your favorite track? Obviously, Peter Sellers comes pretty high on that list. We worked very well together.

MF: And that’s what led you to do the Billy Connolly track?

Martin: Well, don’t forget, I did record "A Hard Day’s Night" with Peter Sellers. Did you ever hear that?

MF: No.

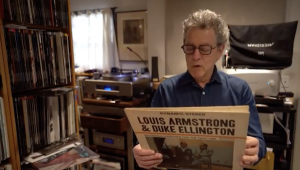

Martin: I also recorded "Can’t Buy Me Love" with Ella Fitzgerald. Did you ever hear that?

MF: That I’ve heard. And I’ve also heard her do a Cream song, "Sunshine of Your Love." That was just—wow! [both laugh]

Martin: "Can’t Buy Me Love" worked very well, I thought. We did a number of Beatles’ tracks with Peter.

MF: He was fantastic.

Martin: But also, people like Matt Monroe, who was a great friend of mine, and I made lots of albums with him. He had a fine voice with a fine delivery. He was kind of England’s Sinatra, if you like. What was against him was his looks: He was very small and quite pudgy. He wasn’t the sort of clean-cut American hero that you want…

MF: He wasn’t dashing…

Martin: He wasn't dashing, but he was a great singer. I loved working with him. People like—oh, I don’t know, like John McLaughlin. I loved working with him. I’ve worked with so many good people.

MF: I'd like to ask you about some specific Beatles songs. But before I get to that: Were you aware early on that Capitol was taking your recordings and messing around with them and adding reverb?

Martin: I found out about it, yeah. Oh, I was very upset about that. Capitol did some terrible things. It still riles me to this day.

MF: And you couldn’t stop them?

Martin: I was reading a report in one of the papers about the days of Capitol and the “brilliant” Alan Livingston who, amongst his many achievements, "signed the Beatles." And that made my blood boil--because he was the one who rejected the Beatles time and again, after I got them and was trying to get them released in America. He kept saying, “You don’t know the American market, George!” Eventually, when the tide of opinion was too overwhelming, he reluctantly put out "I Want to Hold Your Hand"--and then kept it for himself. And they were now “his boys.” Oh, I couldn’t…!

MF: And then they messed around with all the records!

Martin: Well, that wasn’t his doing. [laughs] But then the first album comes out as, "Produced in America by Dave Dexter." Well, what the hell did HE have to do with it?

MF: He just ruined the sound, basically--or tried to ruin it the sound. How could they have the license to just take it and do what they want with it?

Martin: They just did. They didn’t have the license to do that.

The other thing—and this has become history now—was that they took the twin-track records which were mono recordings and issued them as stereo.

MF: I want to talk about that. One of the things I’m curious about is—and what got me into trouble with some reader--is the story of "Baby, You’re a Rich Man," "Penny Lane," and "All You Need is Love." I guess Eddie Kramer recorded those at Olympic….

Martin: Was it Eddie Kramer?

MF: He said it was.

Martin: I thought it was Keith Grant. Certainly, we did "Baby, You’re a Rich Man" at Olympic. And we did the basic track of "All You Need is Love" there, but that was it. We did the rest of it at Abbey Road.

MF: Eddie Kramer came over to my house to listen to some Hendrix things he was doing—which was a thrill for me, as you can imagine—but he’d never heard it in stereo. He’d only heard what Capitol did to it. And I had written something in The Tracking Angle that said, “Why did Capitol take what George Martin must have sent across as a mono track, a mono mix, and why did they electronically reprocess it and ruin it?”

Martin: First of all, I didn’t send over anything.

MF: So how did that happen?

Martin: The process was that I would do my masters in England, and they were going to be bought and that would be it. And then Capitol would send over for the masters. And they, unknown to me, would get, in some way, the masters before they were transferred. Now, in the early days we didn’t have multi-track recording...

MF: Four-track?

Martin: Four-track was the earliest thing we had and that wasn’t until 1965. From ’62 to ’65 we didn’t have four-track. We had mono--mono was the thing. Mono was all that pop records were. Stereo was reserved for classical. Stereo wasn’t considered to be in any way useful to pop record because it dissipated the sound...

MF: ...on the radio...

Martin: ...and pop had to hit you square on the nose. And so it was considered irrelevant. Very few people had stereo machines anyway. And if they did, they generally had them in cabinets where the speakers were about a foot apart, so you couldn’t really tell.

So mono was the thing. But I took a stereo machine and separated the tracks and made it into a twin-track machine. So when we recorded the Beatles live as we did, we didn’t overdub. I would keep the voices on one track and put the backing on another, so when they went home I could then mix it down and keep the voice forward--but at the same time get plenty of impact. I wouldn’t have to do it on the spot. So that gave me time.

MF: And there was some leakage between the two tracks because they were playing live...?

Martin: Of course.

MF: But it was amazing separation!

Martin: Yes, but then, in the instrumental where the voices stop, all the shit comes out on that track from elsewhere. When I first heard what they’d been doing, I was horrified. But they just did. And I didn’t find out 'till afterwards, and it was too late.

But the worst thing is: The people got used to this and loved it! They liked to be able to turn up the voices in songs. So I was hoisted with my own petard here. I couldn’t protest anymore. I was saying, “Why do you do this? It’s a travesty!” But then they’d say, “The people like it!”

MF: But that came out in England also—the stereo With the Beatles.

Martin: It did. By this time I’d left EMI, and I had no power there at all. I left EMI in 1965 to start my own company. Up to ’65 I was the head of Parlophone Records, so what I said went--as far as Parlophone was concerned. But once I left, I had no authority...apart from complaining.

MF: Back to those Capitol tracks: They were in mono, I assume.

Martin: Yes, "Baby, You’re a Rich Man," "Penny Lane," and "All You Need is Love" should have been mono.

MF: We know Capitol was electronically reprocessing your recordings: taking the highs out on one side and adding bass to the other, so you were left with two bad mono tracks. What I can't understand is, why were they mixed to mono to begin with--and how did the Germans end up with stereo mixes of it? That’s what I can’t understand: On the German records, those three songs are in real stereo, with a good mix.

Martin: I don’t know. I don’t know the answer to that. "All You Need is Love" was four-track...

MF: And "Baby, You’re a Rich Man" and "Penny Lane" must have been also because--

Martin: "Penny Lane"? [pauses] Yeah, I guess it must have been…

MF: The mixes are incredibly good.

Martin: This is not like the fake stereo thing we’ve just been talking about?

MF: No, it’s a well-panned, well integrated, really good sounding thing. I played it for Eddie Kramer, and he was just blown away by it.

Martin: The first four albums are still not available in stereo officially, are they?

MF: Not as reissues, no. So basically you didn’t remix those tracks? Do we know who mixed them?

Martin: I might have done that. I might have made a stereo job for ourselves, which wasn’t issued. We quite often did that.

MF: Yeah, somebody got hold of that and issued it in Germany. Then it came out here on cassette, of all things.

Martin: Again, you see, people talk about Sgt. Pepper's, which was four-track, and the stereo and the mono versions of that. Well, when we finally put the album together in April ’67 or whenever it was, the tracks were mixed with the boys in mono.

MF: And those were the ones that counted.

Martin: That’s what counted, yes. And we spent three weeks mixing Pepper in mono with the Beatles present. Then the Beatles went off and disappeared. Geoff Emerick and I spent three days mixing the stereo. And that was it. The Beatles never had any input in that. But the stereo has now become the final word.

MF: So why won’t they reissue that in mono now? People want the mono.

Martin: Well, they should have it. But these are all record company decisions. And it’s marketing—it's nothing to do with me.

MF: I did a radio show with some people a few weeks ago—an all vinyl Beatle radio show—and they played all these weird things like an American version of "I’m Looking Through You" with a couple of extra bars of guitar intro that the British version doesn’t. How does that kind of thing happen? How do they get that?

Martin: I don’t know. [chuckles]

MF: And then there’s a Dutch pressing of "All My Loving" where Ringo counts off on the hi-hat: only on that record! There’s no explanation for how these things happen.

Martin: Well, except that they might have got the raw masters. When I finally tweaked them on final issue, I might have cut out bars. I might have taken off the fronts of things. But I still left them on the master track. If they then took the master track and issued them….

MF: So they wouldn’t have used the LP master, they would have had to go back and…

Martin: They would go back to the vault.

MF: And these were open to people to do this?

Martin: No--it was quite wrong! They shouldn’t have done. They should have asked my permission, but they never did. I think if I’d been an executive of EMI, it might have been different than that. But the Beatles at that time weren’t sufficiently strong.

MF: Even by then?

Martin: Because they were so fragmented. I mean, don’t forget, Brian Epstein died in 1967. And they were in the wilderness for a while. It’s only since they set up Apple that they’ve been really tough on all things. And for twenty years now, they’d paid a guy a lot of money to say "no" everywhere.

MF: Would it surprise you if I told you that, sitting down in my listening room, comparing my thirty-year old Parlophone LPs with the CDs that came out a few years ago, that everybody thinks the original 30-year-old records sound better?

Martin: I expect that.

MF: What are the chances now that we can go back and do another round of transfers either using 20-bit technology…

Martin: We could do...

MF: …and 96K? I have 96K/24-bit recordings at home. Or what about Nick Webb cutting one more set of lacquers for the people that like records? Shouldn’t that be done?

Martin: We could do that. It could be done. Of course it can be done. But will it? I don’t know. These are all commercial decisions.

No, it has nothing to do with technical possibilities or aesthetic desires: This is to do with the bottom line. This is to do with stock control and whether there’s room in market for another bit of product on the shelves, whether we’re gonna sell enough--all that kind of stuff. Which is nothing to do with me. I have no control over that stuff.

MF: People are clamoring for this.

Martin: Well, would they buy in sufficient quantities?

MF: I know the Hendrix Estate decided to release vinyl of all the Hendrix issues. They keep pressing them and selling them. It’s like a license to print money. They press ‘em and they sell ‘em. They can’t keep up with the demand. That’s in the tens, fifteens, twenty thousand numbers—which is not a lot, but they sell them for thirty bucks a piece. And they’re doing well.

Martin: I think they may do, but at the moment I think they’re in a kind of waiting period. Every now and again, they do something and come in with reissues and things...

MF: Geoff Emerick brought the master tape of Sgt. Pepper's to New York a few months ago, and I was invited to come over and listen to it, because I helped him get a Studer C37 to play back on...

They played back the master tape for me and I sat there and--you know, that experience, I’ll never forget what that sounded like. That was just awesome. And I know with 96K/24-bit, people at home with DVD players can hear them just about like that. And I hope it happens.

I sat down and I watched the laser disc of the Anthology, eight laser discs, the other day. It took a few days actually to sit and watch it. And when it was over I sat there and I realized that, despite everything I’d seen and all the explanations for everything that were given by you, by other people, I still can’t explain what happened there for those six or seven years. Can you explain it?

Martin: Their whole phenomenon...?

MF: The whole phenomenon. You know, today, in the last twenty years or so I think a number of artists have come along, at least for my tastes, that had the potential to do the same thing, and it’s a matter of the audience putting into them what they give the audience, and building on this kind of feedback. I think Andy Partridge and XTC had that potential: It never happened...

So what happened?

Martin: I think it was an extraordinarily fortuitous combination of talent. If you think about it, you get from time to time—and I’ve seen it many times—you have a young man coming along with a raw, uninhibited semblance of something there. To begin with, it’s pretty rough, and no one takes much notice. And he perseveres with it—in any field—and he comes through and he starts shining. And this was true of the Beatles.

When I first met them in ’62, their material was terrible. Their songs were...I mean, "One after 909"? What the hell was that? It was silly stuff. Not very good, really. But they had this potential, and they had this charisma. John Lennon and Paul McCartney were two individuals: very alike, but creating rather different kind of music. And if you’d got one of those in any lifetime, you were lucky. But here you had two of them working together. And the third guy called Harrison who wasn’t bad either. They had a rough drummer who they got rid of. And then we had another guy who was a much better drummer and also something of a quirky personality with a good talent for one-liners. And suddenly it becomes a group, who within the first few months of their working in the studio realized what it was all about, did their homework, learned a lot, studied how to write a good song, and then came up with the goods. And they had this fervent belief in themselves, that they were going to make it.

MF: The time and the audience were right, too. You know, there are people here that postulate that it had something to do with the Kennedy assassination. You've heard the theory: that people were so depressed and so down and so upset by that, that when these four guys came along with the whatever they exuded, that people just--

Martin: Yeah. I mean, I saw it happening—first of all in England. We started making records in ’62, but we didn’t make our first Number One until the early part of ’63. And all through ’63, I said to them, “Okay, that was good what you just did, but you can do better. Come back and give me another song better than that.” And they would. They’d come back and give me another song which was better—and different. They never did the same thing twice. They never gave me Star Wars II. They always gave me another song, another spark. And I would take it gratefully, wondering how long it would last. And it did last. And then eventually after being turned down like St. Peter three times or saying no three times, we finally got Capitol to issue "I Want to Hold Your Hand."

MF: Well, because the small labels grabbed it and made something happen.

Martin: In the meantime, the small labels had been building up the excitement. And we were already well established in England, and the fans from England were terrific. The boys were by this time on a roller coaster of success, and they were loving every minute of it. They’d finally made it; they’d finally got their dreams coming true.

MF: It had to be much more intense than what their dreams could have been. I mean, the whole thing had to be much bigger than what they could have dreamed.

Martin: Well, we talked about this a great deal. They weren’t going to come to the States until they had a Number One record there. And I said, “You’re arrogant little buggers—you always were!” And they said, “No, there’d be no point. Because if we go there and flog ourselves, it’s been done so many times in the past, it’s not going to work.”

And I was with them in Paris. We were recording for the German market, and they were appearing at the Olympia and they were staying at the Hotel George V—I wasn’t staying there! I couldn’t afford it! I was at another hotel around the corner. And very late at night, I was in bed. And Brian rings me up: “I’m sorry to wake you, George, but I know you won’t mind being woken.” I said, “Well, what is it, Brian? What on earth…?” He said, “I’ve got to tell you: We’re Number One in America!” And I said, “WOW!!!!!!!!!” “We’re going to celebrate! Do you want to come 'round?” So I put my clothes on and we went around to the George V and had a great party. That was the first time we knew what this meant.

And then they went to America of course, on The Ed Sullivan Show and all those kinds of things. I went with them and I saw them. I was here [in New York] at the Plaza. I saw the whole town was taken with them. People in England could never believe what happened. No matter where you turned your dial on the radio, at any time of the day, everywhere was a Beatles record. It was complete saturation. Men of my age now were walking down Fifth Avenue with wigs on their head, saying [affects American accent] “Hi! I’m Ringo! Who are you?” [both laugh] It was madness. Outside the Plaza, you had bout five or six hundred people. It was jamming traffic...

MF: I remember that myself. I was in high school when "She Loves You" came out. At that point, I’d given up on rock and roll. I was listening to jazz and smoking a pipe. [laughs]

Martin: And trying to be grown-up.

MF: Yeah, because Fabian and Frankie Avalon, rock 'n' roll—I’d outgrown that. But I’ll never forget the day: It was one of those days that you just don’t understand. I was in a car, and it came on the radio for the first time, and it hit me. I mean, it hit me hard. And it changed my life--but I still don’t understand it.

Martin: It was an extraordinary blossoming of talent. What was more extraordinary, I think, was that it metamorphosed from that early excitement into something really worthwhile. If you look back at it, they were terribly exciting little, little songs, but they weren’t exactly Schubert. But then they did become exactly--almost exactly--Schubert. They metamorphosed. They started growing—growing in their stature, and they started writing really good stuff. That was the most surprising.

It was a combination of several things, several people. And it was like putting in the elements of a nuclear explosion: You have to have them all at the right time, all the right ingredients