Analog Corner #24

(Originally published in Stereophile, July 12th, 1997)

Here's a great garage-sale find: a series of 7" 331/3rpm records sent by a drug company to doctors during the late '50s. Knowing that many doctors back then were classical-music aficionados, the company would put a licensed excerpt from labels like Vanguard and Westminster on one side, and on the other a medical lecture extolling the virtues of the drug it was pushing. My favorite: John Philip Sousa's "The Thunderer" paired with "The Treatment of Some Gastro-Intestinal Disturbances."

Flash! The record biz's savior has been announced, and you're reading it here first. According to some statistics, the prerecorded music industry saw sales drop a precipitous 30% last year (Footnote 1). Why? Well, there are many reasons why CD and cassette sales dropped and why vinyl was the only format to show an increase, but the industry, noting the trends, has decided what needs to be done to increase sales this year.

And the winning solution? "Bring back the cassette!" I kid you not. A group within the record industry has decided that emphasizing expensive CDs and downplaying inexpensive cassettes have driven away a large portion of the market who cannot afford CDs. So a newly formed organization called the Audio Cassette Coalition has been formed to "revitalize" the cassette market.

Never mind that vinyl is the only format to actually grow last year, despite the industry's decade-long campaign to kill it. "Some see [the cassette] as nostalgia, while others see it as a smart way to address more than 30% of the music-buying public that is not being served." So says an article in Replication News, a publication serving the mastering and duplication side of the industry.

Not being served? Last time I looked, cassettes were all over the place—at every store. People just aren't buying them. Records are impossible to find, but people are buying them. "Nostalgia''? Yes, let's go back to those wonderful days of prerecorded cassettes. Remember the sumptuous packaging? The steel-jaw hinged cases? The sturdy cassette shells packed with high-quality tape? The great cassette sound? I know I don't.

The same issue of Replication News contained an informative article by one Dave Moyssiadis, an engineer who is very disturbed about the vinyl resurgence. For those reading his column who haven't heard vinyl, Mr. Moyssiadis gives them a taste by telling them to compress a piece of plastic shopping bag in one hand and let the bag decompress while they play a $150 CD player. As the disc plays, turn the treble "down so that it is almost all the way down by the end of the CD, all the while kneading the plastic." Mr. Moyssiadis also "doubts that many consumers will notice the difference between 16-bit and 24-bit, and 44.1 and 96[kHz sampling]." I can't notice the difference between Moyssiadis and a [insert analogy here].

Actually, his column is a good sign. Only when people are genuinely threatened do they resort to this level of disinformation and outright distortion. Clearly, the vinyl resurgence is disturbing to the guy. Have a nice day, Dave! By the way, through his editor at Replication News, I've invited him over for a listen and some serious "A/B''-ing. I doubt he'll take me up on it. For some people, the truth is too painful.

Staying dead

So we're turning in late at night last weekend and I flip on the television to Time-Life's "Disco Years" (or whatever it was called) infomercial. They're showing all these great mid-'70s discotheque clips (you can almost hear the off-camera sound of razor blades scraping mirrors), and the announcer says something like, "You remember those great dance tunes on your old vinyl records, don't you?" With that, he plops the arm of a Technics SL-1600 disco 'table onto a record and this totally manufactured sound comes out: everything's rolled-off above, say, 3k, and they've artificially inseminated the mix with pops, clicks, scratches, and what sounds like a snowplow dragging on cement at a ridiculously high level.

"Now, here's that same music on CD!" And it's perfect sound forever—of course! So annoying, so deceptive—the last thing an analog geek wants to experience before sack time, but there it was. The only way I could sleep was to resolve to do something about the outrage first thing Monday morning.

I called Time-Life Music headquarters and tracked down an executive in charge, who shall remain nameless. I left him a very nice voice-mail message: "Hi, this is Michael Fremer. I write for Stereophile magazine and I edit a magazine called The Tracking Angle and I'd like to talk to you about the Time-Life disco infomercial I saw on television last weekend blah blah blah."

A few days later I get a phone call from the guy: "Hi, Michael? This is [deleted]. Got your message. I was really surprised to hear from you! I read your column in Stereophile and I also get The Tracking Angle. I'm an analog listener. I've got a Rega Planar 3/Blue Point combo! I don't go for CDs myself."

"Well then how can you run such a deceptive ad? At least put a disclaimer at the bottom saying that the sound demo is simulated!" I was jumping out of my skin.

"Well, you know, the ad isn't aimed at you; it's meant for Joe Sixpack in Chattanooga who's got a plastic turntable and whose records do sound like that."

Normally I wouldn't accept such an answer, but the guy flattered me. Flatter me and I'll follow you anywhere.

Groovy CDs

Last week I visited Warner/Elektra/Asylum's LP/CD/DVD pressing plant in Olyphant, Pennsylvania with mastering engineer Greg Calbi (a zillion great credits) and record producer Craig Street (Cassandra Wilson, Holly Cole, the new k.d. lang album, etc.). Never have two and half hours in a car gone by so quickly or been such fun. I could spend a whole column on the car-ride conversation and the plant visit (maybe I will in the future). The tour of the facility was fascinating and informative, and if you think "bits is bits" and CDs are inherently "perfect" sonic duplicates of the original digital master tape as long as the numbers are all there, you really don't know what you're talking about. Do yourself a favor and talk to the folks doing this every day. You'll learn something.

One of WEA's optical engineers showed us how glass mastering works and, using electron-microscope images, what "pits" and "land" surfaces on CDs look like. He also showed us a new mastering technique being used by Nimbus that WEA is interested in, in which the spiral of pits tracked by the laser is connected by—are you ready?—a groove. This makes it easier for the laser to track the spiral, and translates into better sound.

I figure next they'll fit the laser with a tiny stylus that'll track the groove better. Then they'll widen the groove and include some modulations for the stylus to follow that will smooth out the transition from land to pits. Then they'll widen the groove and make the stylus bigger. Then they'll get rid of the pits and just stick with the modulations in the groove. Then they'll get rid of the laser...

Chesky RCA vinyl: last call

Chesky Records began the RCA vinyl reissue business years before Classic Records got into the act. They didn't have the rights to the original covers, but, like Classic, they did use the original master tapes. Many were mastered by Tim de Paravicini using an all-tube cutting system. Some audiophiles prefer the warmth of the Chesky RCA issues to the clarity and detail of the Classic versions. Though this is neither the time nor the place to enter into that debate, Chesky's licensing agreement expires at the end of the year. This is last call on the Cheskys.

There are limited quantities available of these 10 titles: Scheherazade (Reiner/CSO, Chesky RC4); Pines of Rome/Fountains of Rome (Reiner/CSO, Chesky RC5); An American in Paris/Rhapsody in Blue (Wild/Fiedler/BPO, Chesky RC8); Spain (Reiner/CSO, Chesky RC9); Lieutenant Kije/Song of the Nightingale (Reiner/CSO, Chesky RC10); The Reiner Sound (Reiner/CSO, Chesky RC11); Daphne et Chloé (Munch/BSO, Chesky RC15); The Power of the Orchestra (Leibowitz/RPO, Chesky RC30); Pastoral (Reiner/CSO, Chesky RC109); Gaîtè Parisienne (Fiedler/BPO, Chesky RC110).

The records are available at many audio stores, or directly from Chesky for $24.98 each by mail. Call (800) 331-1437. In New York, call 586-7537. I suggest getting at least one so you can compare it to the Classic reissue and decide for yourself which sounds "better," "more like the original," etc.

The Psychology, physiology, & mechanics of cartridge alignment

If you've got a turntable and you've relied on your dealer or a friend to do your setup, you're living with your hands tied behind your back. Knowing how to align a cartridge is really a necessity for any analog-loving audio geek, and it doesn't have to be difficult or traumatic unless you choose to make it so.

If you're a jerk, setting up a cartridge can be problematic, so stop being a jerk. Today "jerk" is an all-purpose derogatory term, but originally it described someone who "jerked" abruptly from one movement to the next. Let's say you're trying to install a cartridge and you've got your hands full. The phone rings, or someone knocks at your door. If you "jerk" in response, you'll probably lunch the cantilever. Don't be distracted!

Or let's say you're trying to get the nut on the end of the screw and it falls off onto the floor and you "jerk" to grab it. Same result: lunched cantilever. When doing an install, it's best to be in a relaxed state of mind when you start, and to not let outside stimuli or that inner negative voice (usually an imaginary parent looking over your shoulder and calling you a useless klutz) cause you to "jerk." If you keep your eye on the prize and don't worry about making a mistake, you won't "jerk," and you won't ruin your cartridge.

Let's do an install. Keep in mind that there are many ways of doing this, some more fanatical than others—and some larded with mystical bullshit. I'm not as obsessed as some, and yet I get what I think are very good results. Start with a clear head. Don't drink, smoke, or even eat right before you attempt to install a cartridge. Don't do it wearing a long-sleeved shirt with floppy cuffs that will end up catching on something. Wear a T-shirt. Don't do it when you're pissed off about something or at someone. Don't do it when you're distracted or short-tempered. For me that means a narrow window of opportunity, but I wait for it before starting.

Installing a cartridge is like cooking in a wok—you want to have all of the ingredients in front of you and well organized before you heat up the oil. Otherwise you, your food, or both will get burned. If you can move your turntable, put it on an empty table in a well-lit room, preferably one without plush wall-to-wall carpeting.

Have the following close by: a stylus-pressure gauge; a cartridge alignment tool; a few small rubber or wooden wedges; a good pair of tweezers or a small, high-quality, flat-blade needle-nose pliers; a small slotted screwdriver or a hex wrench (if you're using hex-head cartridge screws); high-quality, nonmagnetic cartridge screws (and nuts if necessary); a high-quality magnifying glass; a small flashlight and/or a goosenecked Littlelite;r; and a bubble level.

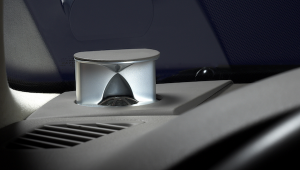

The Shure pressure gauge is reasonably accurate, and it's a bargain at under 20 bucks. Which alignment gauge should you use? Many cartridges and all of today's finer arms come with an alignment tool of some sort—everything from a piece of paper to a laser-etched piece of glass. DB Systems makes a good one, there's MoFi's Geo Disc, and, if you're on a budget, Lyle Cartridges makes an easy-to-use plastic one that's reasonably accurate. Townshend Audio has been threatening to produce one for the past two years—they keep calling me about it but it never arrives. Perhaps it'll be available by the time you read this.

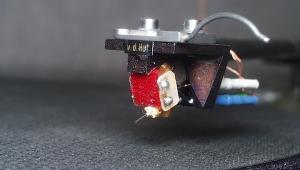

With the stylus guard attached (or with the stylus removed, if you're mounting a moving-magnet cartridge) and the arm locked in the rest, use the tweezers or small flat-blade needle-nose pliers to slide the arm's wire clips onto the cartridge pins: Red is right "hot," green is right ground, white is left "hot," blue is left ground. I find it much easier to connect the wires before attaching the cartridge to the arm. Dress the wires neatly so they're not crossing over each other on their way to the pins. Never use your fingers to do this, and don't squeeze the ends of the clips with the tweezers or pliers or you may deform the opening.

Unfortunately, pin/clip size hasn't been standardized, so you may run into problems right at step one. If the clips fit too loosely over the pins or slide right off, you're going to have to squeeze them ever so slightly to make them fit snugly. Go easy! If you flatten one out, try using a round toothpick to open it back up. Ditto if the clip won't fit over the pin to begin with. Don't try forcing the clip. In fact, don't try forcing anything during the entire setup procedure!

Once you've got the clips secured to the pins, it's time to mount the cartridge to the arm (unless you've got a removable headshell or a Graham arm). If your cartridge body contains threaded holes, life is sweet, both because it makes the job much easier and because you obviously can afford a high-priced transducer—none of the inexpensive cartridges offers such luxury.

Make sure the screws you've chosen are long enough to go through both the headshell and the cartridge-body flanges, and that the ends stick out far enough for the nuts to grab, but not so far that the screws go below the cartridge body. On some cartridge designs like Grados and Audio-Technicas, which have short flanges, this won't be a problem; what will be is maneuvering the nut in position next to the body. It's tricky and frustrating, and the nut will probably fall and disappear under a chair. Don't jerk when it falls!

How I do this: I insert the screw in the headshell and then through the cartridge flange. Holding the cartridge up against the shell with one hand, I put the nut on the tip of the other hand's index finger and push it against the bottom of the flange. I then use that hand's thumb to clamp the whole thing together, which frees the first hand to grab the small screwdriver I've left close by. Then I turn the screw while pushing on the nut with my index finger. That usually causes the nut to grab and begin to thread. Tighten only as far as needed to prevent the cartridge from sliding forward and back. The other screw will be much easier to thread.

Next, slide the cartridge forward and back until it's about midway in the headshell slots. If it's a MM cartridge, replace the stylus assembly. Before you proceed, remove hairy and rubber mats so the stylus will see a smooth surface. Use the small rubber or wooden wedges to prevent the platter from spinning.

If you're using a Rega arm or one of the others that has a built-in gauge, set it to zero and move the counterweight forward or back until the arm just floats. Now set the tracking force to the midpoint of its recommended setting range. If your arm doesn't have a gauge, back off the counterweight until the arm floats, then move the counterweight forward until the arm just drops. Now use your gauge to set the VTF (vertical tracking force). Using the Shure fulcrum gauge is pretty much self-explanatory—just make sure the stylus is in the gauge's groove, and be careful when you first lower the stylus in case you've got the pressure set way too high. Use the cueing lever; if the gauge drops like a stone, raise the lever quickly and back off the weight a bit.

Each time you do this, return the arm to the rest and secure it. Don't try to hold it over the gauge while twisting the counterweight. Get in the habit of being extra-cautious at all times and you'll never lunch a stylus. Keep your eyes on the prize! Never look away for something else while your fingers are in close proximity to the stylus. That's why all tools and accessories should be within your peripheral vision while you're doing the install.

Once you've gotten the fulcrum to balance at the correct weight, you're ready to adjust the "overhang" with your gauge of choice. The overhang refers to how far past the center of the spindle the stylus extends in its arc across the record, referenced to a straight line drawn from the spindle to the record's outer edge. Records are cut on a straight line. Pivoted arms describe an arc. When the overhang is set correctly, the stylus intersects the straight line in two places perfectly tangential (ie, a straight line front to back) to the grooves.

If you're using the Geo Disc, or any other gauge that references the arm's pivot point, remember that it's only as accurate as your ability to line up the pivot point. Aim carefully!

One of the most useful, easy-to-use, and inexpensive gauges is the one Lyle Cartridges sells. It features a mirrored surface and a hole for the spindle. Whichever gauge you use, the principles and procedures are pretty much the same; if you're using something other than the Lyle gauge, you'll have to extrapolate.

Virtually all of these devices feature a grid or grids with a dimple or circle representing the spot where the stylus should sit. The Lyle and other similar gauges have two such grids and center points. When the overhang is correct, the stylus will be centered in both circles, and the cantilever's zenith will line up with the grid's front-to-back lines, thus ensuring the cantilever's tangency to the grooves at those two points.

After placing the gauge over the spindle, start at the outer grid and gently lower the arm onto the grid. Carefully maneuver the stylus tip as close as possible to the center circle. It will rest in front of or behind the circle. This is where a Littlelite or small flashlight and a good magnifying glass are crucial. Work slowly and carefully, lifting the arm and moving it back to the armrest before sliding the cartridge forward or back.

This is where how tightly you've snugged down the cartridge is critical: too tight and you can't move it, too loose and it won't hold its place, just right and you can move it and it will hold its place. Then move it back to the gauge and check your progress. Yes, it's frustratingly slow and tedious, but you must be patient. Don't take shortcuts here or get annoyed!

When you get the stylus into the magic spot, you're still not finished. Looking from dead-on straight in front of the cartridge so you can't see either side of the body, look to see that the cantilever is precisely parallel to the hashmarks running in the direction of the grooves, and actually blocks the single line intersecting the stylus tip. If it's angled one way or the other, carefully rotate the cartridge body on its zenith axis (around a vertical line drawn through its center) until you achieve tangency with the line. Don't "wish" it correct—make it so! When you rotate the body you may accidentally upset the overhang. Be sure both overhang and zenith are precisely correct in the first set of hash marks before moving on to the second.

Repeat the procedure with the second set of marks; if you're lucky you won't have to change a thing, but most likely you'll have to shift things a bit until you achieve perfection in both grids. Lock the arm in the rest and use the tweezers or pliers to hold the nut while you tighten both screws. How tight? Tight, but not so tight that you deform the cartridge body. Let's say snug. Very snug.

Now adjust your tracking force to the top end of the manufacturer's recommended range. Then go back and recheck the overhang and zenith. Why? The cartridge may have moved when you were tightening the screws, and if you had to increase VTF you've deflected the stylus slightly forward.

If the stylus is not exactly where it belongs and the zenith is not precisely correct, do it again. Then recheck the VTF. When you're certain everything is where it belongs, you're almost done.

All that's left to set are VTA (vertical tracking angle), azimuth, anti-skating, and damping—if you can adjust those on your arm. And you should fine-tune the VTF by ear within the recommended parameters. I'll go over these parameters next month and describe what you should be hearing if everything is correct, but meanwhile, please remember: While it's critical to do all of this precisely and carefully, in the words of a well-known turntable manufacturer, don't make yourself crazy!

There are audiophiles who change VTA for every record, every pressing, every record label, pressing plant, etc. I'm sorry, but life is too short, and there's too much music to listen to, to obsess like that. I'm pretty particular, and I don't do any of those things. Once I've dialed things in, I leave them alone. I adjust VTA for 180gm records but I have no problem playing thinner ones—they sound fine. If you want to go tweaking VTA for every record, enjoy yourself. Once you've "locked in" a cartridge, you'll know when you haven't—I promise!

There are many variations on this theme—and I'm sure I'll be hearing about them from readers who may be more tweaky than I am, or who have some different ideas on setup procedures. I'll be happy to pass them along.

Footnote 1: According to the RIAA's official figures, the sales of prerecorded music in 1996 were only slightly different from those in 1995, which itself had been a record year. However, according to articles that have appeared in Musician, The Washington Post, and The New York Times, among other places, the record industry is in a world of hurt right now. Certainly, record retailers are having a very hard time of it.—JA