Analog Corner #106

"Do you want to see how they build Pro-Ject turntables?" It was Sumiko's John Hunter, phoning me out of the blue.

"Sure!" I've reviewed a few Pro-Ject designs over the years, along with the Music Hall 'tables, which are built in the same factory, and I've long wondered how one small company in the Czech Republic can manufacture such a wide array of products while making almost every part in-house. When Hunter added that the visit to Pro-Ject would be bracketed by stops at Vicenza, Italy and Vienna, Austria to visit (respectively) Sonus Faber and Vienna Acoustics, I was ready to pack. Besides, between the lunacy of January's Consumer Electronics Show and the assembly line of products arriving at and departing from my listening room, I needed a break, hectic though the five-day trip would be.

I took a Saturday-evening flight out of Newark's Liberty International airport, and, after a short stopover in the Netherlands, arrived at the fogbound Venice airport on Sunday afternoon. There, a car waited to take me to the picturesque Michelangelo hotel, nestled in the hills surrounding Vicenza. Unpacking my valise, I was thrilled to find a note from the Transportation Security Administration telling me that, in addition to being X-rayed—which I'm all for—my bag had been rifled through at Liberty International in a hunt for "prohibited items."

Like what? Weapons of mass destruction an X-ray machine might miss? Calico cats? Gay marriage licenses? If they have the "courtesy" to tell you they've pawed through your stuff, don't you think they should at least be considerate enough to tell you what "prohibited items" they're looking for? Then again, maybe dropping the Fourth Amendment from the Constitution is the cost of securing our freedom.

John Hunter and I were met at the hotel that evening and taken out to dinner by Sonus's Cesare Bevilacqua—a warm, dashing character who takes care of business at the company and is founder-designer Franco Serblin's son-in-law. The simplest of meals is memorable in Italy; I can still taste the delicate, citrusy marinated prawns—as well as the rest of the meal, but I'll spare you.

Next day we visited the new Sonus Faber factory, a gracious edifice of glass and metal end-capped by large, curving structures that resemble cross-sections of airplane wings. The architecture delivers the visual drama a Sonus Faber devotee would expect from the building in which his speakers are made.

The building's interior is even more impressive—bright afternoon sunlight flooded a display of landmark Sonus products downstairs, and there was diffuse, natural light sufficiently bright for manufacturing upstairs. As you might expect, the building's woodwork was exquisite, including dramatic floors and staircases of polished, narrow-strip hardwood.

Serblin took me into his listening room to hear the new Stradivari loudspeaker ($40,000/pair), his final statement in the Homage series. I spent about an hour and a half listening while he and Hunter hashed out some new product plans I thought it inappropriate for me to overhear. Driven by a compact, 70Wpc David Berning ZH-270 tube amplifier (no output transformers, but not OTL), the Stradivari sounded delicate and detailed yet rich and tactile. I'm rarely drawn into lengthy stretches of serious listening in such circumstances, but this was one of those rare times when the music, and especially the sound, overcame the considerable distractions. I found myself inhabiting the mental "sweet spot" where time stands still and even the most difficult, unfamiliar music becomes immediately accessible.

After an unforgettable evening wandering around Venice—punctuated by dinner at Harry's Bar (followed by a good night's sleep)—it was off to Vienna, where we were met at the airport by Pro-Ject president Heinz Lichtenegger—the high-strung dynamo of a Vienna-based audio distributor with a passion for analog and a name that's the opposite of Arnold's.

At the end of the 1980s, with analog on the wane, Lichtenegger began looking around for an inexpensive, well-made, good-sounding turntable that he could offer customers to keep them playing LPs in the age of CDs. By then, both Dual and Thorens were out of the low end of the market, except for really cheap 'tables made of plastic.

At the suggestion of some friends he was visiting in the newly formed Czech Republic, Lichtenegger paid a visit to a factory that specialized in building turntables—probably for most of the Iron Curtain countries, who were late to the digital table. But being first isn't always best.

Most of what Lichtenegger found in the old-fashioned facility were bad copies of semi-automatic designs that had been popular in the West a decade earlier. However (the story goes), in a dark corner of the factory he found a simple little turntable—belt-driven, with a heavy platter—that looked as if it could. When he expressed interest in the ugly ducking, the factory managers, fresh from half a century of oppression, were incredulous.

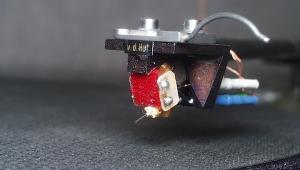

Lichtenegger took the 'table home and, pleasantly surprised by its sound, began looking for ways to improve it. He proposed sapphire cones and hardened steel points for the arm bearing, a one-piece tonearm-headshell design in place of an attached one made of plastic, bronze bearing bushings and a Teflon thrust pad instead of a cheap ball, a precision-machined flat belt instead of a "rubber band," an MDF plinth, a felt mat, a more accurately machined and balanced platter, and copper armtube wiring.

Thus was born the Pro-Ject 1. Built in a separate part of the factory by specially trained workers, the new, low-cost 'table's quality of fit'n'finish and surprisingly high sonic performance caught the eyes and ears of Europe's hi-fi press. Good reviews led to strong sales throughout Europe, including in the UK, which, then as now, wasn't hurting for competitively priced turntables.

Encouraged by that reception, the industrious Austrian expanded the Pro-Ject line of 'tables while improving and upgrading the various components used in their manufacture. Among the innovations were carbon-fiber tonearms and a unique aluminum-alloy platter topped with a layer of baked-on vinyl made from recycled LPs. Pro-Ject also manufactures phono preamps and electronic speed controls, which are available as outboard products or built into certain turntable models. Tonearms of aluminum (9") and carbon fiber (9", 12") are available separately, as are glass platters.

Pro-Ject's turntable line is varied and extensive. There's the Debut, the 1 Xpression, the 1.2, the 1.2 Comfort, the 2.9 Wood, the 2.9 Classic, the 6.9, the Perspective (the one I really like), and the RM 4, RM 6 SB, and RM 9. (The RM series is called "RPM" overseas. In deference to Immedia's RPM line, Sumiko uses "RM" in the US.) Add some special models tailored for specific markets, and the 'tables built to Music Hall's specs for sale exclusively in the US, and Pro-Ject makes an impressive array of products in one factory in rural Litovel. One could argue that the Pro-Ject line—flat belt and crowned aluminum pulley here, O-ring acrylic grooved platter there, MDF here, acrylic there—lacks consistency. One did.

But first, some wine...

We drove from the Vienna airport north through the Austrian wine country, on our way to a hotel where we spent the night before driving the last three hours to Litovel. Lichtenegger had made arrangements for us to enjoy a wine-tasting at the Taubenschuss winery in Poysdorf, where we drank more than we tasted, and ate more local cheeses and hams than we should have—but the difference between what we were served at Taubenschuss and what's available at the local deli is roughly equivalent to the difference between a burger at Mikey D.'s and one at New York's 21 Club. We ate while the eating was good, and it was good. When it comes to vino, I'm no Bob Reina, but I found the white wines suitably complex and finely finished. When at last I was finished, I was pleasingly plastered and ready for nappy-nap.

Visiting Pro-Ject

Next morning we set off for isolated Litovel, which was as drab as you might picture it under a winter sky, though I was told it's now far more colorful and cheery than it was a decade ago. The original factory, a short distance down the road from the new, was described to me as a forbidding, Soviet-style 1920s affair, painted dull municipal green inside, complete with enormous portraits of Lenin and, I think, Stalin—left hanging, I guess, as a reminder of what used to be.

The new factory is a modern, seven-story building dedicated to building turntables—an incredible 50,000 last year—using a mix of modern CNC machine tools from Japan and Korea, and vintage but still serviceable gear dating back to the Soviet era. The tour began in a contemporarily furnished meeting room where we met the plant's manager, Jiri Kroutil, and Jiri Mencl, a burly factory veteran from the communist days, who implements the designs and oversees the manufacturing process.

Walking past stacks of boxed turntables, we entered a well-lit factory space containing, in various states of assembly, more turntables than I've ever seen in one place. Everything at Pro-Ject is hand-assembled, and virtually every part of a Pro-Ject 'table that you can see—tonearms, platters, most plinths, dustcovers, arm rests, tonearm cables, drive motors—is made in-house. The exception is the arm ball bearing, which comes from Switzerland.

What impressed me most about the operation was that even the least expensive model, the Debut Mk.2 (ca $299), got a full regimen of inspection and performance testing. Allowing unit-to-unit variability is one area where money can be saved when manufacturing budget gear. Conversely, when you buy premium-priced stuff, one thing you're paying for is consistency. But any Pro-Ject you buy, from the least to the most expensive, receives the same degree of attention, and isn't boxed until it has met its published specifications. That's an admirable achievement, given the prices and the sheer volume of 'tables produced at Litovel.

The Debut, available in a variety of "now" colors, piqued my curiosity. This plug-and-play model comes complete with Ortofon OM 5E moving-magnet cartridge, and while it uses a stamped steel platter and so can't be used with a moving-coil cartridge, I'm curious to hear it—first, right out of the box, and then with, say, a Shure V-15VxMR (which costs as much as the 'table and supplied cartridge combined). Despite its price, the Debut's drive system includes an AC synchronous motor of which Pro-Ject is very proud, a crowned dual pulley of aluminum, and a flat, precision-ground drive belt. The Debut is also available with a built-in phono preamp and pushbutton electronic speed control.

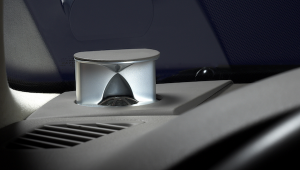

During the tour, I was given a defense of the integral pressed headshell, of which I'd been somewhat skeptical in reviews. It just seems too thin to not resonate at a nasty frequency when excited, but I was told that Pro-Ject feels that the rigidity of the integral headshell trumps its lightness in terms of energy transfer. For now, the carbon-fiber armtubes require separate headshells, but I was told that soon there would be a one-piece carbon-fiber armtube with integral headshell—probably something similar to what Wilson-Benesch does. The folks at Pro-Ject also made special mention of the AC synchronous motor they build. They think it's better than any motor found in some other turntables priced well above Pro-Ject's comparable models.

I watched one poor woman who sat at a jig, bending and shaping those bent, looped rods that hold the monofilament for the antiskate weight on Pro-Ject turntables one at a time. Not that she considered herself poor—after all, she's got a genuine manufacturing job of the sort we used to have here in the US. I watched another woman inserting pivot pin after pivot pin into the Debut's armrest assembly. Another inserted wiring harness after wiring harness through hollow armtubes.

When you look at a finished turntable, it's difficult to appreciate the amount of labor that goes into its assembly. Watching the pieces being subassembled and then, finally, assembled into a final product drove home both how much work there is in putting a 'table together, and just how many parts a single turntable contains. How any of these turntables can be manufactured, boxed, shipped, exported, distributed, and then sold at retail for as little as they sell for—especially the Debut—is difficult to fathom.

At one point during the visit, I was shown a new limited-edition, gold-plated Pro-Ject Phono Box preamplifier. "It's to celebrate the sale of our 100,000th Phono Box," Lichtenegger announced proudly. There's no arguing with that kind of success.

I came away from my afternoon at the Pro-Ject factory mightily impressed by what I'd seen. Everyone I met there, and everyone I watched at work, was clearly dedicated to producing quality products. And the decision-makers were just as clearly dedicated to making continual upgrades to every facet of manufacturing and production.

Not that there aren't a few unusual quirks at Pro-Ject. Despite all of the company's manufacturing expertise, getting them to put the decimal point on the counterweight scale seems all but impossible. Now, and as far back as I can remember, if you buy a Pro-Ject 'table, its scale will read "10," "15," and "20" when it should read "1.0," "1.5," "2.0," etc. When I brought that up at Litovel, people there got a faraway look in their eyes, as if I was asking the impossible from a factory that seems to do just that every day. Oh, well.

Back to Vienna

The long ride back to Vienna consumed the rest of the day. We arrived at night at a glittering, modern city reminiscent of Boston but that seemed to peel back time the closer we got to its core. By the time we reached the Ringstrasse district, we were in Mozart's Vienna. We pulled into the Palais Schwarzenberg hotel, once home to Prince Charles Schwarzenberg, who whupped Napoleon. I guess he deserved to live in style. For two evenings, I did too.

Next day we visited Vienna Acoustics, where I met designer Peter Gansterer and his significant other, company president Renate Köbert, and Gansterer's sister, Maria. We sat around a table in their office laughing for an hour (something about blood spurting from my wrist from a coatimundi bite—don't ask), had lunch (Wiener Schnitzel), and then I left to visit Christian Bierbaumer's Blue Danube Records in Tullne, about 45 minutes outside of Vienna. I've yet to hear a Vienna Acoustics loudspeaker, but they certainly look serious. Having met their designer, I get the feeling—just a feeling—that they'll sound at least as good as they look (footnote 1).

Blue Danube was something of a disappointment. Lots of records, and many fine ones, especially classical—but not what I'd call a premium collection overall. The rock selection was decent, but there was nothing of note in the jazz section. Nor was it the classical watering hole that the UK's Gramex was in its heyday. Still, I came away with a few good LPs, including an early-'70s UK EMI boxed set of Klemperer's cycle of Beethoven's symphonies. I also got a chance to inspect Blue Danube's extremely well-built vacuum record-cleaning machine. It's come a long way from the one I wrote about and pictured, after having spied it at the Frankfurt Hi-End Audio Show a few years ago. Someone should import this quiet, versatile, ultra-compact unit. Then another heavy meal, a good night's sleep, and back to America.

Here's what I learned from my trip

The Sonus Faber Stradivari Homage is among the most seductive-sounding loudspeakers I've ever heard. The Pro-Ject factory turns out products of even higher quality than I'd originally suspected, and we can expect even better turntables from them in the future. The folks behind Vienna Acoustics are awfully nice; I'd like to review some of their speakers. I watched an importer at work, consulting with companies whose products he sells, trying to make sure they understand his customers' needs. I've read the bellyaching online about "middleman" importers who simply add a link of price increases to the distribution chain—but the bellyachers are the same folks who buy gray-market goods and then, when something goes wrong, contact the American importer for service.

It was clear from watching John Hunter and Heinz Lichtenegger at work—and seeing the amount of inventory Lichtenegger buys and stocks in his warehouse, and knowing what Sumiko's inventory is like—that overseas manufacturers take into account distributor feedback when they develop new products, and that importer-distributors play an important role in the production-distribution feedback loop critical to the industry's continued health and growth worldwide. Complaining about the added cost of this link is like complaining about the considerable amount you pay for the fortified boxes in which your favorite components are shipped. It would be nice if you didn't have to pay for the box, but how else can the product be safely shipped from the factory to your home?

All the Nonsense that's Fit to Print

My ongoing war with the Circuits section of the New York Times continues. They keep publishing "advice" on how to transfer LPs to CDs while neglecting to tell readers to clean the records first. I continue to send them e-mails about it. Recently, when they published a stupid story on the subject, I sent the Circuits editor the following (condensed to make room). I hope you enjoy it.

"Dear Circuits Editor:

"Flash!!! Want to see more clearly through your eyeglasses? A new computer program and an optical sensor that goes over your glasses can actually filter out the dirt and grime that coats the lenses over time! It costs about 300 dollars and requires you to locate the dirt on a digital rendering of the lens appearing on your computer screen and then go over each fleck with your mouse to erase them. It takes about a half hour to 'clean' both lenses digitally. And then, the dirt will seem to be gone! It's a digital miracle!

"You may ask, 'Why not clean the glasses with a lint-free cloth and some lens cleaner? Takes a few seconds, costs a few cents.' But obviously you wouldn't ask that question, since no one at Circuits writing about transferring LPs to CDs ever mentions cleaning the record before doing the transfer!!!!!!

"Just two weeks ago, I sent this to your Q&A guy:

"'Dear Mr. Biersdorfer:

"'I believe we've had this discussion before, but here it is again. The best way to eliminate "hissing and popping" from vinyl when transferring to CD is to clean the record first instead of running it through some music-destroying filter. Filters and crackle-and-pop programs should be used only as a last resort. The best advice to give someone about transferring vinyl is to start with clean records, and be sure your turntable is properly set up and has a good and clean stylus. Without that, it's a worthless endeavor.

"'I realize this procedure is in the dreaded analog domain, but it is worth mentioning anyway. I can send you hours' or days' worth of LP-to-CD transfers that were done without any filters or crackle-removing computer programs, and you will hear nary a pop or a click or a hiss or anything other than "perfect sound forever" because the records were played back properly....I would be happy to transfer any LP of your choice for you using a clean record with no filters or computer programs to demonstrate this to you.

"'Happy holidays,

"'Michael Fremer

"'senior contributing editor, Stereophile

"'PS: If you'd like some info on cleaning records and playing them back properly, I'd be happy to supply it for the benefit of your readers.'"

"Did I get a response? No!...I have beat you guys over the head with this for the past few years every time there's a story like this, or a question answered about transferring vinyl to CD, but for some reason you're not interested in giving your readers the correct information, which is: Before you begin transferring your records, you should (all together, digital geeks!) clean them.

"Then, unless they're trashed, you won't need to dick around with music-destroying filtering programs. Clean records won't have 'crackles and hisses,' and writer Roy Furchgott's contention that 'crackles and noise' are what gives analog its 'warmth' is stupid.

"No one who prefers listening to vinyl...likes listening to pops and clicks and noise any more than people who prefer eating fresh food to frozen think rot and mold are what gives fresh food its good taste, but guess what? If you...clean the records before playing you usually won't hear pops, crackles, and 'hisses.'

"I know, I'm just an angry adolescent pest weirdo writer. But when you're nice and get ignored and you keep offering good, useful information and you continually are ignored, and you keep reading the same wrong bullshit in the New York Times, and you actually care that the readers get good, useful information, which is something you guys clearly do not, guess what? You get angry and you begin writing in caps...."

Michael Fremer

senior contributing editor, Stereophile

writer, "Analog Corner" column

Footnote 1: Robert Deutsch favorably reviewed Vienna Acoustics' floorstanding Mahler loudspeaker in April 2000 and the company's smaller Mozart in January 1997.—Ed.