I have all these disks. They are awesome. I can listen to music while playomh geometry dash scratch

Analog Corner #12

(Originally published in Stereophile, July 12th, 1996)

There's news on the Exabyte front: In my April column ("Now the Bad News," p.58), I reported rumblings in the mastering community about the growing use of the Exabyte computer backup system in CD production. The 8mm tapes allow glass masters to be cut at double speed, thus halving production time, and time is money so "look at the clock!"—that's for all you My Little Margie fans.

No sooner had the ink dried on that story than I received a call from a Marv Bornstein, who consults for Cinram, an Indiana-based CD manufacturing facility. Bornstein worked at A&M for many years, back when sound quality was job number one there, and Bernie Grundman ran Herb Alpert's cutting lathe. An ex-girlfriend of mine worked at A&M when I lived in Los Angeles, so I got to hang around the lot a lot and I'd actually met Bornstein (and Grundman for that matter)—it's a small platter ain't it?

So happens Cinram presses discs for the BMG Record Club, and among the titles being worked over was the BMG/RCA Victor The Songs of West Side Story Lennie B. tribute album I also wrote about in that column—the one that didn't end up sounding so good despite the Oceanway all-analog production. Anyway, the original of that disc was pressed by JVC, but the Exabyted BMG Record Club version was Cinram's baby. Guess what? According to Bornstein, both Grundman and Oceanway's Allen Sides were quite happy with the Exabyted results that Bornstein sent them, sourced two ways: from 1630 tape and from CD-R.

So whatever's causing stuff to come back from the shop not sounding like the good little digital clone it is, it would seem that Exabyte is not the culprit. Bornstein was kind enough to send me both versions of West Side Story that Cinram cut for Grundman and Sides, which I compared to the JVC original. He also sent me the BMG Record Club editions of the outstanding Impulse! SBM jazz reissues, so I could compare those Exabyted discs with the GRP originals pressed by MCA. Hey! I thought that exercise went out with the death of vinyl!

I'll spare you my findings since this is supposed to be an analog column, except to say if the Cinram edition was mastered from Exabyte, and the JVC one wasn't, Exabyte's no villain. In fact if anything, the Cinram version was slightly better focused at the very bottom, and McCoy Tyner's piano sounded more coherent. (My original Impulse LP creams both of them, of course!) So whatever's causing music to come back shrunk from the CD dry cleaner, it's probably not Exabyte. Case closed (I think).

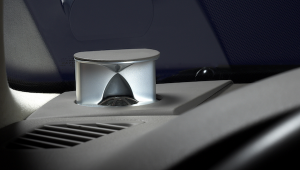

Still relaxin' in camarillo

Talk about having one's ducks in a row: Acoustic Sounds' Chad Kassem has David Wilson's Audio Research tube-driven, tricked-out Neumann SX74 cutting lathe set up at RTI's Camarillo, CA plating and pressing plant. So now veteran mastering engineers Stan Ricker and Bruce Leek can cut a lacquer, take it down the hall for plating, and have a 180-gram test pressing in hand with Polaroid-like speed and convenience (well, maybe not quite that quickly).

So how has Chad Kassem progressed from being a mail-order supplier of RCA "Shaded Dogs" and Mercury "Living Presence" LPs to an award-winning executive producer for his own label (Jimmy Rogers Blue Bird and Nancy Bryan Lay Me Down, both on Analog Productions Originals), a first-class reissuer of outstanding jazz, blues, rock, and classical music on audiophile-quality vinyl and gold CDs, and now owner of a top-shelf disc-cutting facility?

Answer: hard work, and more importantly, a willingness to admit to not knowing everything, and by listening. Yes, Chad does love to talk—you usually have to cut him off in midstream or you won't get any work done—but he does listen. That's obvious from the wide-ranging, often way-out-in-left-field choices in his reissue catalog. There's something for every taste, and beyond that, he offers vinyl fans a chance to explore some great-sounding, out-of-the-way stuff they wouldn't ordinarily hear.

I recently received some test pressings of the first group of Chad's "Revival Series" 150-gram releases, and when they're available, you'll be in for a musical and sonic treat. Kassem has chosen an eclectic mix of well-known and obscure (Sidney Maiden?) jazz and blues recordings for reissue including Thelonious in Action, Monk's first non-studio recording. The mastering job creams both my original Riverside and the OJC reissue.

One thing's for sure: There's nothing soft or "tubey" sounding about the test pressings I received. While each sounded unique, they all shared a few common characteristics: superb dynamics, incredible focus and clarity, and a quiet that'll have you dropping to the noise floor. And at $17.50 you can buy them without gulping.

Between these issues, and Classic's, Mo-Fi's (do not miss Mo-Fi's reissue of Nirvana's Nevermind), DCC's, and all the rest, I'm reaching "critical vinyl reviewing mass"—which means I could spend all of my reviewing time covering just vinyl. Who would have thought this possible a few years ago?

Lacquers for slacquers

At HI-FI '95 in Los Angeles, History of Recorded Sound's Len Horowitz slipped me a promotional lacquer from a company called Transco in Linden, NJ. Horowitz is an analog enthusiast and mastering engineer once employed by Westrex, the inventors of the 45/45 stereo cutting system. Some of you may be familiar with History of Recorded Sound's "direct to lacquer," 45rpm, red vinyl Big Daddy release from 1990, on which the group covered The Cars' "Just What I Needed," Robert Palmer's "Addicted To Love," and a few other tunes, as if they were written and recorded in the 1950s—"doo wop" style. (They did the same to the entire Sgt. Pepper album on a hilarious Rhino CD.)

Anyway, the promo lacquer's color Xerox cover shows three children entranced by a cutting lathe—I assume Horowitz's—in the process of cutting a lacquer. Underneath, it says: "the new generation...Transco." It's been sitting around on a shelf for almost a year, and while I was contemplating Kassem's high-/low-tech assembly line, I thought: "A visit to a lacquer manufacturer! What could be nerdier?!!! And it's only a hop, skip, and an oil refinery away!"

I called Transco immediately and set up an appointment. Transco President Bob Cosulich was solicitous; after all, lacquer manufacturing isn't exactly a breaking story, so it's not every day that a reporter requests a guided tour.

Today, there are two main lacquer manufacturers in the United States: Transco on the East Coast, and Apollo on the West. Apollo's equipment originally belonged to Audio Devices in Connecticut (which also made recording tape with which some of you oldsters are surely familiar). Capitol bought the company and moved the equipment to Winchester, Virginia. When Capitol decided to get out of the business (with the introduction of guess what?), it sold the lacquer manufacturing gear to Apollo, which hauled it out west.

I don't want to get into a discussion of who manufactures the best lacquers, nor did I poll all the usual suspects to find out who supplied their lacquers. I was just curious about how lacquers are made and I was happy to be able to find the answer a car ride away. I will say though, that I've seen both brands of lacquers at most cutting facilities I've visited.

Linden, New Jersey is just south of Newark, in that industrial stretch where you wonder what they were thinking when they nicknamed it the "Garden State" (Footnote 1). Kind of looks like El Segundo, California, but without the ocean backdrop. During the 50-minute ride from home (in the souped-up '72 Saab 96, of course—could you believe Eduardo Benet's letter in the February issue, getting on my case for beefing up the engine?), past Giant Stadium, past the big, stinking oil refineries, past the Port of Newark, IKEA and the International Airport, I tried to imagine what I'd find when I reached Transco.

All I could think of were the abandoned hulks of steel mills you see in the rust belt. I kept fixating on some huge, dark, postwar apparition, mostly empty and cold now but for a small area of activity where a few lonely souls trickled out the occasional lacquer: a far cry from the thousands that used to roll off the assembly lines like Model Ts during vinyl's heyday.

What I found off New Jersey Route 1 was a small, clean manufacturing facility—storefront-sized as seen from the street but actually much bigger—meticulously run by two brothers-in-law clearly more interested in playing golf than playing records. Bob and his partner Fred got involved in the arcane business of record lacquer manufacturing in 1971 by injection: They married the daughters of former Transco owner Chet Conk. Hey, that's okay. These guys know which side their nitrocellulose is buttered on. Make good lacquers or it's back to the public links!

Ah, but I'm being obnoxious (so what else is new?). In fact, according to Cosulich, Conk himself had gotten involved in the business through his brother-in-law, who used to work for Presto, a company that made transcription discs before the magnetic tape era. The two formed Transco and began making their own transcription discs. When tape came into the market, they formulated a lacquer that could be plated, and so survived into the next era.

During the 1970s, Cosulich told me, business was booming. "So things slowed down a lot in the '80s?" I asked. "Not really," he said. Capitol had shut down its Virginia facility and so Transco became "basically the only game in town," running 24 hours a day.

Towards the late '80s, however, business did slow down, so Transco got into the tape distribution business, where it still is. Last year, happily, lacquer sales volume went up, though Cosulich wouldn't divulge numbers. This year, he told me, they're ahead of last year so far. The trend is upward, my vinyl-loving friends!

Slipping discs

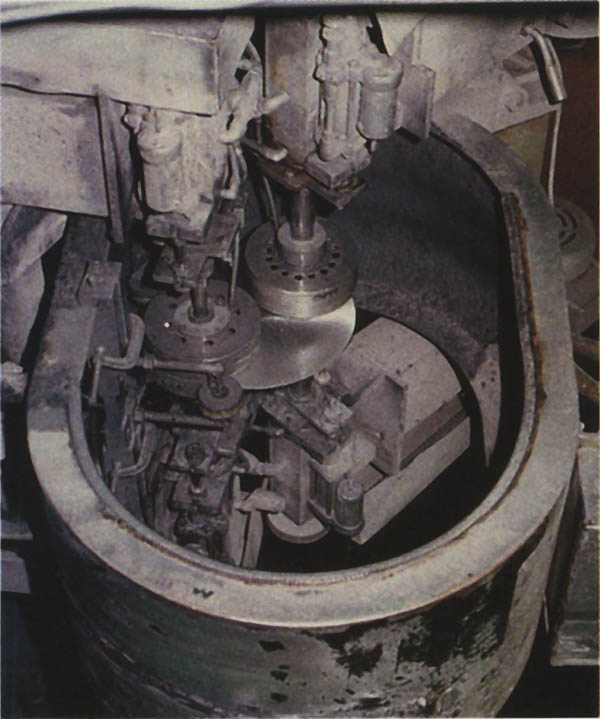

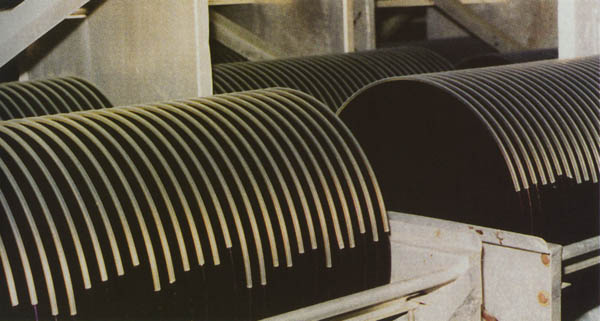

So exactly what is a "lacquer" and how is it manufactured? The first step in preparing a vinyl record is to cut the groove for one side in a perfectly flat disc made by coating an aluminum blank with a thick layer of nitrocellulose lacquer. Bob Cosulich took me on a guided tour and showed me the process, beginning at Transco's other facility a few miles away on the same street. There, aluminum discs are baked into submission in a large oven to make sure they're perfectly flat. Transco buys the 12" and 10" discs in large palettes. Once the discs have been baked and cooled, they're washed and then polished in these giant grinding/sanding machines until they're silky smooth. The equipment is so specialized, Transco has to manufacture its own sanding discs for the machines.

The polished discs are hand-inspected, carefully packed, and driven over to the main plant where the final coating and curing takes place. The lacquer itself is a flammable, explosive, nitrocellulose-based material, pre-mixed with solvents, resins, plasticizers, and dyes to form a Concord-grape–colored ooze with the consistency of honey that Transco buys in 55-gallon drums from Randolph Products, another New Jersey firm.

The goo is pumped into Transco's tanks where it's filtered before application. Excess is pumped back in to the tank, but not before being filtered again. In fact, Cosulich told me, the lacquer is filtered continuously. What else is this stuff used for? A variation makes nail polish, and at one time, pencil and airplane paint were made from nitrocellulose-based lacquer, but no more. Cosulich also told me the formulation used today is virtually identical to what was used during the "golden age" of vinyl, though certain materials have changed due to stricter environmental regulations. I don't know about you, but I'm willing to give up a bit of noise floor to help save the environment.

As you might imagine, lacquer fumes are quite noxious, and Transco is monitored by both state and federal (EPA) environmental agencies, which actually insist that the gases be incinerated rather than be vented into the atmosphere. You know those environmental whackos. Given the added expense, it's a wonder we can still compete against cheap, foreign-made lacquers.

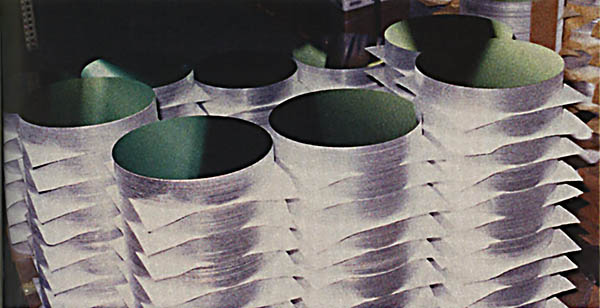

Over at the main facility, the polished aluminum discs are carefully unpacked and run through the lacquer coating machine that applies a thin coating to one side. Once out of the machine, the lacquers are carefully stacked to cure for a few days. Then the process is repeated to coat the other side. The double-coated lacquers are then put in a dishracklike device and filed away for a few weeks of final curing. After the curing process is complete, the lacquers are carefully boxed and shipped off to disc mastering houses around the world.

Of course there's QC. Cured lacquers are tested by the batch for noise on Transco's in-house lathe. Silent grooves are cut and played back. Rejection rates are low, according to Cosulich, mostly because everything is carefully monitored during each step in the procedure, and Transco's been at this for a very long time.

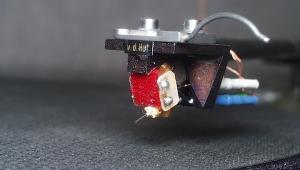

Another part of Transco's business is manufacturing cutting styli for every brand of cutting head: Westrex, Ortofon, Neumann, you name it. It's a very specialized skill that took about a year to teach to the Transco employee who now does it pretty much full time.

So that's the lacquer story. I want to thank Bob Cosulich for taking a half day out of his busy schedule to show me around his facility. By the way, if you think records sound like dynamite, you're not too far off. Nitrocellulose is explosive, so if you have a stock of lacquers, keep them locked up and out of the hands of your local militia, or they may be ground down for pipe bombs!

Like a mega-virgin

The evening before my lacquer excursion I attended the pre–grand-opening party for Virgin's new Times Square MegaStore, said to be the world's largest "record" store. With press badge in hand I entered early so I could explore and shoot pictures before the hordes of invited guests packed the place and obscured the view.

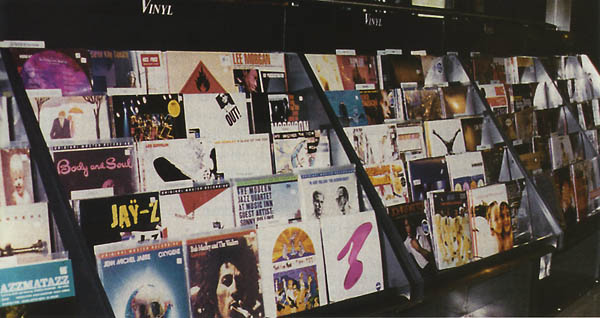

This is one giant multifloor extravaganza! With over 150,000 CDs, 7000 laserdiscs, I don't know how many audio and video cassettes (who cares?) and a promising, though not particularly thorough, vinyl section; a book store; a cafe; a performance stage; about a hundred listening stations—even some video software viewing stations—and a Sony multiplex movie theater in the basement, you could spend the day and not see it all.

By the eighth glass of champagne I wasn't seeing much anyway, but before the libations and the hors d'oeuvres turbo-charged their way through me, I did manage to get some pictures and take some notes. The store is very well-organized by format and musical genre (there's even a "Vintage" section for '50s rock) and very well-stocked, with a good mix of imported CDs and LPs, and lots of independent and out-of-the-way stuff (on CD). The box-set selection, however, was not up to snuff (store reps told me that stocking was far from complete). Back catalog depth was also pretty good and the shelf design made for easy pickin's.

One thing that really impressed me: The CDs in the listening stations and on the feature racks above the bins seemed to have been chosen as much by the enthusiasm and tastes of the section managers as by record-label strong-arm marketing tactics. That's good! It helps give the store a unique personality. None of these chain stores have the charm of independently owned "mom-and-pop" operations, but it seemed as if whoever was in charge of the Virgin operation was allowing the underlings to express themselves—at least on a limited basis.

The listening stations, by the way, were very well-organized, flexible, and easy to use. Each station offered a choice of four discs, and you could choose any selection on each. With high-quality Sony headphones at each station, and lots of volume, fidelity was pretty good. I auditioned discs I knew (like Jonny Polonsky's short but sweet pop masterpiece on American Records) to see how they sounded. Verdict: good enough to tell whether or not the recording was decent.

As an experiment I chose a musical title in my collection to see how long it would take me to locate it in the store. Not bad. And they'll order anything not in stock on CD or vinyl, domestic or imported.

But aside from the improved selection of vinyl—enough to get me to return; in fact, had the registers been open that night, I would have spent plenty on imported and domestic vinyl—and the sheer volume of CDs, did anything really distinguish the Virgin MegaStore from other record stores?

Not really.

A while back in this space I wrote about the folly of stores mixing expensive gold CDs in with the regular product. Unfortunately, Virgin makes that mistake. By chance, I happened upon the example I used in my column: Back to-back in the Bob Marley section were both Polygram's $8.49 CD of Exodus and Mobile Fidelity's super-sounding gold CD at PRICE???. Which do you think the uninitiated would buy?

My feeling is: As long as you're going to stock audiofool goods, have an audiofool section with both gold CDs and thick vinyl. Instead, the Mo-Fi and Classic Records vinyl was mixed in with the regular stuff in the curvaceous vinyl section. Didn't see no DCC vinyl (or gold CDs for that matter) or any of the other audiophile vinyl we know and love.

Speaking of the vinyl section, it was a curious grab bag: lots of great imports of stuff unavailable on domestic vinyl like Björk's two solo albums—the second one's on pink vinyl—and the usual suspects (Kiss, My Ass on colored vinyl, Bruce Springsteen's Greatest Hits, etc., and lots of Mo-Fi product, but very little independent label domestic vinyl, which is where most of the interesting action is—though I did spot Everclear on Tim Kerr Records. (The CD is on Capitol.)

There's also an entire section of 12" dance singles and an almost hilarious $2 and $3 cut-out bin, which contained LPs probably locked away in Virgin's English basement for a decade. (Wham! anyone?) On the other hand, some of the English cut-outs, like some old Graham Parker albums, were really tempting.

It was clear to me that the staff at the Virgin MegaStore does not include anyone hip to the current vinyl scene. Too bad. Maybe that will improve. At least they're trying.

Meanwhile, if you visit the Big Apple and you're searching for vinyl, make sure to visit Other Music across the street from the downtown Tower, on Fourth and Broadway. They have a superb selection of indie music on vinyl.

Footnote 1: As a New Jersey resident, I think the "Garden State" sobriquet refers to the vegetative state the New Jersey electorate was in when it elected Christie Todd Whitman Governor.

- Log in or register to post comments