Analog Corner #70

I also let them know, under "additional information," that this is current, not past technology. How so? This past February, Ying Tan's Groove Note Records produced one in Hollywood, and I was lucky enough to attend the session. And Chad Kassem's Analogue Productions has just recorded four D2Ds (see the April 2001 issue's Analog Corner").

Being a fan of this recording method (although not so enthusiastic about much of the music so recorded), I'd always wanted to observe a D2D session but had long since given up on ever getting the chance to do so. After all, who in 2001 would be stupid enough to try? Kassem and Tan, that's who!

Hooray for Hollywood?

So off to Hollywood I went for a weekend at Bernie's—Bernie Grundman's mastering facility, that is, where the session was to take place. Grundman has recently opened a new, spacious facility on Gower off of Sunset, down the block from CBS's L.A. news headquarters and close to some famous recording venues.

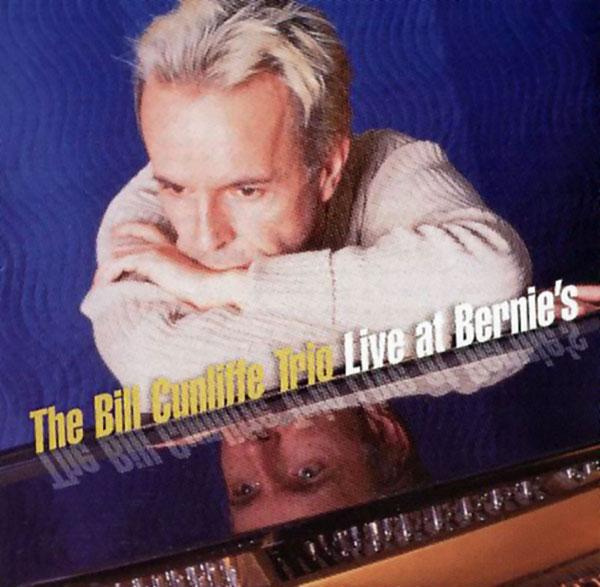

Weekend at Bernie's is the working title for Groove Note's D2D LP/CD/SACD release, which features the Bill Cunliffe trio. The 1989 winner of the $10,000 Thelonious Monk International Jazz Piano Award has quite an impressive résumé: he's played and toured with the Buddy Rich Big Band, Frank Sinatra, Natalie Cole, Joe Henderson, Freddie Hubbard, Art Farmer, James Moody, Bobby Watson, Ray Brown, and Joshua Redman, among others.

There was a strong Bill Evans influence in Cunliffe's playing throughout the weekend of D2D sessions, especially in the trio's interaction, but the pianist's flashy runs, high-energy chordings, stride interludes, and mix'n'match stylistic flourishes showcased an original player of incredibly versatility and creativity—one who, for all of his pyrotechnical abilities, never came across as a showoff. The guy's got more chops than a butcher.

Veteran drummer Joe LaBarbera was Bill Evans' final timekeeper; if I heard correctly, it was he who drove Evans to the hospital when his time was up. LaBarbera's playing was smooth, cool, and subtle, with soft, colorful touches set against the grain of the basic rhythms. He and Cunliffe were joined by the nimble Dutch bassist Darek Oleszkiewicz, and the telepathic musical interactions among the three made it obvious that they've been gigging together for a long time—no pickup session could yield this kind of lockstep communication.

But enough about the music for now—this is an audiophile column, after all. What I'm trying to say is that all of the time, expense, and trouble that went into capturing the group's music direct to disc was well worth the effort—something that can't be said about many D2Ds. For the record, my D2D faves, for music and sound, include: Bill Berry and his Ellington All Stars, For Duke (M&K/Realtime); Lew Tabackin, Trackin' (Japanese RCA, 45rpm); Great Guitars/Straight Tracks, with Charlie Byrd, Herb Ellis, and Barney Kessel (Concord Jazz); Michael Murray Playing the Great Organ in the Methuen Memorial Music Hall (Telarc); and a few from Sheffield Lab, including Michael Newman, Classical Guitarist and the sonically controversial Leinsdorf/LAPO series, which includes Stravinsky's Firebird Suite, Debussy's Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun, and excerpts from Prokofiev's Romeo and Juliet, all recorded with a single-point stereo microphone. "Too distant," was the complaint. Not if you were sitting in the balcony!

Setup

Would you want to be schlepping a fragile, heavy, temperamental cutting lathe to a recording studio or concert hall in 2001? Maybe the effort made sense in the pre-CD heyday of audiophile vinyl in the 1970s and '80s, but not now: the potential audience has shrunk. Even then, such dedication is slightly insane. Hats off to the guys who did it. Today, you bring the musicians to the lathe.

Veteran producer Joe Harley had never done a direct-to-disc recording, nor had he recorded in a post-production facility, so this was virgin territory for him. For Michael C. Ross, Harley's usual engineer, it was just another recording session, albeit in an unorthodox location. The duo's credits include many highly regarded sets for AudioQuest, Groove Note, and a variety of other labels, audiophile and otherwise, with the bi-coastal venues of choice being Ocean Way in Los Angeles and Bearsville in the Hudson Valley, about an hour and a half north of Manhattan.

At Grundman's, the "recording studio" was the large, irregularly shaped common space shared by the facility's various behind-closed-doors mastering suites. Fortunately, there was an easily isolated (physically and acoustically) area right outside Grundman's own corner room, which is where the two lathes are set up. Running mike cables and talk-back equipment from that space and through the door to the mastering room wasn't a problem.

Harley had procured one of the two Hamburg Steinway grand pianos in the L.A. area, and while piano moving is a given for a major-league recording studio, that's hardly the case in a mastering studio, where the music-makers are usually tapes and lacquers. Luckily, there was a large enough door to accommodate the piano. Joe LaBarbera's drum kit was set up fairly close to the piano in open space, and an isolation booth was built to prevent leakage to Oleszkiewicz's bass.

If you were thinking "two mikes" and into the cutting lathe, you don't understand how Harley and Ross work. Audiophile orthodoxy is not part of their recording game, and getting the sound to tape or disc is not a test of religious purity. They go for a certain result and use whatever it takes to get there. Natural sound is a goal, but they demand the upfront immediacy and dynamic excitement that only close miking seems to deliver. Harley's earset is based on the great jazz recordings of the 1950s and '60s, which may have been "pure" but were usually multi-miked. He's not looking for the somewhat distant, spacious sound preferred by Chesky, Water Lily, and some other labels.

Even if Harley and Ross could work in a natural acoustic venue like a church or concert hall, it's doubtful they'd use only two mikes—the sound they seek wouldn't be possible. Some audiophiles flinch at the idea of hearing a drum kit spread across the soundstage; certainly, if it's done in a super-exaggerated way, it can be distracting, even annoying. But as their extensive catalog demonstrates, the recording taste of Harley and Ross has always been at least good, and is usually exquisite.

There were six (count 'em) six spot mikes on LaBarbera's drum kit, plus a pair of vintage Russian LLomo 19a19s also on the drums, a pair of Sony C55ps on the bass, and a pair of AKG C-12A tube mikes on the piano. Actually, the AKGs were in the piano, which had been wrapped in moving blankets, its lid almost all the way down. The resulting sound from this magnificent instrument was awful from the outside, but what came through the monitors was fabulous. Two more mikes were set up to capture the room sound, but adding them to the mix caused the sound to become washed out and diffuse, so they weren't used.

The mike feeds were sent to a rented 1970s-era API 1602 mixing board placed at a right angle to Grundman's mastering console. The AKGs for the piano went first to an Avalon AD2022 preamp and AD2055 equalizer. There was also a touch of Lexicon reverb used on the piano to create some spaciousness. I can hear the purists ranting: "Of course there was no spaciousness—the piano was smothered in blankets!" Hey, I've heard air smother every instrument in some recordings produced using purist techniques. What counts is the end result.

Friday night, I accompanied Harley back to the studio for a final check of the setup. After all, there are no second chances in D2D recording. Cunliffe, Oleszkiewicz, and LaBarbera are busy, gigging musicians—there would be one long trio session to get what was needed, and that would be that. In fact, LaBarbera had a gig accompanying Toots Thielemans that Friday and Saturday evening at Avalon, a local L.A. club, so the session would have to end on time. LaBarbera's drum kit remained set up in the studio on Friday evening—he took only his cymbals to the gig.

Grundman's facility was eerily quiet when we entered. Setup man Mike Aarvold was making a few last-minute microphone adjustments, and everything seemed ready. But given the possible number of variables possible between musicians and equipment, especially in a recording session laid down direct to disc, you can never be sure what will happen when the tape rolls—er, the lathe spins. But Harley seemed confident.

In a small room near the front desk, the great tenor saxophonist Charles Lloyd—whose most recent album, The Water is Wide, was produced and recorded by Harley and Ross for ECM—was busy transferring his next album from PCM-1630 master to CD-R so he could listen to the just-mastered set at home. As reported in this column in January, though the The Water is Wide is labeled "DDD," the recording is actually AAD: analog multitrack mixed to two-track analog. The album deserves an AAA vinyl edition, and that may yet come to pass. Meeting Lloyd was a kick. He was as pleasant, gentle, hip, self-absorbed, and spacey as you'd expect and hope a veteran jazz giant would be.

The Session

It never rains in California? It rained every day I was there. I began the recording day with a delicious "heart attack on a plate" breakfast (Joe Harley's description) at the renowned coffee shop in my motel, The Best Western on Franklin Avenue. This was just down the block from Counterpoint, a used-book and -record store, where I'd found some decent vinyl the night I arrived—including a 45rpm promo single of Byrne/Eno's "Jezebel Spirit," which I'd been looking for since 1981. Good score!

When I walked into the coffee shop, I reexperienced one of the most annoying habits of some Los Angelenos: people sitting in booths facing the door immediately looked up to see if I was "somebody." When they realized I was "nobody," they gave me a disgusted look, as if to say, "What are you doing wasting my time?" Then they looked down dismissively, firing two negative shots across my bow in one smooth, smug move. Feh! Either that, or I'm paranoid. Or both.

The studio was buzzing when I arrived—thankfully, no one looked up. A veteran piano tuner had unwrapped the mummy and was busy fine-tuning by ear. (Don't try that at home.) At that moment, I was struck by the advantages of having an experienced producer. Harley knew the value of getting a really great piano for the session, knew who to rely on for the all-important tuning—in short, he'd assembled a team in which everyone was busy doing what they'd been hired to do, without conflict. Ross was double-checking the microphones and testing each channel, Grundman was going over the lathes (which would be turning at 45rpm), and a Sony technician was making sure the DSD recorder was ready to go. (You didn't think the SACD and CD were going to be sourced from the LP, did you?)

I thought back to the recording sessions for the Tron soundtrack I'd supervised at London's Royal Albert Hall back in 1982. I was a neophyte. We had more than 100 musicians on stage, an organist in the loft, and a remote crew from the BBC doing the recording—all of them waiting while the producer I'd hired duked it out with Wendy Carlos and her personal assistant over microphone placement. It was tricky, because the orchestration left holes in the music so Wendy could overdub synthesizer parts. The orchestra had to be miked just so to allow for the overdubs, but the engineer didn't want to budge from Standard Operating Procedure.

That 1982 dispute went on for some time, as the clock ticked and the dollars flowed. Eventually it was settled, but then another argument broke out between the producer and Wendy's assistant over who would get to look over the score during recording. The orchestra stood by, watching, as the two snarled at each other, each tugging at one end of a copy of the score. Such mirth. Fortunately for Ying Tan's budget and your listening pleasure, things went a bit more smoothly at the Cunliffe session.

One at a time, the musicians arrived, and the energy level in the room jumped. Bill Cunliffe is a small, puckish, high-energy guy whose spiky blond hair makes him look more like a punk rocker than a jazz musician. After greeting the people he knew and introducing himself to the few he didn't (including yours truly), he sat down to try the piano. A few chords later, he exclaimed, "Wow! I'm going to enjoy this. Incredible! What a great-sounding piano!" That was before the lid was lowered and the blankets reapplied. When that was done, I asked Cunliffe how he could possibly know what he was playing. He pointed to the headphones, which would feed back the mix to him. Cunliffe warmed up his fingers with improvisations and scales while LaBarbera made final adjustments to his kit and Oleszkiewicz made himself at home in his iso booth.

Inside the lathe room, Grundman, Ross, and Sony's DSD tech made their final preparations, while Harley looked on with label head Tan. It was Tan's money on the line. I don't know how much the session cost, but looking at the crew, the musicians, the piano, the room, Grundman, the lacquers, and figuring in the artwork and the pressing, it had to be pretty steep. What would come out of it all, if anything? With D2D, who knows?

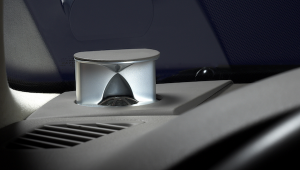

Finally, it was time for a test using both lathes, which were linked by a chromed metal bar to ensure identical cutting. One lathe was driven by solid-state electronics, one by the vintage vacuum-tube cutting amps used by Contemporary Records in the 1950s and '60s. Grundman slapped fresh lacquers on both, moved the cutting heads in place, lowered them onto the surface, and called out "10 seconds."

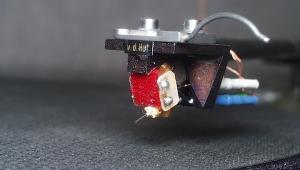

The talkback button on the API board wasn't working; Harley had to open the control-room door, call out "Five seconds," and quickly close it. After a short count-off the trio began, and the control room filled with music. In a few minutes the test was over, and the lacquers were played back directly from the lathe using 12" SME 3009 tonearms fitted with Shure V-15VxMR cartridges.

Of course, with all the phony L–R information, compression, and distortion added by the outdated, old-fashioned, mechanically primitive analog system, the playback sounded nothing like the mike feed. HAHAHA. Actually, the tube-driven cut sounded very close to the mike feed, but the solid-state lathe came up surprisingly short on the rich harmonic colors and dynamic nuances of the mike feed. Everyone heard it, so Grundman and Tan agreed to go with only the tube-driven lathe. Clearly, cutting the first wave of Classic's RCA Living Stereo reissues using solid-state electronics had been a mistake; the big improvements noted later by most consumers and reviewers was due in large part to the switch to tube-driven cutter heads.

Now it was time to get down to the real work. Remember: once cutting begins, there's no stopping until the end of the side is reached, 15 or 20 minutes later. The program must be carefully planned: Mistakes mean starting over, and between-tune time has to be tightly controlled. And there's no going over the time budget. Harley and Cunliffe planned the session around two song takes.

The first side went incredibly well. The performance was tight, the improvisations excellent, and the DSD playback showed the mix to be fine. After inspecting the grooves under a microscope, Grundman removed the lacquer, scribed the inner-groove information, and put the lacquer in a Styrofoam box for safekeeping. On to the next. Throughout the afternoon, the group played with incredible precision, with only a few clams resulting in ruined lacquers. Yet the feeling was never tentative or stilted. These guys, especially Cunliffe, let it all out, every take.

One performance, an extended take on "The Way You Look Tonight," was easily the highlight of the day and left everyone elated. Then came the bad news: Grundman had spotted "lift-off." That's where the cutting stylus actually lifts away from the lacquer and no groove is cut. Under the microscope, the tiny empty space looks like a country mile, but sometimes a careful, skilled plating engineer can actually "connect the grooves" with a special tool and the sonic results are seamless. And sometimes a good turntable/cartridge combo can actually play right through the lift-off inaudibly, even if the problem is unfixable. I thought the take had been so magical that Tan should just cut a lacquer from the DSD—but then, I didn't have a problem with the Clinton pardons.

Tan says he'll go ahead and plate that side and send out some test pressings to see if it's playable. I sure hope so. At the end of the day, Grundman had cut almost a dozen sides, most of which will be usable—enough for two multi-disc releases. Since what's usable and what's going to be issued on the first set weren't certain at the time of writing, I won't list the tunes here.

RTI's plating wizard, Gary Salstrom (footnote 1), attended the sessions; as soon as the final lacquer was put in the box, he took them off to RTI's Camarillo facility for an evening's worth of nickel baths—after attempting to fix the lift-offs. I can't wait for the test pressings, which I expect shortly. The final set should be available by the time you read this. If it comes out as I remember it, it should be spectacular.

On Sunday, Bill Cunliffe returned for another afternoon of smokin' solo sessions, recorded solely to DSD. He just loved that piano, and was eager to play. I hope his memorable version of John Lennon's "Imagine," replete with inventive improvisations and chordings, makes it to the SACD/CD.

I had a plane to catch, and had to leave in the middle of the second session. Akira Taguchi, JVC's XRCD executive producer, gave me a ride to the airport, as well as two XRCD test pressings of a new reissue of the fabulous Tony Bennett/Bill Evans Album. "Same master, different manufacturing process," he told me. "Different sound. One's much better than the other." Perfect sound forever.

SIDEBAR: In Heavy Rotation

1) Luna, Live, Arena Rock Recording Co. LPs (2)

2) Nancy Bryan, Neon Angel, 45rpm 180gm LPs (2)

3) Cannonball Adderley, In the Land of Hi-Fi, Speakers Corner 180gm LP (reissue)

4) Patricia Barber, Nightclub, Premonition 180gm LP

5) The Dandy Warhols, Thirteen Tales from Urban Bohemia, Schizophonic/Capitol LPs (2)

6) Gomez, Abandoned Shopping Trolley Hotline, Virgin UK LP

7) Teddy Wilson Trio, The Complete Verve Recordings, Mosaic 180gm LPs (8)

8) Ronu Majumdar/Ry Cooder/Jon Hassell, Hollow Bamboo, Water Lily Acoustics CD

9) Eliza Carthy, Angels & Cigarettes, Warner Bros. CD

10) Shirley Horn, You're My Thrill, Verve CD

Footnote 1: Gary's expertise was a significant factor behind the sonic success of Stereophile's 1997 Liszt Sonata LP. See "Cutting Up," Stereophile March 1997, where you will discover what is meant by "nickel bath" and other arcane terms to do with the magic of producing LPs from the master.—John Atkinson