Analog Corner #5

(Originally published in Stereophile, November 12th, 1995)

Three news items before we begin this column:

First, I am sad to report the murder of Ed Tobin, who I once referred to as the "Yoda" of record plating. Tobin, a veteran of more than 40 years of record manufacturing, was responsible for lacquer plating at Greg Lee Plating in Gardena, California, and oversaw the production of stampers for AudioQuest, Mobile Fidelity, Classic Records, Acoustic Sounds, Reference Recordings, DCC, and many, many other audiophile and non-audiophile labels. Arrested and charged with the crime was Tobin's stepson.

Second: VPI's "Easy Analog" turntable/built-in phono section combo, to be produced in conjunction with Clearaudio and Gold Aero, and mentioned in my Hi-Fi '95 Show report last August (p.82), turned out to be not so easy: the project has been scrapped. Also on the VPI front: the company has delayed plans to manufacture its new pickup arm with a variety of upgradeable options which would have priced it between $900 and $2300. Due to the high demand for the $2300 loaded version, that's all the company plans to produce for now. [See VPI's letter in this issue's "Manufacturers' Comment."—Ed.]

Third: Owners of VPI TNT III turntables (which include the flywheel and outboard motor) who are using the Bright Star Big Rock TNT isolation base absolutely need to get Bright Star's new Mini Rock F base for the outboard motor. It replaces the VPI-supplied metal shelf and, as reported by Steven Stone in this issue's Follow-Up, results in almost complete motor isolation. The sonic improvements (ie, lower noise floor) are not subtle.

On with the Show: Mahler's 85-minute "Resurrection" Symphony is not exactly my idea of light summer listening, but that was the main course Seiji Ozawa and the BSO served up at Tanglewood on an early August Sunday afternoon. It was a press event, so I was there. When it comes to glomming all the free jumbo shrimp you can stuff down your gullet, I would've shown up to see Hootie and The Blowfish. (Well, maybe.)

The point of the TDK-sponsored event was to remind us to remind you that, thanks to a generous grant from TDK, kids under 12—up to four per parent or guardian—get free lawn tickets throughout the season. Truly a magnanimous corporate gesture, and very good PR.

Frankly, making a kid sit through an hour and a half of Mahler in the hot sun is prima-facie evidence of child abuse, in my opinion. (Thankfully, this particular Sunday was cool and overcast.) But not every concert is this heavy. Sometimes light classics are performed, like Berlioz's Requiem. Actually, "free" isn't always enough to get kids to classical music concerts. When I was a youngster you couldn't pay me to attend one—except maybe for the 1812 Overture, if there were cannons and fireworks.

The classical music world is perpetually bent out of shape because the audiences are so old. The worry is that pretty soon everyone will die off and there'll be no one left to attend. Hey, guess what? There'll always be new old people coming up to replace the ones that kick, so they should stop worrying! I should also remind you that part of the bill for Tanglewood is covered by an NEA grant, but, thanks to our "Revenge of the Nerds" Congress, that will soon end. One Piss Christ and a thousand classical music concerts get punished!

Anyway, the afternoon came complete with a shrimp-filled lunch at the Koussevitsky estate, Serinac (spells "Canires" backwards), overlooking the magnificent Berkshire Mountains; VIP parking a few feet from the gate; and tickets so close to the stage you had to wipe the musicians' perspiration from your face at the end of each movement.

This year our hosts really outdid themselves with the food—crab legs, pâtés, poached salmon, tenderloins of beef, Caesar salad, tortellini, of course all the jumbo shrimp you could eat, and fine California wines, including a Chardonnay which made the 85 minutes of Mahler bombast float by like a gossamer train wreck. Speaking of Mahler, did you know that Bruce Mahler—the guy with the parakeet on his shoulder on the Fridays television show back in the late '70s—is a direct descendant of old Gustav? But for the budgie, you can't tell them apart.

At lunch I overheard Hans Fantel and Julian Hirsch arguing over whether all symphony orchestras sounded alike. Fantel said yes. Hirsch said only if the conductors' batons measured the same length, diameter, and weight (only joshing).

The Mahler performance was spectacular, with the engorged BSO backed by the Tanglewood Festival Chorus—a grouping large enough to populate a small town—and soprano Barbara Bonney and mezzo Florence Quivar, both of whom spent most of their time on stage looking like Sally Jessy Raphael and Oprah Winfrey and not doing much vocalizing.

But the dramatic high point of the afternoon was the opening act: pianist Leon Fleisher made his two-handed debut after suffering 20 years with carpal tunnel syndrome in his right hand. His performance of Mozart's Piano Concerto No.12 in A was agile, had a good beat, and I enjoyed dancing to it. (Sorry, I don't do classical music reviewing, and with good reason.)

A letter-writer recently described my taste as "catholic." I do like classical music, and listen to a great deal of it. In fact, I own Haitink's Mahler 2 (Philips 802 884/885 LY), and am quite familiar with the piece. Masquerading as a philistine in audiophile circles is just too much fun.

The maine thing

I figured that as long as I was in Massachusetts, I might as well go the rest of the way to Maine and visit Rockport Technologies. But I wouldn't have made the eight-hour trek from Lenox, Mass. just to pay a social call on Andy Payor: he had something cool to show me—a scoop, really. I was to check out the first of three specially designed turntables Sony had commissioned Rockport to build—each, according to Payor, costing "more than a fully loaded Lexus."

Stung by criticism of its initial CD transfers of vintage, prerecording-tape–based catalog (ie, lacquers, acetates, and metal parts), Sony has committed to a complete overhaul of its analog transfer chain, and another go-around of its priceless heritage of American popular music, jazz, and classical. It wasn't just persnickety audiophiles (including yers truly) who were bitching. Everyone complained about the poor sound quality—including collectors of 78rpm originals. What they heard on Sony/Columbia's CDs was markedly inferior to the original 78s.

A deadly combination contributed to the poor sound: early digital converters; misuse of and primitive digital noise-reduction technology; complex, inferior-sounding electronics chains; and cheesy analog playback gear. Limburger-cheese cheesy, by audiophile standards.

Certainly it makes economic, moral, and cultural sense for Sony to do it all over and get it right. When the Japanese company bought Columbia records a while back, it was paying mostly for the back catalog—everything from Broooce to Bob to Duke. The preservation of the Ellington back catalog alone justifies the expense, and expensive it will be, with Cello contracted to provide the electronics and Rockport Technologies custom-building the air-bearing turntables.

Passing fancy

I love old technology: tubes, turntables, and automobiles. In fact, I drove to Maine in a 1972 Saab 96 I've owned since it was new—the original "jellybean" car that, back in '72, came standard with a "McGovern for President" bumper sticker and was driven by your longhaired English professor. Powered by a 65hp, 1700cc Ford V-4, the car didn't exactly set any speed records, though it had kicked serious butt on the rally circuit for many years.

My car, though, has a rebuilt engine (did it myself) fitted with oversized pistons, milled heads, an Iskendarian semi-racing cam, heavy-duty valve springs and dampers, and a two-barrel, high-performance Weber carb. It's one peppy sucker. Looks like Clark Kent, flies like Superman.

Anyway, there are guys on the road—for some reason, mostly balding mustachioed mid-'30s types wearing Vaurnets and driving white full-sized sedans like Pontiac Bonnevilles—who regard getting passed by my homely little bullet as the equivalent of a drive-by circumcision. They're happy at 60 until I pass them at 80. Then all of a sudden they have to go 90 to get ahead of me.

On this trip I watched guys literally risk death attempting to put their rear ends in my face. One guy on the Mass Pike tried using an exit lane to pass (on the right) the slowpoke in front of him. He almost had a head-on with a Cadillac entering the Pike on the same piece of road.

When the Road Warrior finally arrived at Payor's, I found the turntable in pieces. My job for the afternoon was to help assemble it so Andy and you and I could see what it looked like in one piece for the first time. Playing a record was out of the question—it needed a few days of wiring and other bits of final assembly, but I think the pictures speak volumes about the ingenuity of the design and outstanding build quality of what is probably the most expensive turntable ever built.

800 lbs of analog dynamite

Sony's needs were quite specific, and very different from those of the average analog-loving audiophile. For one thing, with three different-sized work parts, all three needing vacuum hold-down, the system required three interchangeable platters (10", 12", and 16" in diameter)—and the changeover had to be both rapid and foolproof.

Because actual platter speed was so variable in the early days of 78rpm (actually 78.26rpm) direct-to-disc recording, the new turntable had to be able to play at 78rpm ±10%, with dial-in, repeatable accuracy. Sony also specified half-speed playback of any of the 78rpm settings for half-speed mastering, as well as 33.333rpm (±10%) operation.

The drive system would be a massive, AC-hysteresis, synchronous motor turning at low rpm (300㪘), coupled to the inner platter via a nonelastic Kapton belt. This would be ground to a thickness of 0.002" to reduce belt-induced wow and flutter. A motor-pulley coverplate would protect the belt from fouling.

The motor itself has no permanent poles—they're printed magnetically on the rotor, which results in varying induction angles during startup. The design would allow the motor to easily synchronize a large inertial load.

In addition, the motor-pulley shaft would be fitted with two bronze sleeve bearings to carry the radial load, and a polished carbide thrust plate and ruby ball on top, the latter fabricated in Switzerland.

The motor would be dynamically balanced in two planes to rid the system of vibrations, and the entire assembly would be mounted on the plinth in its own high-mass damped subassembly and separate suspension system.

Quick, convenient phono-cartridge changeovers required a detachable headshell, as well as easily set and instantly repeatable vertical tracking angle, tracking downforce, and damping. Arching wires and airhoses—simply not acceptable in a work environment—needed to be hidden from view. In addition, Sony had one unique prerequisite: apparently the ceilings in the studios exude a particular precipitate that lands on the equipment. The air-bearing arm-rail would have to be protected against this fallout, as well as from greasy fingers and arms.

All of this meant that Rockport's Sirius 2 'table ($30,000) could serve as the launching point for the new design. (Indeed, Payor got the contract after demonstrating the Sirius to Sony's staff at its studios.) Nine months of computer-assisted design and production of assembly drawings lay ahead before the plans could be finalized and production commenced.

As with the Sirius, the plinth would be two thick slabs of machined and polished granite sandwiching a high-hysteresis polymer damping layer—only on a much grander scale.

The spindle bearing, as on the Sirius, would be a step-compensated air bearing with a high-pressure air-film providing both the radial (side load) and axial (thrust load) clearance. In other words, the whole thing floats, unlike other "air-bearing" 'tables, which use mechanical radial centering (ball or sleeve bearings) and provide an air film only for the thrust load. Rockport's bearings also apply a vacuum preload to set its "flying height" to within 200 micro-inches. With no contacting surfaces, the unit is essentially silent.

Unlike the Sirius, the Sony bearing would include an integral high-precision optical encoder to provide an exact count of the platter's rpm, which would be displayed on the control panel's digital readout (okay, the unit's not totally analog). Payor brought in Entec's Demian Martin to design the electronics.

The second-biggest problem Payor faced was fashioning the interchangeable platter system. On the Sirius and Capella 'tables, the platter is bolted directly onto the air spindle. For the Sony unit, Payor had to come up with a system which would provide the same degree of physical integrity, yet offer quick changeover.

What he devised was a two-piece platter: the lower section, machined from aluminum, would bolt to the air spindle. A large "O" ring, fitted into a channel on the platter housing, would provide a seal for the upper replaceable unit (urethane-coated, constrained-layer–damped, aluminum/acrylic composite) which would center easily on the platter housing via the hub assembly. With the upper unit so placed, a powerful vacuum would be created between the two sections (due to an air-evacuation channel built into the lower platter connected to the remote vacuum pump) which would suck the "O" ring below the contact point, creating a tight metal-to-metal fit.

The result, in effect, would be a single platter. Placing one of the upper removable platters onto the permanent lower one would also seal the air-evacuation channels for the record–hold-down vacuum system. For this platter design to work, the quality of the machining would have to be virtually perfect.

The tonearm, however, posed an even bigger engineering challenge, according to Payor. The main housing, machined from a massive, 40-lb solid block of aluminum, required precise three-dimensional modeling which would have been extremely difficult to do in the pre-computer era.

In place of the add-on damping trough in Payor's other tonearm designs, this one features a channel cut into the housing itself. Figuring out where and how all of the various compartments and moving parts (the VTA-adjustment block and machine drive, the cueing system, the bearing rail, the arm/counterweight assembly, and the damping-trough adjustment reservoir and control) would fit within the frame; and how the wires ("five 9s" copper conductors in a true Litz construction) and airhose would be hidden, and proper geometry maintained, required a great deal of ingenuity and mechanical design skill.

(Payor obviously has this stuff built into his genes: his father has custom-designed many mechanical and structural packaging systems for Pepperidge Farms for the past 30 years.)

As on the other Rockport turntables, the arm tube is an 8-ply, constrained-mode–damped, carbon-fiber/epoxy composite which provides high stiffness, low structural resonance, and low effective mass. Because of the removable headshell and the additional arm length necessary to copy with 16" lacquers, the arm tube on the Sony 'table has to be considerably more sturdy than the already stiff and inert ones used in other Rockport products.

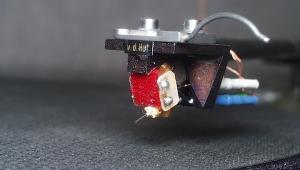

The removable headshell system uses electrically superior LEMO connectors, modified to fit within a custom-designed mechanical coupling, which mates the two pieces securely, forming a very rigid joint.

The entire shebang is supported with an active pneumatic, gimbaled-piston isolation unit, similar to but larger than the one used on the smaller Sirius, with a resonant frequency of 0.75Hz in both vertical and horizontal planes. This attenuates unwanted external vibrations at 12dB/octave above resonance. While the entire system floats, it is not bouncy.

To get the 500-lb plinth to float, and to provide air for the arm, platter, and vacuum system, requires an industrial-strength, piston-driven, oil-less compressor with an integral storage tank. Before reaching the tank, the compressed air circulates through an air dryer and filter, which lowers the dew point to –100ºF and ensures that no water vapor passes through the system. One of these remote-controlled air units is sufficient to run three turntables.

The would-be system

You will have noted in this column a large number of "would be" phrases. The reason is that none of what Payor proposed existed, except on paper. All of it would be custom-fabricated. When all the parts finally arrived at Rockport, Payor calculated that three machinists and more than 60, count 'em, 60 vendors had been involved in providing all the valves, switches, wires, gauges, metal work, printed circuit boards, electronics, air bearings, optical encoders, granite, milled and anodized aluminum, etc., needed to build the turntable.

Building the perfect beast

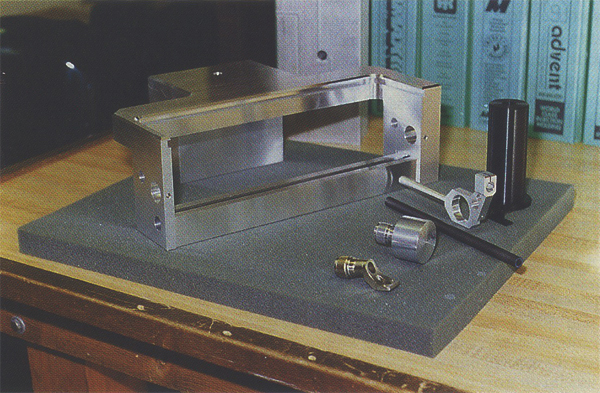

Would it all fit together and work as planned? When I arrived in Maine, it was time to put all the pieces together. Fig.1 shows some of the raw components of the tonearm: the large piece is the (upside-down) arm frame, milled from a solid block of aluminum. As shown, it rang like a xylophone. After being fitted with the other components pictured, it was essentially dead. The black tube at the top is the precision-threaded VTA adjustment pillar.

Next down in the photograph is the aluminum member which is bonded to the outside of the air bearing. The counterweight fits into the left-hand shaft, the thin black arm tube into the uppermost hole. The two other pieces are removable headshells: one in its partially milled state, one ready to use.

Fig.2 shows the granite plinth resting on the pneumatic feet built into the custom massive stand. The square cutout on the right is for the arm assembly. The center hole is the spindle-bearing housing. The cutout and hole on the left await the electronic speed-control chassis and motor assembly. Missing: the front plate containing all the analog pneumatic gauges and other control instrumentation, which fits into the space framed by the front feet and cross members.

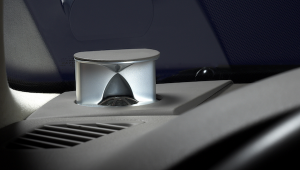

Fig.3 shows the electronic speed-control chassis and motor assembly in place. The black-anodized electronics panel with integral heatsink is fitted first, then the motor assembly is carefully lowered into place using the two handles. Note the heavy, constrained-layer–damped, stainless-steel mounting chassis. The entire motor unit rests on a four-point damped suspension. Protruding from the bottom left of the plinth, and obviously out of position, is a leveling sensor for the pneumatic suspension.

Fig.4 shows both the arm assembly and the platter air spindle in place. Note the large VTA adjustment knob on top, cueing lever and bar, polished stainless-steel bearing rail, and captured air-bearing sleeve assembly, and arm tube with detachable headshell. Fig.5 shows the subplatter with belt and large upper platter in place.

It's up! it's good!

As I write this, Andy Payor tells me that the turntable is hooked up and running as he envisioned it on the screen all those months and a thousand work-hours ago. How does it sound? Well, you should never take a manufacturer's word for the answer to that question!

By the way, if you're thinking, "Hey, I'd like to have one of these 'tables for my system," get in line. Payor says interested parties around the world want slightly modified versions and are ready to pay the staggering admission price. Each 'table will be custom-built. But first he has to assemble Sony's two other turntables. Besides, the holder of another enormous archive is interested, so for now don't hold your high-priced breath.

Meanwhile, Sony has poured the concrete floors in preparation for delivery of the first unit. By the time you read this, it should be installed and running. I hope to be there for the first demonstration. I told Payor that I hoped this would not be of some ancient shellac, but rather playback of some state-of-the-analog-art LP, like a Columbia "6-eye" pressing of Miles Davis's Kind of Blue, for example, or Bob Dylan's Columbia "360 Sound" pressing of Highway 61 Revisited, or maybe one of Classic Records' Columbia reissues. Give these guys a taste of what the old technology can do.

That accomplished, Sony's engineers can get about the business of archiving its prerecording-tape–era collection, secure in the knowledge that whatever's in the ancient grooves, the Rockport will probably retrieve it as faithfully as the art and science of analog record playback will allow. What happens when that signal reaches the A/D converter is another story.