Of course I did. But I haven't read it since 1999 so it read as if someone else had written it so I enjoyed the read as a third party. Very weird feeling.

Analog Corner #42

(Originally published in Stereophile, January 12th, 1999)

Politics and audio don't mix! Keep your pinko ideas to yourself. I cancel my subscription!"

How many times have we read that in Stereophile, shortly after a writer has injected a few cubic centimeters of ideology into a review or column? No doubt all of the offended parties dashed off equally angry letters to ultra-partisan House majority whip Tom (the bug exterminator) DeLay, who threw a hissy fit back in October when he found out that the EIA (Electronic Industries Alliance, the parent organization of CEMA, which runs the Consumer Electronics Show, etc.) had the gall, the nerve, to hire former Oklahoma Democratic representative Dave McCurdy as the group's president and industry spokesperson.

The appropriately named Dick Armey and a few other prominent Republicans joined DeLay in their outrage over the private lobbying organization's choice. According to the New York Times (October 14, 1998), they went so far as to contact the EIA's board, in an attempt to exert pressure on it to reject McCurdy's nomination. The board ignored the political interference and hired McCurdy, but not before Michael Scanlon, an aide to DeLay, said ominously, "To hire a Democrat to represent this group before a current Republican majority, and what is certain to be a larger majority, is not a shrewd business decision."

Can you spell "political extortion"? I find that behavior far more odious than Bill "should a man offer a lady a Tiparillo" Clinton's transgressions.

Fortunately for me, I was out of the country when the prez's deposition in front of Ken "I'm against pornography, but wait'll you read this stuff!" Starr was made public. I was in England covering the hi-fi show I reported on in the December issue, and paying a visit to Rega's manufacturing facilities at the invitation of Rega's US importer, Steve Lauerman, who was taking a group of US dealers to the UK.

After two days of Indian food and hi-fi at The Hi-Fi Show 98, Lauerman and I headed for Camden Town to do some record shopping before taking the train out to Essex town Wickford, where Rega principal Roy Gandy was to meet us. Camden Town is in the northern, "working class" part of London; I was struck by how the clean, modern train that whisked us from Heathrow to central London was replaced by a decrepit, ancient, wood-trimmed one for the ride north.

Camden Town on Saturday afternoon vibrates with contagious, positive, youthful energy. The streets are filled with colorfully dressed and coifed shoppers looking for the latest bizarre fashion statements, and the air is thick with the smell of grilled sausages and onions. We lucked out, getting a sunny, warm day, which only added to the good vibes on the street (as did another particularly sweet odor).

We hit Vinyl Addiction, off the main road, and scored some great records. I got mint mono original Parlophones of Sgt. Pepper and With the Beatles for $l35 total, and found a few other great discs, including mint stereo copies of Roy Orbison's Greatest Hits, Vols.1 and 2, on Monument (impeccably pressed by British Decca), for $l7 each. I wanted them, but had original American copies; rather than pig out, I did the right thing and generously alerted Lauerman to them. This doesn't happen often where records are concerned—I am a vinyl animal. I'll spare you the $l1 LPs we got next door at Shakedown Records.

We could have spent the rest of the day record-shopping, but we didn't want to keep Roy Gandy waiting at the platform. We regretfully got back on the tube and headed for Waterloo station, where we caught the train to Wickford.

Greeting Gandy

I'd lunched with Roy Gandy at HI-FI '97, and met Roy and his girlfriend Annie for breakfast at HI-FI '98. Gandy was more than pleasant company, giving off the serenely charismatic vibe of a contented, low-stress guy—something I could not relate to at all. He was charming, fascinating, and somewhat mercurial. What I remembered most about our meetings was what a good listener he was—something I'm still learning how to be. I particularly remember his unexpected silences after I'd said something provocative, which, purposeful or not, somehow managed to elicit from me more than I'd planned to say. What came out of my mouth in those instances actually surprised me.

I left both meetings with Gandy strangely energized, feeling that he had a rare ability to draw from me (and, I assumed, from others) more than I thought was there to give on whatever subjects we touched on.

Gandy and Annie met us at the train station. We drove (on narrow, shoulderless, two-lane roads at heartstoppingly high speeds in his "utility" car, a V6 Volkswagen) to a quaint town on the Thames estuary, where we drank beer and ate raw cockles—small, scalloplike creatures that grow in abundance off shore. When the tide is out, as it was then, the boats either rest on double keels or keel over. Strange—as was the taste of the cockles. But at least the mystery of Quite Contrary Mary's cockleshells has finally been solved.

Later, after dinner, we were treated to more beer and live music upstairs at the local pub. The duo—a hot, fiery-haired singer in a skintight dress, and a lanky, dexterous folk/blues guitarist who sat for the entire set and kept time on a suitcase "kickdrum''—put on an amazingly eclectic and energetic show, sounding more like a trio or a quartet. The visit was off to a good start.

Gandy's house in the country is a former rectory on 10 acres that he's turned into a giant bachelor pad (there's a roomful of guitars off the living-room/hi-fi auditioning room). We were shown our rooms—mine came with a hot tub. The rest of the American entourage, 14 in all, arrived the next morning. We spent the day getting acquainted, exploring the house, taking in the local sights—which included a stone church built around 500 $Ba.d.—and eating.

And eating. The country breakfast could have sufficed until dinner, and lunch could have sufficed until the next morning's breakfast. But there was this fabulous wild duck dinner with all the trimmings...Besides, I'd let on that I liked to sing, and Gandy had corralled me into singing "Save the Last Dance for Me" with his group, which was the evening's entertainment. We rehearsed a few times during the day; I ended up doing okay, but the group was quite good. Gandy did a solo turn on a droll, hilarious, bawdy song called "Isabel," about a Monica Lewinsky type who "collects" sexual encounters at famous venues. She's done it seemingly everywhere but the Royal Albert Hall. You can guess how the song climaxes.

In case you're wondering where Gandy fed and entertained the crowd, he's turned a large, quite ancient, wooden-beamed space attached to the main house into a combination dining room/nightclub, complete with a stage outfitted with Rega hi-fi, which works surprisingly well as sound reinforcement gear.

He plays! He sings! He heads a hi-fi company employing more than 40 people! He appreciates fine wine, food, and guitars. He even designed and built his own indoor swimming pool, and cemented in every one of the tens of thousands of tiny tiles himself! He makes his own clothes! (No, he doesn't.)

If the purpose of inviting the dealers across the ocean was to have Gandy charm their pants off, it was an unqualified success. Gandy opened his home to the hordes, and was as gracious and generous, in a totally selfless and unostentatious way, as a host can be. He wasn't trying. He just was.

Rega factory tour

On the second day, after yet another scrumptious breakfast ("Dynamite ham!''—Alvie Singer in Annie Hall), we hopped on a bus and made the rounds, hitting one of Rega's subcontractors and both of its factories. The subcontractor "stuffs" Rega circuit boards with resistors and diodes and the like, and subassembles other board components by hand.

I'd never before seen the automated process, and it was fascinating to watch. It begins with reels of capacitors, resistors, and other small parts. Each spool contains hundreds of one value of component, which are arranged parallel to each other and held in place with a kind of masking tape on either side.

The reels are locked onto hubs. A computer program tells the machinery when to pull what component from which reel in order to assemble a new reel containing multiple components of various values. Once the master reel has been assembled, the boards roll through, stopping long enough to get "stuffed." It takes mere seconds.

Once stuffed, the boards are loaded, up to 12 at a time, onto a metal template. Holes punched in this template correspond to the board layout, so the unsoldered ends of the components protrude from the bottom. The template is then run through a liquid-solder bath. The solder adheres only to the parts protruding through the bottom of the template. I hadn't known how any of that was actually accomplished—I just took it for granted—so seeing the process was really informative. There was also some labor-intensive hand-soldering and trimming.

The finished boards are then packed into defective Rega Planar dustcovers (I kid you not) and shipped to the new standalone Rega facility, which Roy Gandy designed and had built to his specs. If you didn't know it, you'd guess it when you arrived there. The new brick building is trimmed in "Rega green," which is also the color of the address: a big "6."

It sounds corny, but from the outside, "6" looks like a "happy" building. The interior, also trimmed in Rega colors (green, yellow, purple), is a big, open, mostly naturally lit two-story space where Rega loudspeakers and electronics are assembled. It was in "6" that I became fully acquainted with the Rega philosophy. Our guide was Gandy's right-hand man, Phil Freeman—like Gandy, another amiable, low-stress guy. Though Gandy accompanied us, he mostly observed, letting Phil and the workers at each station we visited do the talking.

Rega does not use assembly lines. Rather, one worker builds a product in its entirety. The company is nonhierarchical—while Phil Freeman is essentially in charge of day-to-day operations, no one is "boss" in the usual sense. Which is not to say that chaos reigns at Rega. Quite the opposite—the factory is very well organized, and everyone understands what is expected of him/her.

We visited the various test benches, where circuit boards and CD drives are pretested on ingenious jigs built from rejected Rega turntable plinths. Then we watched a worker build a Rega Planet CD player from subassembled, pretested parts, beginning with the cast aluminum semichassis, which in various guises is common to the entire Rega line of electronics. It took just minutes for the worker, using a few simple tools, to put together a Planet from the 20 or so parts laid out on the bench. Those parts included screws and other common parts, along with Rega's most uncommon, deceptively simple CD-loading system.

It didn't take long before we understood (it was never stated) that everyone takes pride in what they do at Rega. Gandy takes special pride in presiding over a particularly self-sufficient company that wastes neither time nor resources. Rega designs and builds many of its own machine tools and manufacturing devices.

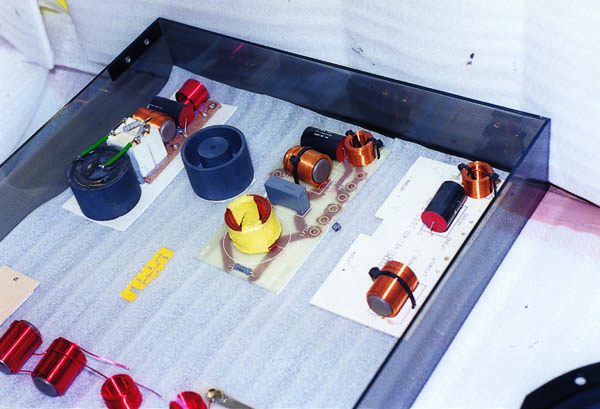

"Simplify" is a key word at Rega. For instance, a new loudspeaker, the Mira, uses a Rega-designed and -built 7" bass driver. We were shown the prototype eight-element crossover and a somewhat more elegant six-element production version. Before production commenced, however, it was discovered that a large inductor and a few other components could be eliminated if the new driver's voice-coil could be wound with eight layers. But how to manufacture such a voice-coil? Apparently, it hadn't been done before. Rega's machine-shop and tooling genius, Ken Palmer, built the precision winding device; we watched it coil row after perfect row of thin copper wire under the expert guidance of a Rega worker. The final production crossover uses three components.

We watched various loudspeakers in the Rega line being assembled, and, in a separate room, Rega's full line of electronics—CD players, tuners, integrated and separate pre- and power amplifiers—being burned-in and finally listened to, one piece at a time. Everyone was impressed with both the ingenuity and simplicity of the designs, and the high quality of the parts and overall construction—especially when you consider the reasonable prices Rega charges for its products.

Not a revolving turntable in sight

We visited the turntable- and tonearm-manufacturing part of the operation last—partly because it's located in another facility some distance away (the tour could have ended in the new factory), and partly, I'm sure, because while most American audio consumers and dealers are quite familiar with Rega's analog achievements, the rest of the line is less well known.

As we boarded the bus headed for Rega's original facility, I realized why it's well worth the company's while to invite dealers to see how its products are made. Without regard to the business side—terms, margins, all that mind-numbing stuff—I could see there wasn't a dealer among the assembled who wasn't impressed by what they'd just seen and heard. No one asked the workers about their salaries or bennies, but clearly, this was no Nike factory! Rega employees seem genuinely proud of what they do and what they build. And the working conditions are more than pleasant. No PC at Rega! A few walls are adorned with photos of naked women (and, at a few of the women's stations, naked men), and no one seemed "offended" or embarrassed—not even Ken McStarr, the Irish janitor.

We entered a much smaller, more cramped building, headed up a narrow flight of stairs, and found ourselves in a reception area where Rega turntables hung on the old brick wall above a giant nonturning table's worth of food. After lunch we got to the heart of the matter: Rega's r&d and design shop, and the turntable- and arm-manufacturing facility.

We were rejoined by machining guru Ken Palmer, who showed us his design facility and some machine tools, including a mold that produces the tiny rubber dampers used in Rega's cartridge line. We saw "raw" turntable parts, and an arm fresh from central casting. We also learned a bit of Rega history during this part of the tour.

Rega's first analog product was a turntable—the Planet—that was mated with a Japanese arm, the Lustre. When Roy Gandy decided to produce his own tonearm in the early '80s (he's a formally trained mechanical engineer), he insisted on structural rigidity above all else. The only way to achieve it, he figured, was a one-piece casting of aluminum that included the headshell. But a casting mold is prohibitively expensive. Gandy went ahead and spent the money anyway—some $l80,000. That's a lot of money today and was even more then, but Gandy wanted to do it right.

The result is the classic, elegant Rega arm analog fans around the world know, love, and own—over 250,000 of them. That giant leap of faith made in the shadow of the Compact Disc, which Gandy knew was coming, was the best investment he could have made. No one today can afford to spend that kind of money on a casting—the numbers won't justify it—and it has given Rega a tremendous advantage in analog. That's one reason the arm is ubiquitous.

From Palmer's shop we went to the turntable assembly area, where we watched a Planar 3 being put together. It didn't take long to build the simple, high-performance 'table: Screw on some feet, thread the mains cord, drop a bearing assembly into the hole, top with the spindle/subplatter assembly, pop in the motor and its suspension, bolt on the arm, and it's basically complete. So simple. Why didn't anyone else think of it?

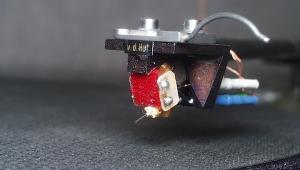

Next, we visited the cartridge-manufacturing area (there are four models in the line). An exploded comparison of Rega's design with that of another British manufacturer hung on the wall—I don't have to tell you which uses fewer parts. Rega winds its own coils in-house on machines it designed and built. They wind two coils on one oddly shaped spindle, and place this assembly in yet another device conceived and built in-house, which precisely folds the spindle in half, resulting in two parallel coils. In yet another jig, a second assembly folded the same way is inserted into the first at precise right angles. Then they're soldered, forming the four coils needed to generate a stereo signal. Rega's scheme does it with half the parts used in most other designs.

The coil assembly is then secured to the cartridge body, a damper is pushed into a hole in the body, and the cantilever/stylus/magnet assembly (sourced from Ogura, Japan) is inserted through the damper. The cartridge is fitted into a jig, and azimuth is adjusted using a high-powered microscope. Output and channel balance are then measured, and, depending on the cartridge model, output and channel balance are adjusted by repositioning the cantilever/magnet assembly and its proximity to the coils.

The top-of-the-line Exact ($595) uses the highest-quality diamond tip/cantilever assembly, and is adjusted to the most exacting (ahem) mechanical and electrical standards. The only downside to this simple, effective, totally handmade design is that the stylus is not user-replaceable.

I was most interested in watching how Rega arms are assembled; there's some controversy over whether the Rega RB300s used on Rega 'tables are identical to OEM (original equipment manufacturer) arms that other manufacturers buy to put on their own turntables. A few years ago, a mail-order specialist was selling an OEM Rega arm it claimed was "identical" to the RB300. Apparently there was a legal battle and the claim was removed. Merit or politics? Inquiring minds wanted to know.

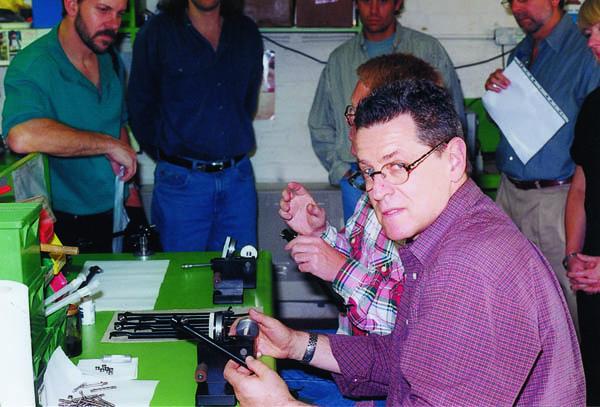

Not only did I get to watch an arm being assembled, I got to build the critical part of it myself. (You'd better hope you don't end up with it.) The key to the Rega arm, aside from the casting itself, are the preloaded bearing assemblies. Rega sources the ball races, made to Rega's spec, from the largest manufacturer of them in the world; the spindles are also custom-made.

First, the bearing housing is press-fitted into the arm. Then the fun begins: One of the specially trained bearing assemblers picks a spindle and begins fitting bearings onto it. There are variations within the allowed tolerances for both bearings and spindles, and the assembler must find bearings that fit tightly on the spindle. This can take up to 20 minutes. The assembly is pressed into the arm-bearing housing, and then a nut is applied to the end of the spindle. The assembly is fitted into a special jig, and the nut is tightened according to both a dial gauge and "feel." This is where skill and experience come in. Properly done, the locking-down process "pre-loads" the balls in the bearing race. This is done for both the vertical and horizontal bearing set.

Apparently, OEM arms aren't as tightly spec'd, thus less time is spent mating bearing races and spindles. Does this really affect sound quality? I can't answer that, but clearly, that's the only difference between the RB300 and the OEM version. Having assembled an arm made me understand why Rega insists that disassembling the arm (to modify it or change internal wiring) by unscrewing the bearing pre-load nuts is nuts! My advice? Don't do it—unless you know exactly what you're doing.

Rega insists that, while the cable used on the RB250 and 300 arms looks "cheap," it is actually a very good, low-capacitance cable, and that changing it will do more harm than good to the arm's sonic and mechanical performance.

The more expensive RB900 arm (a steal at $995) uses the same casting, finished differently and fitted with higher-tolerance, higher-cost navigational gyroscope bearings assembled only by chief arm builder Angie Rosewarne. The 900 also uses a tungsten counterweight, a higher-quality Klotz wire, and Neutrik RCA plugs.

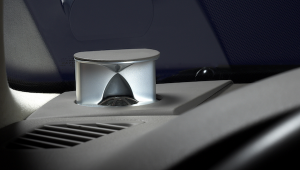

We ended our daylong tour in chief electronics designer Terry Bateman's lab. We were shown a new two-box CD transport/DAC, and some dramatic visuals for future Rega products. Also on display was a prototype for a brand-new Rega turntable, the Planar 25, so designated because this year marks the company's 25th year. The 'table will retail for $1275 and features a new $695 arm, the RB600 (actually a variation of the arm), finished in a striking natural aluminum and including the same high-quality cabling as the RB900. The Planar 25 will probably feature a wooden-framed plinth identical to that of the 9, plus a hard-mounted motor like the 9's (for better speed stability), made possible because Bateman has come up with a simplified version of the 9's outboard motor drive that cancels most of the motor's vibration.

Finally

Back at Gandy's, we spent the next half-day listening to the new speaker and comparing the Planar 3 with the prototype Planar 25. If the final version is as good as what I heard, there will be many, many used Planar 3s on the market as owners trade up to the richer, more detailed-sounding 25. I've been promised the first production unit off the assembly bench; if I move fast enough, Stereophile will have the first review published anywhere in the world, along with an interview I conducted with Gandy during a rare private moment.

Then there was the afternoon of archery and four-wheel motorbiking, which made the trip feel like summer camp. The ensuing dinner of roast pig has already assured me an afterlife in Hell, and—

I know what you're thinking: I went on a junket, got sucked in, and lost all objectivity. Not so. Of course, everything at Rega cannot possibly live up to the idealized, sanitized version we were shown. Some days must be accompanied by screw-ups, recriminations, yelling, screaming, the pulling-out of hair. That's real life. But given what I've seen and heard in the well-made, ingeniously designed, bargain-priced Rega products I've reviewed and had a chance to informally audition, and what I learned about Roy Gandy during our Stateside breakfasts, what I observed during my visit to Rega was not at all surprising. I admit it: I'm a fan.

- Log in or register to post comments

That was a fun blast from the past — and a welcome reminder how both MF and Rega kept the analog flag flying during the darkest days of the vinyl eclipse.

It also made me hug my beloved '90's-vintage Planar 3 and little tighter to my breast, hearing where it came from and the care taken in building the RB300 and the TT itself, and seeing what a cool guy Roy Gandy was. Makes me want to get in the Hot Tub Time Machine and go back to sniff the 1999 air in Camden Town....

I hope you put on the stylus guard first! Of course Roy still is a pretty cool cat but he's got to get hip to record cleaning!

Great reread mikey.

This just confirms that Roy Gandy is every bit of what we have heard over the years, a man who thoroughly commands and enjoys a (rightfully earned) most envious of existences, geez. Good that you were invited to share in it and the Rega product insight and share it with us.

Just an observation, it appears as if Rega and Linn, as creator/manufacturers of their own products, from the smallest of details, is more similar than different with everything I've now seen. I enjoy and admire both for their intelligent product designs and sound.

In your last comment, don't tell us that Roy comes from the same nasty little European habit previously touted publically by Ivor Tiefenbrun, that of just letting the stylus "clean" the record grooves while playing! Damn primitive. Maybe the unwashed masses (of UK vinyl) could benefit from the virtuous practices employed daily by us gentle folk here in the colonies.

Happy Listening! ;^)>

Yes, Roy is/was in that school. Once I visited him after getting a big haul at the late, lamented Beanos in Croyden. I said "Let's test the 'the stylus will do the cleaning' theory" on some of these used records I bought."

So we did. Midway through the first fairly dusty, static-y record, the combination of the ball of fuzz and the static charge actually lifted the arm from the record and it hung in mid-air!

Since I was a guest, I simply said "No comment!"

Mikey- You need to bring back your Ronald Reagan Jet Black Grecian Formula hair!

I looked at that pic and had to ask myself, how much more black could it be ... and the answer is none. None more black!