Analog Corner #11

(Originally published in Stereophile, June 12th, 1996)

I'm always surprised when I read a letter saying that this column helped convince a reader to invest in a good turntable and start enjoying analog. I shouldn't be, but I am. And I'm also amazed by how many such letters I see published, or receive via fax from the home office in Santa Fe, or by e-mail on CompuServe (Footnote 1). Ditto when I run into people at record and hi-fi stores who tell me the same thing.

I even meet newly converted analog devotees at the Toshiba-sponsored Home Theater seminars I've been participating in over the past year and a half. Although my name isn't used to promote these events, inevitably one or two Stereophile and/or Stereophile Guide to Home Theater readers are in attendance, and after the three-hour presentation (it is comprehensive) they come up and tell me how much they appreciate the fact that I've pushed them over the top and into the groove. That's about as good as it gets for a writer/advocate. It's clear proof that the old and new technologies can happily coexist.

I'm not surprised that no one has ever complained about taking the analog plunge. Not once! How could I be surprised? I sit here every day listening, and while digital has gotten surprisingly good lately, the fundamental sonic, emotional, and physical differences I hear and feel between the analog and digital musical experiences remain unchanged. That's why even those who have invested in modestly priced turntables end up expressing the perceived differences in the same terms used by those lucky enough to own high-priced spreads.

Although analog may be warm-sounding, it is not "warm and fuzzy," as one letter writer who obviously hasn't taken the plunge claimed recently. If your analog system sounds "fuzzy," it needs some work, or your records need cleaning. Clarity and focus are two areas where properly set-up analog consistently outperforms digital.

And once again, since I have the bully pulpit, I must take exception to engineer Gabe Wiener's comments about digital's "accuracy" versus analog's ("Letters," November '95, pp.0–1). As reported in May's "Industry Update," I visited Sony Studios recently and heard a live mike feed versus a 0-bit PCM conversion, never mind 16-bit. I'm here to tell you that 0-bit digital doesn't sound like a live mike feed. Would an analog recording sound like the mike feed? No, but no one's making such grandiose claims as "accuracy," "perfection," and "transparency" for it.

The problem for me is that what's wrong with digital (particularly with what happens between the A/D conversion in the mastering suite and the delivery of the bitstream from the CD to the D/A converter in your processor) is more irritating to the ears, and more damaging to the music, than what's wrong with analog—though the gap is closing in many important ways.

Conventional wisdom has it that you can get much higher performance from inexpensive digital than from budget analog, but I'm starting to think otherwise. With a little care in initial set-up, some tweaking, and careful record cleaning, even a very inexpensive analog front-end can display the superior qualities of the medium without letting its deficiencies get in the way of musical satisfaction.

Home remedies

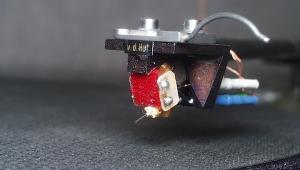

Back in the late '70s, when I was living in Los Angeles, you hardly ever saw a turntable without a pile of gummy Star Type Cleaner glopped onto the arm's headshell, and pressed between the headshell and arm, and between the arm and pivot assembly. I'm not sure who started this funky-looking damping tweak—it could have been John Dudley at Absolute Audio but I don't remember. I do remember it was at Dudley's that I heard a Koetsu Rosewood for the first time. The Koetsu—an $800 cartridge, in 1979 or 1980 dollars—was a pleasant shock to the auditory system, though I couldn't afford one.

Today, if you own a Graham or a Wheaton or an Eminent Technology ET—or any other high-priced arm without a removable headshell—you probably don't need Star Type Cleaner anywhere. But if you're an analog geek on a tight budget, and you're living with an old Technics, or a Dual, or any other budget or "vintage" 'table, you might give the stuff a try—if you can still get it. There must be a few typewriter diehards remaining. We analog lovers know how that is, don't we? It's one thing to mount a campaign to "bring back the Orbitrac" (we're making progress on that front), but a "bring back Star Type Cleaner" crusade? Count me out!

I checked with my local office-supply store and when I mentioned the stuff (made by Eberhard Faber) the owner laughed. But there on the shelf were a few plastic boxes of it priced at $1.9 and dated "January 1990." So if you look, you can probably find some, though audiophile office-supply store owners will probably up the price to $9.95 after reading this column.

Star Type Cleaner, by the way, is (was?) a wad of purple gumlike stuff that you'd press onto the face of the type to clean off dirt and ink. What's great about it is its weight and consistency: light, and neither oily nor sticky. For audio use you can apply it and remove it without leaving a gooey residue. It's pliable and has excellent damping properties.

To use it, you pinch off a piece and place it between your cheek and gums—oops, wrong product! You knead it until it has softened slightly, then you press it thin and apply it to the top of the headshell, covering the entire surface to a thickness of about 1/8" to 1/4".

If you don't end up with enough, pull the glob off, add some more, and start over. Don't worry if it hangs over the sides or front: You can trim it easily with a single-edged razor blade to make a neat, though lumpy-looking, surface. It's a good idea to clean the headshell face with isopropyl alcohol before you attempt the application. It's also advisable to support the front of the headshell as you press the stuff down—better yet, do it with the headshell removed.

In addition to treating the headshell/arm joint and the place where the armtube enters the pivot housing, obsessives also put tiny pieces over the headshell-wire/cartridge-pin connection. If you try any and/or all of these tweaks, don't forget to readjust your tracking force before playing a record.

Back in the late '70s, I purpled my Lustre GST-1 arm and heard a nice improvement. The Lustre was mounted on an oddball Rotel turntable that used a large, high-torque, Denon direct-drive AC synchronous motor fixed to a simple wooden chassis. (I'll bet someone in Los Angeles is still using that set-up!)

An additional modification I made to that record player was to fill the circular channel on the bottom of the platter with Mortite, another puttylike material that comes in ropelike ribbon coils with paper between the layers, like Dorman's cheese. The Mortite damped the platter and added mass, both good, but because it was difficult to apply evenly all around, it also unbalanced the platter—not good. Still, I felt the Mortite treatment overall resulted in a net sonic gain. I'd proceed with extreme caution with Mortite, but if the platter on your budget turntable is light and "rings," and the motor is heavy duty, it's worth considering. As is damping the whole damn chassis with Mortite—especially if it's plastic.

Store-bought remedies

I've watched mat wisdom shift 180º over the past decade and a half: Soft mats such as Sorbothane were "in" for a time because they "damped" and cushioned the record, then hard acrylic became the standard because it was "impedance matched" to the vinyl for better energy evacuation. Although plopping a record down on a hard surface seems like a bad idea, in reality the grooves are never in any danger as long as you don't spin the record on the platter.

Today, the hard road is favored by most manufacturers (VPI, Basis, SOTA, Immedia, etc.), who use acrylic or other hard-surfaced platters that require no mat. Linn, Rega and some of the other British manufacturers still prefer thin felt. For its vacuum hold-down platters, Rockport uses a really neat (and of course expensive) semihard pebbly surface to protect the grooves from vacuum-induced dirt suck, while SOTA opts for an ultra-thin cloth covering on its vacuum platters.

If you've spent a bundle on one of these well-engineered products, the smartest thing you can do is not to second-guess its designer. Use the mat or surface the 'table comes with. However, if you're making do on a budget, or if you decide you do want to second-guess the designer, experiment away! That's one of the advantages of being analog.

I'm not a big fan of felt mats. They attract dust, which ends up on the bottom side of the record, and they frequently get lumpy. I'll stop now to give the Linn-oids some time to fire off protest letters...

There. Do we all feel better now?

And remember: If you try anything other than the felt mat that comes with your Linn, you are subject to having the turntable removed from your home by the Linn police, who will place it in a more deserving domicile. So keep such subversive experiments off the Internet and to yourself!

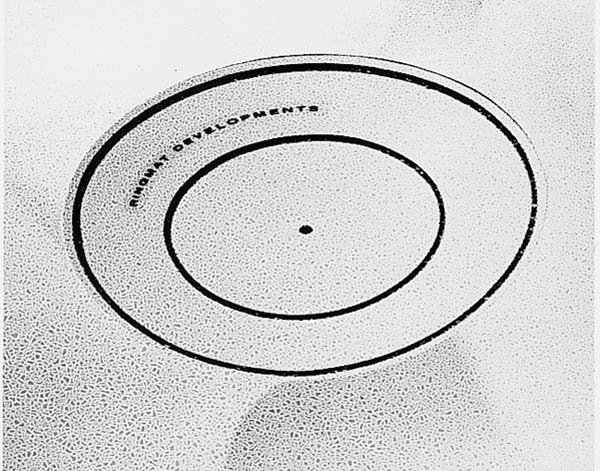

The moderately priced Rotel RP-900 I reviewed last August (Vol.18 No.8, p.47) comes with a felt mat for its glass platter. A while back I received an English product called the QR/DNM "Ringmat''—a heavy paper mat that suspends the record on concentric cork rings, and is designed to replace felt and rubber mats. It's also recommended for acrylic platters that don't require mats.

The Ringmat (there are three versions available for different applications) is a piece of heavy paper of some kind, 91/" in diameter (Footnote 2). There are three thin cork (or corklike) rings on the bottom surface: one on the outer circumference, a second about a half inch in, and a third about 1/8th" from the center hole. The record contacting surface features two thicker rings, one 1/4" from the edge and the other about 1/" from the center. For about $75, it's not particularly attractive, and looks homemade (the packaging is more impressive than the product), but it works.

I preferred the sound of the VPI TNT's bare acrylic/clamp combo to that of the mat with no clamp (as recommended by Ringmat), but I definitely liked the sound of the Ringmat with the Rotel—and I liked the fact that it didn't gather dust. With the Ringmat in place of the RP-900's felt mat, there was a slight improvement in clarity, a satisfying additional fullness and warmth, and a greater sense of "air" and space. Was this an additive distortion caused by the record being more free to resonate when it is suspended on the cork rings? I don't know. The fact is, when you're playing records on budget equipment you're always dealing with resonances and additive distortions. Removing them and/or moving them around is part of the analog game.

Keep in mind that most mat changes affect VTA (vertical tracking angle), which itself can account for sonic changes irrespective of what the mat is doing. Also keep in mind that for a couple of bucks, you could probably buy a sheet of heavy paper, a cork pad, and a bottle of rubber cement, and play to your heart's content cutting out rings. If the rubber cement vapors ruin your records (or your brain), I'm not responsible. And if you're using a Sorbothane or other type of soft mat and it's doing the job for you, don't worry about any of this. (Of course being an analog obsessive, you probably will).

Vacuum-cleaning machines explained!

Vacuum machines? What's there to explain? I went lurking on CompuServe's CEAUDIO forum recently, and when the subject came up, there was a surprising number of messages posted by people who had heard about them, but had never seen one and didn't know how they worked. Today, by coincidence, I spoke with VPI's Harry Weisfeld, who told me he'd attended a record collector's convention near his home recently, where some enterprising guy had brought his VPI HW 17F and was cleaning records for a fee.

Weisfeld stood off to the side and watched at a convention of record collectors as people stopped by, mouths agape, to see a machine suck filth off records. "A machine that cleans records? I've never seen anything like it!" More proof that this industry is in need of some serious publicity. So bear with me here if you're a veteran of the record-cleaning wars.

Leaving aside the expensive and complex Keith Monks unit, which is to my knowledge the original, there are three available cleaning-machine configurations manufactured by three companies. One kind uses a spinning platter like a record-playing turntable, one uses an idler-wheel rim drive to turn the record, and one has you doing the turning by hand.

The spinning platter machines are made by VPI and SOTA (which just entered the market with a unit that looks very similar to the VPI), and the rim-drive and manual models are made by Nitty Gritty.

Regardless of type, all use a velvet-lined slit to vacuum the cleaning fluid off the record. On the VPI units, the slit and velvet pads are part of a spring-mounted clear-plastic tube positioned over the record. On most Nitty Gritty models, the velvet pads and slit are chassis-mounted. One model that does both sides of the record simultaneously, features both a chassis-mounted and a moveable slit/pad assembly.

The cork-mat turntables on the VPI models are powered by what sound like rotisserie motors—high torque and slow turning. To keep the record from being sucked up when the vacuum is applied, it is clamped to the platter via a threaded spindle. The clamp, which is made from a very hard material, will inevitably slip from your hands and slide across the record leaving either a nasty gash or no damage at all, as your heart rises up to your nasal passages.

You will curse and be more careful from then on. Someday, someone will make a soft, rubber-coated clamp for the thousands of VPI machines out there and make some serious pocket change. Maybe it will be VPI, maybe it will be you.

With the record safely clamped in place and the turntable spinning, you squirt the fluid of your choice onto the record, either manually on the $450 VPI HW-16.5 or via the reservoir/hand-pump unit built into the $900 VPI HW-17. You then brush the record, using the supplied stiff brush on the '16.5, or let the built-in one that swivels into place on the '17 do the work for you.

I don't think the HW-17's brush does a good enough scrubbing job, so I advise you to use a hand brush even if you have a '17. And don't be shy: The bristles are softer than the vinyl and, in my experience, will not scratch the record no matter how hard you brush (within reason). I scrub it thoroughly in every direction. The HW-17 can spin in either direction to aid the automatic brushing process, but I still think the hand method works best.

Once you've got the record scrubbed, you rotate the velvet tube into place over the record and flip the vacuum switch. On the HW-16.5 you will hear a very loud noise, so loud, in fact, that as some apartment-dwelling CompuServe respondents told me, they can't use the machine at night lest they wake their neighbors. The HW-17 is much quieter. The heavy-duty '17F model features a fan that allows for continuous use. Hey, you pay, you get, as my grandmother used to say.

The vacuum sucks the spring-loaded tube down onto the record surface, and after a few rotations, the liquid is removed, leaving a dry, pristine surface. The SOTA unit, which I've had no experience with, works in a similar fashion to the VPI '16.5, though it is reputed to be quieter and features a design that, it is claimed, keeps the vacuum pressure even over the entire record surface.

The Nitty Gritty models are more compact, featuring a spindle upon which the record rotates over the velvet-lined vacuum slit. You put the record on the spindle, apply the fluid, and brush; then you turn it over to vacuum. You clearly can apply more pressure on a turntable model. Or you can brush the record on a hard surface first.

After you've brushed the record with the fluid, you turn it over, position the edge of the record into a groove in the rubber idler wheel, and switch on the motor to start the record spinning. The rest of the operation is similar to that of the VPI. You know you've applied too much fluid if, when you turn the record over, your floor gets soaked.

The Record Doctor II, a hand-operated Nitty Gritty packaged for the Audio Advisor, sells for around $00. Two self-spinning models, which vacuum both sides of the record simultaneously, sell for $689 and $789.

I can't see anyone getting into analog without a record-cleaning machine.

The dark side

You will note that the velvet pads on all of these machines are black. Do you know why? Because if they started out white, they'd be black after you cleaned a few records. But what you don't see can hurt your records. That's one reason you should wet-clean your records with record-cleaning fluid first, wiping them with cotton pads; then use an Orbitrac to dry them; and then—and only then—perform another round of wet cleaning and dry them with the vacuum machine.$s3

$M3 Full details of the optimal procedure are contained in a reprint available for $5.00 from The Tracking Angle: Too Many Brochures! Publishing Company, PO Box 6449, San Jose, CA 95150-6449.

If you own a vacuum machine and you've done nothing to clean your velvet pads for the past few years, you are simply sucking up dirt with the vacuum and smearing filth all over your records with the velvet pads! No wonder after you've cleaned a record (or thought you have), your stylus gets gummed up with crap before you're halfway through a side! Cleaning the pads on a regular basis—especially if you vacuum filthy records without pre-cleaning them first—is an essential part of the record-cleaning ritual.

With the VPI and SOTA machines you can remove the armtubes for easy cleaning (you can also order tubes for vacuuming 45s and 78s). What I do is make a very, very dilute mixture of unscented liquid Tide laundry detergent and water. I dip the armtube in it and soak it for about a minute. Then I scrub the velvet pads with a nail brush reserved for just that purpose, after which I dip the tube back in the solution, which by now is the color of New York's East River and twice as toxic. Then it's into a quick bath of steam-distilled water, followed by a good shaking. (Fetishists use semiconductor grade or triple-distilled water, which, in New York City at least, requires a prescription).

To keep the pad from drying stiff, I make another very weak solution of unscented Downy fabric softener. After a quick dip, I brush the velvet with a different nail brush, and then I soak the tube in more steam-distilled water until I'm sure all of the fabric softener has been removed. Then I let it dry. While some purists are probably alarmed by the detergent and fabric-softener routine, I have found that, with proper care, no residue is left. Nor have I ever had a problem with the glue that holds the pads in place letting go.

Footnote 1: Analog fans can contact Michael Fremer at 74032.1717@CompuServe.com

Footnote 2: The Ringmat is distributed in the US by Music Hall, 108 Station Road, Great Neck, NY 11023. Tel: (516) 487-3663. Fax: (516) 773-3891.