Analog Corner #99

Press kits arrive at my house almost daily, trumpeting one thing or another, including upcoming hi-fi shows around the world. Recently, none has provided quite the jolt to my system as one sent by Steve Rowell of Audio Classics in Vestal, New York. It's for the New York High Fidelity Music Show, September 29–October 3. Don't worry, you haven't missed it. Well, you have—by 38 years. Rowell sent me a genuine classic: a press kit for a hi-fi show held in 1965.

The primitive-looking packet contained typewritten, stapled press releases, including: a backgrounder on the Institute of High Fidelity (IHF); a statement by the IHF's president, the late Walter O. Stanton (then also president of Pickering & Co.), entitled "Component High Fidelity Means More Than Better Sound"; a bio of Stanton; an exhibitor directory; a history of the component industry; a glossary of the then-new hi-fi lingo, "It Was Cross Talk, Not Back Talk: Chant of the Hi-Fi Buffs"; a roster of the seminar schedule; and, finally, the main press release, "High Fidelity 1965 Comes to New York." With a few minor changes, the last could have been the announcement for next spring's Home Entertainment 2004, to be held at the New York Hilton.

The 1965 show featured "the greatest exhibit of high fidelity component equipment ever assembled under one roof," the release announced. (So, I'm sure, will the press release for HE2004.) The 1965 event comprised 125 exhibits by 60 manufacturers spread over six floors of the High Fidelity Palace (the temporarily renamed New York Trade Show Building, at Eighth Avenue and 35th Street). Also in attendance were "major recording companies," which had cajoled recording stars to appear each night of the show, to meet attendees and sign autographs. The guest of honor on opening night was Metropolitan Opera and Capitol Records recording star Robert Merrill, from 7 to 8.

That late? Yes. You see, back then, hi-fi shows were timed for the convenience of people who actually worked for a living and who could afford hi-fi equipment. Show hours were 6–11pm on opening day, Wednesday, September 29, 1965; and 3–11pm Thursday and Friday, 11am–11pm (!) on Saturday, and 12–8pm Sunday. These days, daytime shows are more closely geared to the unemployed, based on the customer profiles supplied by retailers.

Did you know that there once was a special tax on high-fidelity equipment? According to the IHF press release, "Through a network of over two thousand high fidelity dealers throughout the country, an estimated quarter-of-a-million consumers were reached and asked to urge their congressmen to pass the bill eliminating the tax on high-fidelity components. The bill passed on June 22nd." The release also mentioned a successful show the previous March in Los Angeles, attended by "over 27,000 people."

There was even "home theater" back then as well. The show's main press release touted special exhibits featuring "two of the fastest moving developments in the industry—home video tape machines and automobile stereo equipment." Since Betamax video cassette recording was introduced in the late 1970s, I guess there could well have been an open-reel VCR format introduced back then (footnote 1), but I don't remember it, nor can I remember a television set equipped with video and audio output jacks.

The seminar panelists included Jack Birchfield, chief engineer for Electro-Voice; Abe Cohen, managing engineer of University Loudspeakers; Norman Eisenberg, audio editor of High Fidelity; Leonard Feldman, VP of engineering for Crestmark Electronics; Larry Klein, technical editor of Hi-Fi Stereo Review; and Ed Villchur, president of Acoustic Research. Blasts from the past for some of you, just names for the rest, I guess.

Exhibitors included: AcousTech; Acoustic Research, of 24 Thorndike St., Cambridge, Massachusetts (the address still brings tingles to audiophiles of a certain age); and Ampex, Audio Fan and Audio magazines, The R.T. Bozak Mfg. Co., Dynaco Inc., Elpa Marketing Industries (Cecil Watt Dust Bugs, anyone?), Empire Scientific, Fisher Radio Corp. (21-21 44th Dr., Long Island City), Harman/Kardon Inc. (still in Philadelphia), Hartley Products (Hohokus, New Jersey), IMF (Irving M. Fried), KLH Research and Development, Koss/Rek-O-Kut, J.B. Lansing, Marantz Company (25-14 Broadway, Long Island City), Pilot Radio, H.H. Scott (Maynard, Massachusetts), Shure Brothers, Tannoy (America) Ltd., and Viking (Minneapolis). Sony was there, as were Kenwood, Norelco, Pioneer, and Sharpe Instruments, but most of the manufacturers were American and most were located in the New York metropolitan area. The overseas buyouts had not yet begun.

According to Walter Stanton, a "fine" component system could be purchased for $250–$500, a "very fine" one for $500–$1000, though "one can spend up to $10,000 if he chooses." I'm no economist, but I'd bet adding zeros to those numbers would bring them up to 2003 dollars, which means hi-fi prices are about where they were in 1965, despite complaints from some quarters.

Even back then, according to Stanton, "High fidelity components are no longer just a means to develop the finest reproduction of recorded music, they have become aesthetic building blocks which enable one to express individuality and personality through his own component system." Those were repressed times. Today he would be able to cut through the crap to say, "Your hi-fi may help you get laid."

Except if it Involves Analog

The Consumer Electronics Association (CEA), which runs the annual Consumer Electronics Show (CES), among other things, is an umbrella group within the Electronic Industries Alliance (EIA). But judging by the CEA's exclusion of all things analog in its statistical research, EIA might as well stand for "Except if it Involves Analog."

Toward the end of July, I got an e-mail from the CEA's Communications division shouting about year-to-date sales of DVD-Audio and SACD players, which it says have "outdistanced all of 2002" sales of such players at a time when audio gear in general has seen a 12% decline. Is that surprising, given that most music-lovers under 25 probably listen through their computers? (I'm waiting for Sound & Vision's double-blind ABX test proving that "all computers sound alike.")

I called one of the consultants listed in the e-mail and asked her if the CEA tracked sales of DVD-A and SACD software. "No," she said. I told her that Stereophile's editor, John Atkinson, had recently told me that sales of new LPs in the first half of this years were almost three times greater than sales of SACDs, and that because most new-LP sales are not included in the SoundScan and other software-sales monitoring services, the actual LP sales figure is probably much higher. She didn't know that. I asked her for the numbers on new turntable sales. She went looking, though I was sure she wouldn't find them. She didn't.

Although the CEA apparently doesn't bother collecting such data, I surmise that sales of new turntables, cartridges, and phono preamplifiers are way up. I guess the old technology simply doesn't fit into the CEA's agenda, so the facts are best ignored.

ASR Basis Exclusive phono preamplifier

"Everybody's gotta get into the act!" Jimmy Durante used to say. That's what's happening with phono preamplifiers—they just keep being built, and I keep getting them for review. Up for evaluation in next month's column are new models from Perreaux, Musical Fidelity, Gram Slee, and a Chinese one, Ming Da. You can bet there'll be more.

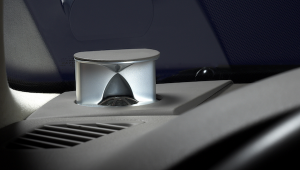

This month, I concentrate on one: from German designer Friedrich Sch;dafer, the unique and exceptionally fine-sounding ASR Basis Exclusive ($4950), built in Germany and imported by Fanfare International. This two-piece, battery-operated design is connected to the power supply via a large-diameter umbilical cord hardwired to the main section and terminated in a massive multi-pin connector. The battery supply—larger and heavier than the amplification and equalization section—is housed in a metal chassis with a thick acrylic front panel. The main unit consists of a single, unusually large double-sided circuit board in a plain-looking acrylic chassis that will win no points for industrial design—unless you like acrylic.

Unusually, the Exclusive is actually two complete, fully balanced stereo phono preamplifiers on a single chassis, entirely independent except for a shared, switchable output. You can have two turntables connected simultaneously, or have two tonearms on a single 'table (as I do), and easily switch between them. The fully balanced input stages feature both single-ended RCA and balanced XLR inputs, as does the shared output.

Each preamplifier is independently configurable via a series of DIP switches that control gain, capacitance, and resistance. An additional DIP switch acts as a "rumble filter" to allow you to limit low-frequency response to 2Hz or 20Hz. 10 more DIP switches allow loading to be adjusted from 5 ohms to 1k ohm for moving-coil (MC) cartridges; and, for moving-magnet (MM) types, 50k ohms in balanced mode and 36k ohms in unbalanced. There are switch positions for values of 5, 7, 10, 15, 22, 47, 64, 100, 220, 360, 470, 1k, and 50k ohms; other values are possible by choosing different combinations of switch positions.

Capacitance adjustment for MMs is more limited: 100pF or 320pF. A six-switch DIP-switch array offers gains of 0dB, +4dB, +8dB, +12dB, +18dB, +24dB, and +34dB. The quoted figure refers to additional gain above the preamp's MM gain; the Exclusive provides enormous amounts of gain for even the lowest-output MC cartridge, and +34dB gain by itself simply wouldn't be enough. The instruction manual's specifications page doesn't clarify things: it lists the Exclusive's maximum gain as "+32dB"! The manual, while informative and pretty comprehensive, needs some organization and a better translation.

The heart of the Basis Exclusive is a super-quiet Analog Devices microphone preamp based, believe it or not, on op-amps. According to the manual, after the adjustable linear gain stage, the signal passes through a passive low-pass RIAA filter and the low-frequency cutoff switch, followed by active RIAA equalization. The low-impedance unbalanced signal can then be output directly. An additional driver circuit is used for the balanced output signal. Only polypropylene and polystyrene capacitors are used in the signal path.

Battery charging is controlled by an optical digital logic circuit. A 72VA Philbert-Mantelschnitt transformer is used during charging but is automatically disconnected via relays during battery operation. There are six 6V, 12 amp-hour accumulators, and 400,000µF of buffering capacitance; when the voltage goes below 16.5V, switching is accomplished via a MOSFET-controlled circuit.

Charging begins automatically when the Exclusive is switched off. Fully charged, the battery can power the preamp for about 60 hours of continuous use. Should the batteries discharge, the Exclusive automatically switches to line voltage power and begins to recharge the batteries, if I interpret the poorly translated instructions correctly.

I'll spare you a complete description, but if you can follow the instructions, you'll know in great detail what is occurring with the charge circuitry at all times. At the push of a button on the back of the battery pack, a series of 10 LEDs lets you know the charge condition of the battery. You get about three hours of playback from an hour of charging. Basically, the charging and use of the battery system were transparent: during the entire time I used the Exclusive, I never ran out of battery juice. But if you leave it on accidentally for a few days, you probably will!

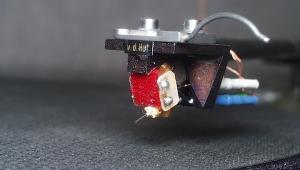

Connections, Configuring the DIP Switches, and Sound! For audiophiles with more than one turntable or with two tonearms mounted on a single 'table, instantly switchable dual phono sections is a major convenience. I had the Lyra Titan cartridge on the Graham 2.2 arm and the Transfiguration Temper W on the Immedia RPM2. A setting of +12dB of additional gain was more than sufficient for these MC cartridges, which are both of moderately low output. I preferred running the Titan at 1k ohm, but found the Temper W sounded best loaded down to 37 ohms, very close to the recommended 30 ohms. I left the Exclusive's rumble filter off, but made sure to mute the system before raising or lowering the arms. I ran the system single-ended at first, using Graham's excellent new IC-70 DIN-to-RCA phono cable on the 2.2, and Hovland Music Groove II on the Immedia arm. Harmonic Technology Magic interconnect ran to the preamp.

Once the ASR Basis Exclusive was configured, using it was simple: a single chrome rotary switch mounted on the front panel chooses between Off and either of the two phono sections, using either the battery or line power. I ran the Exclusive in battery mode at all times.

If you have a negative opinion of op-amps, listening to this phono preamp will change your mind. Whether it was the battery supply, the op-amps, the combination, or whatever, the ASR Basis Exclusive was easily the quietest phono preamp I have ever reviewed, with the exception of the $29,000 Boulder 2008 (which is equally quiet but is otherwise in a class of its own). Music didn't just emerge from the most jet-"black" backgrounds I've ever experienced with vinyl—it seemed to leap in stark relief from that silent backdrop. When I ran the Exclusive fully balanced (into the Halcro dm10 preamplifier) using Cardas Neutral Reference DIN-to-XLR and Shunyata Research balanced interconnect, the effect was only intensified. The Exclusive seemed to suppress surface noise to unusually low levels, making records I'd thought were noisy sound quiet, while allowing ultra-low-level detail to appear out of the vacuum-like blackness.

Cisco's upcoming reissue of Ian and Sylvia's stunning Northern Journey (Vanguard/Cisco VSD 79154) demonstrated the ASR's strong suits as well as its basic character. I bought the record in 1964, after Vanguard's black "Stereolab" label had given way to orange, and only recently have I found a really clean original. Cisco's reissue, mastered by Kevin Gray and Robert Pincus at AcousTech, beats the original in every way. It retains the original's sparkling brilliance, clarity, and overall acoustic honesty while adding levels of transparency, rhythmic snap, and microdynamic honesty the original lacked. Through the ASR Basis Exclusive the guitars, mandolin, and autoharp crackled with sparkling, transient-snapping excitement yet with plenty of body, while Ian's and Sylvia's voices had a you-are-there clarity and presence. Image definition was precise, three-dimensional, and well focused, while Russ Savakus' bass was taut, with plenty of wood behind the string plucks.

Against the Steelhead: Switching back to my reference Manley Steelhead phono preamp presented a completely different take on the same music: a more mellow overall balance, softer transients, and greater emphasis on midbass warmth. This made for a smoother balance that was easier to listen to yet still had plenty of detail—but it couldn't match the ASR's sheer excitement, or its ability to resolve the lowest-level detail in stark relief, all without sounding bright, etched, or hyper-detailed. Some listeners might prefer a bit more midband plushness, but a great deal can be accomplished by experimenting with cartridge loading. Still, I'm sure some will find the Exclusive's sound a bit too stark, perhaps too literal and a tad mechanical. I didn't.

I compared the Steelhead and the ASR with the classic Mercury Living Presence LP of Aaron Copland's Rodeo, El Salón México, and Danzón Cubano, recorded in 1957 (!) by Antal Dorati and the London Symphony (SR90172). I found the ASR's overall presentation in fully balanced mode airier, more transparent, deeper, wider, and more dynamic overall. The brass had a lifelike, piercing, yet plush realism that the more softly sprung Steelhead couldn't equal, and there was no match in the reproduction of the thwack of the timpani, which had far greater impact through the ASR.

It was an impressive presentation of a recording that, like many Mercurys, can sound thin and ungrounded. Perhaps my Steelhead is finally due for new tubes—because what the ASR did best in the mids, upper mids, and highs is what one usually expects from tubes! Yet some will prefer the Manley's lush, more mellow rendering compared to the brash, tightly sprung ASR's. Through both phono sections, when it got to the part of which composition copped by the Beef Council (or whatever the trade organization is called) for its television ads touting beef, my mouth watered.

I didn't see Bruce Springsteen in concert this summer, but I played much of his extraordinary-sounding Live in New York (Columbia C3 85490), cut from the high-resolution digital master and issued by Columbia on three LPs in 2001. The ASR's production of a 3D soundstage, with transparent yet solid images, small- and large-scale dynamics, and crystalline high frequencies produced an eerie likeness of being there that had me feeling the breezes of Giants Stadium. Switching to a Japanese pressing of Mel Tormé and the Meltones' Back in Town produced a totally different, far more laid-back sound, proving that the ASR could roll easily with the sonic punches without tripping over its own feet.

Conclusions: Its transparency, speed, and noticeable lack of midbass warmth mean that the ASR Basis Exclusive will not appeal to everyone or be appropriate for every system. But using the revealing Wilson Audio Specialties WATT/Puppy 7s, there was not a musical genre that didn't benefit from the ASR's strong suits: rhythmic snap; among the deepest, cleanest, most dynamic bass I've heard; and midrange and high-frequency transparency and clarity without etch, grain, or brightness. The ASR hung together rhythmically as well as any phono preamp I've heard. For $4950, you get two complete phono preamps, and you'll save money on expensive AC cables. (But if you think the battery will charge with better sound when using an expensive AC cord, you're nuts.)

Leaving aside the $29,000 Boulder 2008, which is in a class by itself, the ASR Basis Exclusive joins a handful of the finest phono preamplifiers I've heard. It's different from but on the same plateau as the Manley Steelhead and the Zanden 1000MC—and that's saying a great deal. While the Exclusive's fully balanced operation sounded best, its single-ended performance was not far behind.

A big, pleasant surprise, and a shock to my system. I absolutely loved the ASR Basis Exclusive.

Sidebar: In Heavy Rotation

1) Super Furry Animals, Phantom Power, XL Recordings CD

2) Bad Brains, Bad Brains' Greatest Riffs, Caroline CD

3) godspeed you black emperor, Yanqui U.X.O., Constellation LP (2)

4) The Incredible String Band, The Hangman's Beautiful Daughter, Sundazed 180gm LP

5) Kenny Dorham, Afro-Cuban, Classic 200gm mono Quiex SV-P LP

6) Sonny Clark, Cool Struttin', Classic 200gm Quiex SV-P LP (mono and stereo)

7) Gene Harris, The Gene Harris Trio Plus One, Groovenote 180gm 45rpm LP (2)

8) Aimee Mann, Lost in Space, Mobile Fidelity hybrid SACD

9) Mars Volta, de-loused in the comatorium, Universal CD

10) Dianne Reeves, A Little Moonlight, Blue Note CD

Footnote 1: That open-reel video recorder, made by Ampex, was featured on the cover of Issue 8 of what was then called The Stereophile. And believe it or not, while this magazine's then editor, J. Gordon Holt, wasn't able to attend the 1965 New York show, our long-time copy editor, Richard Lehnert, who was a youthful 15, did do so.—Ed.