Analog Corner #25

(Originally published in Stereophile, August 12th, 1997)

To paraphrase one of America's greatest living patriots: Extremism in the defense of vinyl is no sin. Okay, my hyperbole may have gotten the best of me when I wrote, in my March column, "The miracle there, of course, would be if the [Disc Doctor's CD cleaning] fluid could somehow make listening to CDs enjoyable''—for which Robert Harley took me to task in his May "As We See It." According to Harley, this is "an extremist position that doesn't take into account the great strides CD sound has made in the last few years."

Well, when I wrote that CDs sounded awful, and that digital recording was a complete disaster back in 1984, "extremist" was one of the nicer things I was called by a bunch of money-hungry opportunists on whose checklists music came last. Why worry about sound and music when the new format meant there were new labels, magazines, and newsletters to start, new pressing plants to build, and a few million recordings to sell all over again? Only an "extremist" would swim against that tide—especially during the "go-go" '80s.

I remember, back then, reading a quote in Billboard from a very famous LA recording-studio owner endorsing Sony's newest digital multitrack recorder as being the best-sounding piece of audio gear he'd ever heard. It struck me as odd, as I'd never heard of a studio owner taking sides like that—especially since there were so many brands of recorders in use back then, with most engineers having their own preferences. A few weeks later, that same studio owner was named the West Coast distributor of Sony digital recorders.

Yes, CD sound has gotten better, much better over the past few years—no thanks, of course, to those who only listen with their test gear. It's become tolerable, listenable, and at least musically credible, but enjoyable? Call me an extremist (no problem!), but for me the answer is still "no." I still cannot sit down, turn the lights out, and "enjoy" listening to a CD.

Is it because I'm hopelessly prejudiced, and in a blind test I'd have no problem listening to a CD all the way through? Maybe, but I think not. When I want to enjoy listening to music, I slap a record on my turntable and kill the lights. I restrict my CD listening to background music, or to listening in the car. That's how I listen to music unavailable on LP.

Someone at Stereophile made the CD of Patricia Barber's Cafe Blue a "Record 2 Die 4" and extolled the virtues of the sound. Sorry, but I did not, and can not enjoy listening to that CD. Then the LP came out, cut from the digital master. That I enjoy listening to. It sounds like real music. The CD sounds edgy, hard, and flat in ways that real music (or, I'll bet, the digital master tape) does not—on every processor I've heard it on. As Bob Harley wrote in that same May column, "[CD's] distortions become inextricably woven into the musical fabric." That, for me, is a fatal flaw. For others, not. I don't think that makes me an extremist.

A few years ago vinyl was almost extinct. Today, though the LP is on the road to recovery, it's still an endangered species. The fight to preserve, protect, and defend vinyl continues, and if that means bashing CDs to get some audiophiles to sit down and listen to vinyl to encourage them to take the plunge, so be it. End of sermon.

Sorry, sold out!

I haven't tried it, but scoring a bag of heroin is probably easier here in the suburbs than buying new vinyl. Mail-order beats driving into Manhattan. Valley Record Distributors, a "one-stop" wholesaler in Woodland, California, has gotten into vinyl distribution in a big way. If you can't find a new commercial title in your neck of the woods, you can order directly from Valley by calling (800) 888-8574 and paying with a credit card. I get sent their monthly LP release sheet so I can keep up with what's being issued on vinyl—it's almost impossible otherwise, since major labels keep their vinyl releases "secret." I guess they're ashamed or something.

A few weeks ago I read that the new Son Volt (Warner Bros.) and Jayhawks (American) albums had been issued on vinyl and were available through Valley for $10.98 each. So I called to order right away. Guess what? The woman who took my order told me, "Sorry, they're sold out." "Sold out?" I replied. "What is this? A concert or a record album? Since when is a record 'sold out' the week it's released?" Well, since vinyl became an endangered species.

Still, Valley's catalog is filled with good commercial vinyl issues—like most of the later Warners R.E.M. albums and Primus' Pork Soda, for example. I'm not sure if they'll send you their vinyl catalog, but if you know something's been released on vinyl and you can't find it, it's worth giving them a toll-free call.

One reason LPs get "sold out" quickly is because the labels are unwilling to press enough copies to meet demand. Instead they do a run of about 2000 and that's that. One reason, at least for WEA, is they can't keep up with the demand. A spokesperson (who wished to remain anonymous) at their plant in Olyphant, Pennsylvania told me that they're 600,000 records behind schedule. You read right: 600,000. So once they've pressed 2000 of a title, there's no way they can go back and press it again—it's on to the next number.

Much of it is 12" club music, but so what? As long as the presses are kept fired up and running, vinyl stays alive at WEA. In fact, they're so far behind, the plant is actively looking for more presses to add to the production line. Who would have imagined that a few years ago? The spokesperson told me the closest they could find presses in good operating condition was in South Africa! That's because dummies in this country thoughtlessly destroyed most of ours. I told the guy to call Mobile Fidelity.

For Sale: 1000 Mantovani albums!

Reissuing LPs is a dicey business: Hit the right title and you can sell enough to make a profit. Do a clunker and you end up with a stack o' landfill. MoFi discovered that, and so did Classic. I don't have the sales figures, but I'd bet Peter Frampton Comes Alive, which sold a gabillion copies in 1976, didn't exactly fly off the Petaluma shelves. Nor did Classic's Eno/Jah Wobble Spinner. In an international vinyl market, safer bets are made reissuing jazz and classical titles, which have worldwide appeal.

When I was in Frankfurt, Germany a few weeks ago attending a hi-fi show, one German reissue-label head (who shall remain anonymous!) told me he was considering reissuing a Bert Kaempfert ("Afrikaaner Beat," "Wonderland By Night'') album, not because Bert was big in Germany but because he was "big" with audiophiles in the States! I quickly disabused him of that notion, thereby saving him both money and personal embarrassment.

I was too late to reach another German reissue-label head, who decided a few years ago that what you and I wanted was...Mantovani. He pressed 2000 copies of Mantovani's The American Scene (London PS 182)—an album of string-drenched Stephen Foster favorites and 19th-century Americana—but to date he's sold only 1000. "Zet's nut goot!" he told me. No kidding, but is better than I would have believed. Anyway, he handed me a copy and told me to go forth in America and spread the word about how good the record was.

I'll say this: the sound is spectacularly good. Sinfully rich and natural-sounding-and what soundstaging! What imaging! What schmaltz! So if "My Old Kentucky Home," "I Dream of Jeannie," "Home on the Range," and "Turkey in the Straw" are your thing, this'll grease your chicken. Hey, if audiophiles can sit and listen to Scandinavians play Dixieland, or get wowed by Bang, Baa-rOOM and Harp, who's to say a little patriotic Mantovani is off-limits? The biggest difference between Mantovani's Stephen Foster and some of the latest Palace Music album (Drag City DC 110 LP) are the strings. Available from your favorite mail-order record dealers. Tell 'em Mikey sent you.

What's in a record?

A few columns ago I asked you to tell me what strange things you've found tucked inside of used records you've picked up at garage sales and flea markets. Love letters and concert-ticket stubs were often mentioned, but the most common discoveries were illegal: marijuana seeds and roaches. Still smokeable? No one said. Those are items I've yet to find in my used-record hunting.

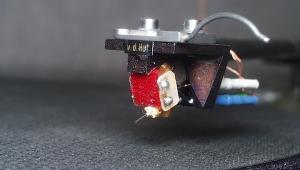

Cartridge Alignment, Part 2

In the July "Analog Corner" I described pain-free cartridge alignment, stopping short of VTA, azimuth, anti-skating, and damping. So, assuming your arm allows for these things, let's get on with it.

Setting VTA is a trial-and-error thing that causes many audiophiles a great deal of anxiety. There is a way around the trial and error, but that won't happen until we get a test record. (Stan Ricker came up with the idea a few years ago, but never pursued it.) Basically, you'd record a vertically modulated out-of-phase tone using all of the known audiophile lathes currently in operation. In other words, Bernie Grundman would do it on his lathe, send the lacquer to Doug Sax, who'd send it to Acous-Tech, who'd send it to the German cutters, etc. Once that was done, the record would be plated and pressed on 180gm vinyl, and you'd play back the track cut on the lathe that cut the record you want to play back, putting your preamp in mono or using a $Y connector. You'd adjust VTA until the signal "nulls" out, and you're right on the money!

There'd have to be another record pressed on thinner vinyl for regular commercial releases, and lathes at Masterdisk, Sterling, Gateway, and the other mastering houses would have to get involved; but as none of this is likely to happen, it's back to trial and error.

Most reviewers have a favorite record for setting VTA. Bob Reina uses a Concord Jazz Rosemary Clooney album, I use Joni Mitchell's Blue—a suggestion I picked up from Fi's Fred Kaplan when we were both at The Abso!ute Sound. Whatever record you use, try one with a clean, natural recording of acoustic bass and female voice—preferably one that's minimally miked and recorded "live," either in the studio or in concert. Start with the arm parallel to the record surface. (This is a very subjective visual thing. The only way to get it right is to view the arm directly from the side, otherwise the eye will be fooled by the change in perspective.)

If you listen mostly to 180gm records, or if those are the ones you listen to most critically, use one for this adjustment. If you really want to get crazy, use a record you don't care about, and with a small ruler carefully measure the record/arm clearance at the headshell end of the armtube and at the back of the tube near the lead-in groove, but past the raised lip. When the height is the same at both ends, you're ready to rumble.

Listen carefully to a few tracks with the arm parallel to the record. Note the soundstage picture and placement of images across it, and the depth generated. Listen to the purity of the vocals, paying particular attention to sibilants, and the sense of "body" connected to the voice. Listen to the articulation of the bass—the focus, the initial transient of the string being plucked, and the resulting rendering of the harmonic envelope as the wooden body reverberates.

Once you've absorbed what should be pretty good sound, screw it up completely by lowering the VTA until the arm is clearly down in back. Check your tracking force and adjust if necessary. Listen again and you should hear the bass turn into a muddy, sloppy mess. If there's more than one bass instrument in the arrangement, as on Janis Ian's "Ride Me Like a Wave" from Breaking Silence—a great test record, by the way—the distinct timbres and spatial specificities of both instruments should blend into an undifferentiated blob.

Images on the soundstage should now be bunched up toward the center and flattened against the speaker surface instead of floating in space. Distinctions between events and ambient decay should be somewhat confused. Vocals should be lifeless, and the image should lose focus. What a mess! If you hear none of this, back to Stereo Review with you!

Now go extreme in the opposite direction by raising the back of the arm way above parallel. The sound should now be bright and hard. Female voices should be shrill, hard, and without body. Bass should sound thin and bereft of rich overtones. If you like this kind of hard, etched sound, find a vintage CD player, some early CDs, and knock yourself out. Just keep some hankies handy to catch the blood dripping from your ears.

Now that you understand the two directions, go back to the center parallel position and begin moving down in very small increments. I (and most reviewers) have found that slightly below parallel seems to be ideal for most moving-coil cartridges. If you hear no differences as you make these slight changes, go back to parallel and stop obsessing! Most experienced listeners can hear these slight changes, though, and there's usually one magical spot (technically called the "G" spot) where everything suddenly locks into focus: the soundstage breaks free of the loudspeakers, images become three-dimensional and intensely focused in space, the ambient field separates from the main event—the full audiophile analog wet dream.

Setting azimuth (the cantilever's perpendicularity to the grooves) reopens an "Analog Corner" can of worms—if you read Ayre Acoustics' Charlie Hansen's letter in November 1996 (Vol.19 No.11, p.16). Ideally, like Charlie, we should all have cartridge analyzers, or oscilloscopes and a test record with modulations in one groove only. You then adjust for minimum "crosstalk" on the channel with the unmodulated groove, and you're done. But in the real world, few of us have either the test record or the oscilloscope. So we're back to the out-of-phase/null method as a starting point. Actually, the true starting point is setting the azimuth by eye so the cantilever sits perpendicular to the record surface. Put a small mirror on the platter and set the cantilever down on it. Adjust azimuth so the cantilever and its reflection form a straight line. Then proceed as follows:

If you have the recent Hi-Fi News & Record Review test LP, which you should (Footnote 1), it includes a track with an out-of-phase, laterally cut test tone. You engage your mono button, or use a $Y adapter on your phono cables, and adjust azimuth as outlined below. Or use Bob Graham's little azimuth box, or make your own much less expensive device using a pair of cheap stereo interconnects. Cut through the wire on one channel only, strip some insulation from all four resulting ends, and reverse the leads so the "hot" connects to ground. Solder the connections if possible, and tape up the bare joints. If your arm's wiring is permanent, you'll need to get a pair of female/female RCA connectors (available at RadioShack) to go from your arm's male RCA leads to the cable you've just rewired. Otherwise, just substitute the rewired cable for your usual RCA phono interconnects.

If your preamp has a mono switch, engage it. If it doesn't, you'll need a double-female-to-single-male $Y adapter. Plug the rewired cable's male RCA plugs into the $Y adapter and the $Y adapter into one of your preamp's "phono in" jacks.

Now, play a mono record (very important!) and adjust the azimuth until you get the least amount of sound from the record. Ideally, you should get none, but usually there's some leakage. Some setup guys suggest you don't use a record with a great deal of high-frequency information or you might end up hearing the acoustic sound made by the stylus in the groove direct and get confused. I don't agree. I use a Mickey Katz Klezmerific record (oy gevalt!) or a mono Miles Davis album. I find having that high-frequency sound helps "null" the signal. Some folks argue that electrical "null''—or identical output from the two generators—is not necessarily the correct setting (again see Hansen's November 1996 letter).

In any case, the null point should be at or close to perpendicularity for most cartridges, and that's a good starting point—or ending point, depending on how tweaky you want to get. You'll have turned the volume way up to try to hear the residual crosstalk resulting from the null adjustment, so remember to turn down the volume before switching back to stereo or you'll blast yourself out of the room.

If you don't get a big, wide soundstage with a tightly focused center image smack-dab dead center, you may wish to make small changes to azimuth one way or the other—something accomplished more easily in some arm designs than in others, and impossible in some. If you hear no perceptible improvements by shifting in either direction, stick with the tried-and-true dead-on perpendicular setting.

Skating is a real, not imagined force resulting from the offset headshell angle. It causes the arm to drift inward, pressing the stylus against the inner groove wall. An arm with excessive lateral bearing friction will counter skating, but that's hardly the proper solution. While anti-skating—a counterforce—can never be applied with precision across the entire record surface, when optimized it is better than no anti-skating, in my opinion.

The HFN/RR record offers a variety of anti-skating adjustment tracks, none of which is as good as the one on the Omnidisc LP, which Telarc ought to re-press. (How about it, Jack Renner?) If you have the Telarc disc, follow the directions. Still, the HFN/RR tracks can help you get the job done. Do not use a blank space on a record, like the Cardas Sweep record, to balance the arm laterally so it doesn't move in or out when set down. That is a sure prescription for getting anti-skating adjusted wrong. It must be done under dynamic conditions—playing a modulated groove. When using the HFN/RR test record, remember: If the left channel distorts first, you need to apply less anti-skating. If the right channel distorts first, you need to apply more anti-skating. Both channels should start to distort at the same time.

Last but not least comes damping. Some arms provide a damping trough or cup, some don't. Before adding silicone or oil, use the HFN/RR resonance-point tracks to determine the horizontal and vertical resonance points of your arm/cartridge combination. Both should be about 5Hz above warp "wow" and about 20Hz below musical modulations. Ideally, both should fall in the 9–12Hz region. If not, apply damping until their effect is minimized. Even if they do fall in this region with no damping, you should try damping the arm—especially if it's a unipivot. The feel of a wobbly, undamped unipivot is extremely unpleasant; its sound can be, too.

If your setup sounds too bright at this point, try adding the recommended damping fluid a small amount at a time until the sound warms up. Too much damping and the sound becomes dull, slow, and lifeless, so go easy. But don't worry—you can always remove some damping fluid if you overdo it.

Wow, you're almost ready to play actual music. First, though, recheck your overhang and tracking force; hopefully, both will have remained where you first set them. If not, optimize them. If you're using a moving-coil cartridge, you might want to demagnetize it at this point using either the Cardas Sweep record or one of the electronic devices available. Put the stylus in the groove of a record to center the coil in the magnetic field before demagnetization. Don't allow the platter to rotate.

Finally, clean the stylus carefully. Never use a carbon-fiber stylus-cleaning brush with the arm locked in the armrest. If you do, over time you'll bend the cantilever upward and ruin the cartridge. Instead, unlock the arm so that the arm can "give" from any unwanted upward motion.

Now you're ready to enjoy that great analog sound! One final thing: If you're using a new cartridge, you'll probably have to redo some of these adjustments after 50 or so hours of break-in. Then you should be cruising down the vinyl highway in high style for a long, long time.

Footnote 1: Available from Acoustic Sounds: (800) 716-3553.