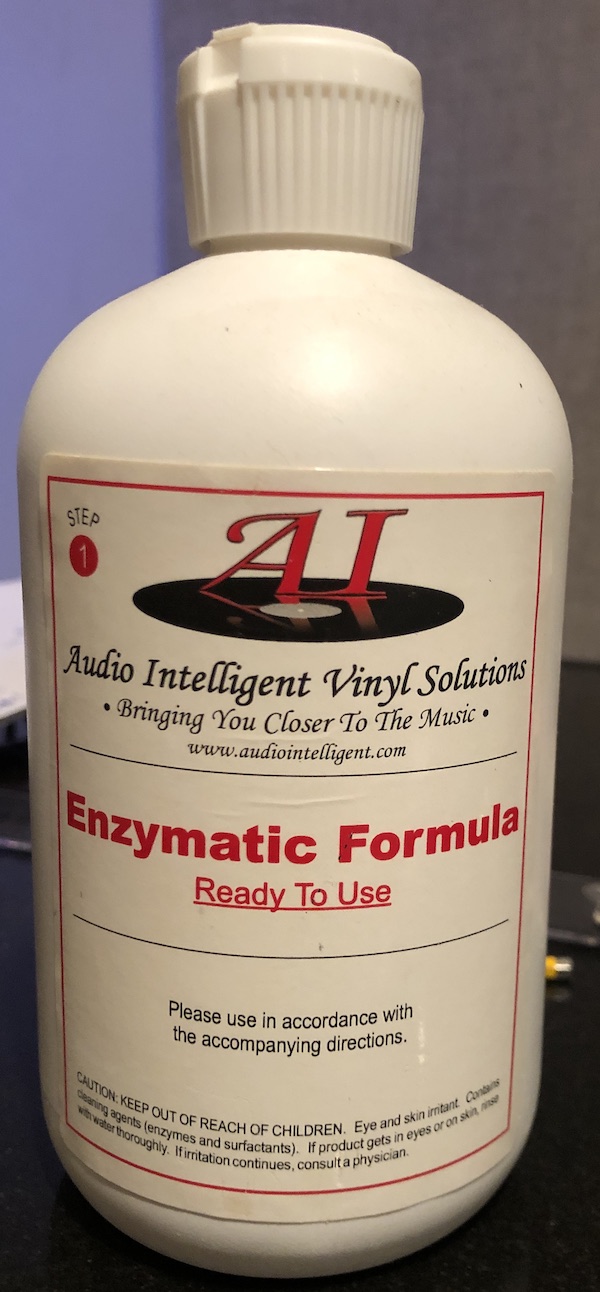

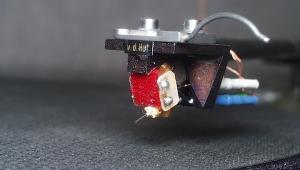

I would have to check, but I think the last time I bought some AI #15 a couple of years ago it was upwards of $45 a quart :)

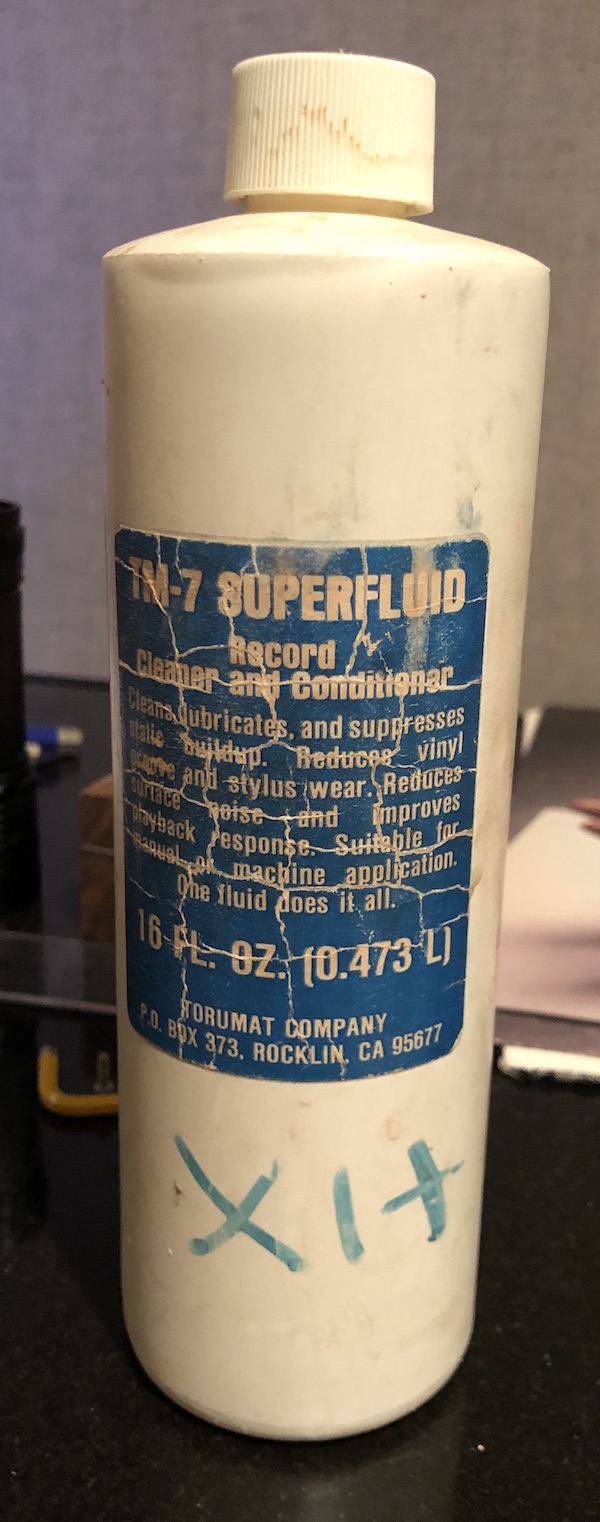

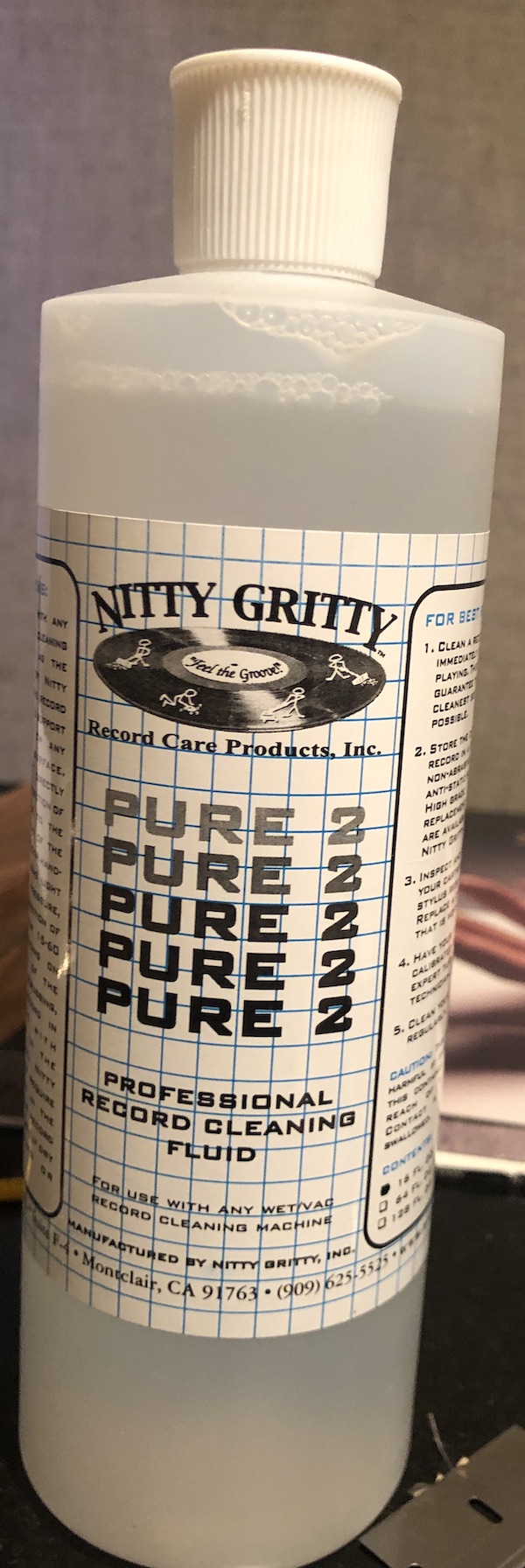

My friend and I had an 'old' gallon bottle of TM7 for years and years which we swore by using his Nitty Gritty. Somehow the bottle got a hole in it (with probably half of it left!) and we found it empty one day. We panicked, 'WHAT ARE WE GONNA DO NOW?!!!' Fortunately (and thankfully) since then I discovered AI fluids. Also now, FWIW I'm TRYING to construct my own US cleaner (getting those revolutions down have been a challenge!)