Bobby Colomby Tells Us Exactly What Happened to Blood, Sweat & Tears, and Why This Groundbreaking Band’s Legacy on Vinyl Holds True to This Day

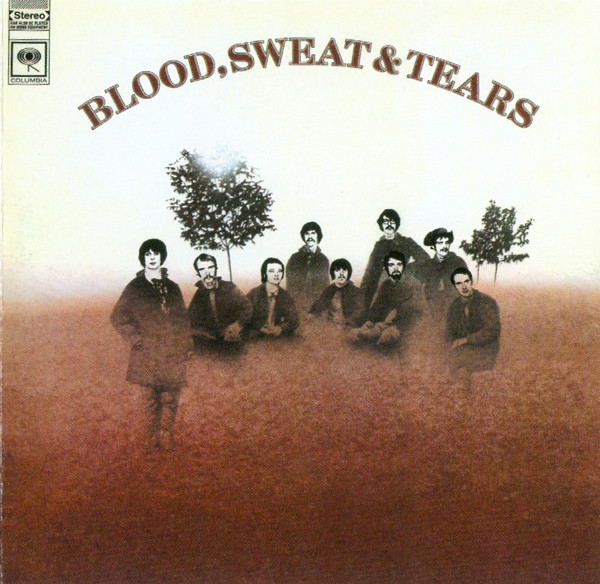

Blood, Sweat & Tears were on top of the world — and then, suddenly, they weren’t. For one thing, their second album, Blood, Sweat & Tears, had bested The Beatles’ seminal Abbey Road for the Album of the Year Grammy in 1970. Not only that, but the band was riding high into the new decade with a string of Top 5 hits like “Spinning Wheel,” “And When I Die,” and “You’ve Made Me So Very Happy” in their formidable nine-piece-band quiver when they embarked on a then-unprecedented Eastern European tour behind the Iron Curtain in June 1970.

What’s that, you say — you never heard about that tour? The reason why is fairly simple — well, sort of. “You couldn’t have found out, because we never said a word about it,” admits Blood, Sweat & Tears co-founding drummer Bobby Colomby. “We couldn’t.”

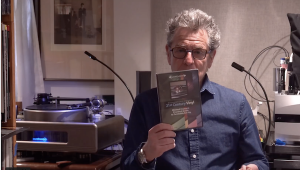

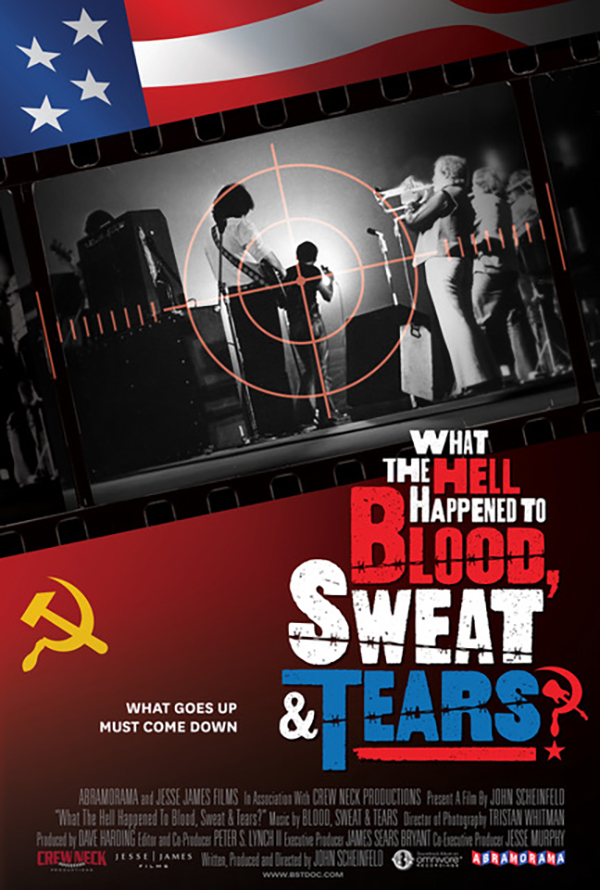

The broader reasons are vast, and, sadly, mainly political in nature — but the entire story can now be revealed in a gripping 110-minute documentary titled What the Hell Happened to Blood, Sweat & Tears? (Abramorama). The brainchild of writer/director John Scheinfeld — the man who helmed two of my personal favorite music documentaries, 2006’s The U.S. vs. John Lennon and 2010’s Who Is Harry Nilsson (And Why Is Everybody Talkin’ About Him)? — What the Hell Happened makes its nationwide debut in theaters across the country starting today, March 24. In fact, you can go here to see when and where this doc will be playing in a theater near you. (I’m also told a proper soundtrack will soon enough be forthcoming in both analog and digital formats.)

If anything, What the Hell Happened essentially vindicates BS&T as a versatile in-the-zeitgeist band that could play as good live as they were able to capture their special mojo in the studio — and, lest anyone forget, the nine-piece BS&T helped pioneer the deployment of a white-hot horn section in an expanded rock/pop context.

“This band, Blood, Sweat & Tears — we changed music,’ Colomby affirms. “We. Changed. Music. People would say, ‘Yeah, these guys can play.’ And there are people who really wanted to study us more. Bands weren’t confined to quartets of guitars, bass, and drums. All of a sudden, bands could do it like this, and do different kinds of music. We opened the door.”

Colomby, 78, and I got on Zoom together earlier this week to discuss the impetus for the documentary, the secrets contained within the runout grooves of certain records he produced, and his view of what the best-sounding Blood, Sweat & Tears track on vinyl is, and why. Ride a painted pony let the spinnin’ wheel spin. . .

Mike Mettler: I hope you don’t mind that I’m using the word vindicated after watching this riveting documentary. Is that okay by you?

Bobby Colomby: Well, yeah, a hundred percent. That is the right word. It is. I mean — and maybe it’s gonna sound a little lame, but I felt the band was great. In the documentary, David [Clayton-Thomas, BS&T’s then-vocalist/lyricist] is saying things like, “We were just musicians. We were just players.”

I grew up in a family with two much older brothers — Jules Colomby, and Harry Colomby. Jules started a record company [Signal (3)] and the first Music Minus One concept, but he was a jazz trumpet player — and a very good one, self-taught. And his dear friend was a guy named Miles Davis.

Mettler: We might have heard of him, yes.

Colomby: Miles would come by my mom’s apartment when I was growing up. And my other brother, Harry Colomby, managed Thelonious Monk for 14 years. So, the music I heard growing up was either the [Sergei] Prokofiev I fell in love with — but also jazz. That’s all I heard! I couldn’t understand why anyone would listen to anything else, because it was such great music.

I explain it to people like this. I say, “I grew up with Bach and Beethoven in my living room.” In a way, I always felt, like my brothers, that I was a jazz crusader. I just wanted other people my age to hear this music. So, the concept of the band Blood, Sweat & Tears having a couple decent, really good young jazz players, plus some decent folk-rock guys — two sets of my friends! (chuckles) — made sense to me. It was the guys I hung out with in Greenwich Village while I was in graduate school [at the City College of New York], and some really great, young jazz musicians.

When this thing started [in 1967] — Al [Kooper] was a mover and shaker. I knew nothing about any of the business thing [at that time]. I was just a musician who played jazz. But I didn’t hate rock & roll, and I didn’t hate pop music, which most jazz musicians hated. If you do anything outside of jazz, you were a sellout, you know? But I didn’t care. [Keyboardist/vocalist Al Kooper was a key creative force on BS&T’s debut album, February 1968’s Child Is Father to the Man. He left the band shortly thereafter, and Colomby and guitarist/vocalist Steve Katz found the aforementioned expat Canadian vocalist/lyricist David Clayton-Thomas to replace him.]

When you say vindication — for me, I thought this band really changed music. I thought it really affected people, every musician I knew. For years, and to this day, I have people saying, “Man, when I heard that, I got interested in this,” or “I picked up the instrument,” or “I played it seriously.”

Hearing all that — that’s all I would’ve wanted. People saying to me, “Oh, I heard of Miles. Oh, now I’m into Miles. Now I’m into the culture.” That’s it! For me, that was the win. The fact that the band was successful? Shocking. Shocking! No way I could have known that. I was studying to be an industrial psychologist, so I was in a completely different world.

Mettler: Interesting. So, what’s the psychology of why millions of people came to love Blood, Sweat & Tears music, doctor? What’s your theory?

Colomby: Well, I’m not officially a doctor, but I will treat you. (both laugh) No, I’m sorry.

Mettler: Oh, but I do appreciate that offer. I need help. You should see how many records I have here. (more laughter)

Colomby: I was gonna say, “Here’s some medication.” (more laughter) No, I’m kidding. In the old days, you would collect albums, you’d be in a room, and already, the shelves are filled, so now they’re on the floor. And then you start knowing people who give you more records, and then the albums start to creep towards you. And then they get higher and higher, and you’re surrounded by them.

Mettler: You’ve just described what’s happening in my living room right now. (both laugh) Seriously, though, from a psychology standpoint, why do you think so many people came to love Blood Sweat & Tears?

Colomby: Because we combined so many things. We had no limits to what we wanted to play — and, in a way, we were capable of doing it. I came into a band meeting after I became the bandleader [following Al Kooper’s departure] and I said, “Look, what I wanna do is, I wanna find music everyone here will like.” And they started laughing at me like, “That’s never gonna happen! We come from such various backgrounds musically. You’ll never find that.”

But [BS&T guitarist/vocalist] Steve Katz, who was my best friend at the time, he was playing music in his house like [French composer/pianist] Erik Satie, and I loved that! It was beautiful, so I bring into the band the idea of, “Okay, I’m gonna play some stuff. Erik Satie — anyone not like this?” And they’re going, “What are you talking about? That’s not fair, of course we do.” And then, of course, I’m also a big fan of Billie Holiday, so next it’s, “Okay, anyone not like [Billie Holiday’s 1942 classic] “God Bless the Child”? “Well, that’s not fair.” And I said, “No, that’s my point. I guess there is music everyone here likes — but the difference is, we can do it. We can play it.” And that’s the difference.

With that in mind, when you have songs that go from one end of the spectrum to blues, to Satie, to classical, to country — we covered so much territory. One of the things that hurt us, ironically, because we all like to feel like we own the music — “It’s us. We discovered it.” Back then, if you went in a taxi and they were playing something on the radio from my band, that cab driver would turn around and go, “Now there’s a band I like.” Or the parents of the kids would say, “Now there’s a band I like.” And we’d go, “What? Wait — this is my band.” You know?

But if you’re asking about the psychology of it — our potential demographic was gigantic. Gigantic! Like, when our version of “God Bless the Child” [from December 1968’s Blood, Sweat & Tears] was on R&B radio and going up the charts. We were not a marketing concept that was premeditated — it’s just what we did. I would love to say it was all carefully thought out, but that was hardly the case.

Mettler: Around that same time period, all of the guys in The Doors knew jazz very well, and they were doing their own version of, “We’re putting all these things into our music melting pot to create something that’s only called The Doors.” When you’re listening to the rhythms that [drummer] John Densmore was doing, and the things Ray [Manzarek] was doing on keyboards, you’re like, “What? Wait a minute. This is the broader scope of a deeper musical palette, not just AM radio fodder.”

Colomby: Whatever your core businesses in life is, we are all functions of a combination of our idols. It could be anything. We can point to these people who influenced us dramatically. But when you become successful, it’s because no matter how varied those interests are, ultimately, your personality and your character come through — and then you have a voice. That’s the case with The Doors. It’s the case with any unique band. I’m sure if you sat down with any of them, they would give you all these influences.

Mettler: I have done that with The Doors, and that’s exactly what they did. Well, let’s get into the importance of vinyl and how it relates to Blood, Sweat & Tears music. Because you had a nine-piece band to work with, were you cognizant of listening back to the mixes like, “How do we get all of these elements onto a record where we can get the production on it that we hear in our heads?”

Colomby: Oh, well, I produce records. I mean, that’s my fun. That’s what I enjoy doing. [Colomby has produced albums by artists like Jaco Pastorius, Chris Botti, and Paula Cole, to name just a few.] When I was 12 years old, I had a Viking 88 [reel-to-reel] tape recorder, and I had a razor blade and an editing block, I’m doing voices, and I have two little EV [Electro-Voice] mikes. Then I have this little jazz trio when I’m 15 or 16 — and I’m recording, and I’m editing. I’ve always loved that world.

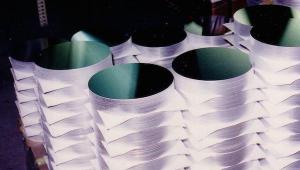

The only thing you have to be careful of on vinyl is, there is a limit to how much time you can have on each side. It’s about 20 minutes. I mean, there were jazz albums where there are songs that go the whole one side. But we were making pop music, in a sense, so the songs had to be around 3 minutes, around 3:54, and as you get closer to the middle of a record, the grooves get smaller — tighter. So the audio, the quality, is actually less.

Eventually, there was some consideration about what you put in the middle, because if it’s too loud or the song has too much groove element, the needle, the stylus, could actually pop right out of the groove.

Mettler: I bet when we were all younger and didn’t know much about any of the science behind it, if you ever cued up a record where the needled jumped out of it you’d go, “How could that even happen?”

Colomby: Well, since your audience is into this, I’ll go really inside-baseball for you. When you’re mastering, at the end of a side, you have the runout groove, right? Well, the lathe they cut the record on is also a bit of a microphone. So, you could go up to the lathe while you’re mastering, and when it gets to the runout groove, you could scream something in it — and you can hear it.

The fun of it was, when I was working on some projects, you’d get to the end of a song, you waited a second, and I’d go up to the lathe and scream, “F--- you, ahhhhh!” real loud.

And later, I would say to someone, “Oh, how’d you like the record?” “It was great.” I’d say, “Really?” “Yeah.” “Did you hear anything at the end of the side? What did you hear?” He’d go, “What do you mean?” I’d say, “Go up, and play it again. Turn the volume all the way up, and listen. And then you can hear a little f--- you aaaaah.” (both laugh)

Mettler: Can you give me the names of some specific records you produced where we can hear that happening?

Colomby: No, no! No. I can’t tell you — but I did ’em on more than a few, I’ll tell you that! (laughs heartily)

Mettler: Okay, well, if our readers come across any of them, I’m sure they’ll let us know.

Colomby: (laughs) Since you’re into the analog world, can I add some stuff you’ve probably already discussed a hundred times?

Mettler: Yes! Please do. I don’t want to assume everybody reading this knows everything about what you’re going to say, me included.

Colomby: Okay. I’m talking about analog recording now. When you record, there’s a thing called signal-to-noise ratio. What that means is, when you have your volume pod open without a note of music, and when you have it up because you’re recording something really soft, you have to increase your volume level, as you have tremendous amounts of noise. The noise comes from the tape itself. The board has all of these transformers everywhere, and each input has wires and all that, so there’s just a tremendous amount of noise.

If you are recording a band analog, and they play something like, (mouths softly) “quiet, quiet, quiet, quiet,” and then (yells), “Loud, loud, loud, loud,” (speaks softly again) “quiet, quiet, quiet,” you’ve gotta ride those things. If you just go for the, “Okay, let me hear how loud you’re gonna play it” and you leave it there, the soft part is gonna be really noisy.

Mettler: There’s a real dynamic range inherent in the music you guys made back then. We’ll hear something like a quiet vocal passage in certain Blood, Sweat & Tears songs where David [Clayton-Thomas] is singing fairly quietly, and then the horn section comes in full-force — and you don’t lose anything.

Colomby: You know why? Roy Halee, our engineer — and I will say this unabashedly — I’m saying he was 60 percent the reason why we were successful. 60 percent. As an album guy, if you listen to other albums on Warner Bros, on RCA, or on the other labels at the time and then you play a Blood, Sweat & Tears record, we were present, and louder, and cleaner.

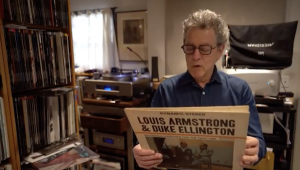

They used that record, our second album [the aforementioned Blood, Sweat & Tears], in every stereo store. That’s how they sold their equipment. And they sold probably another 100,000 albums for us, just because of that.

Mettler: Right, just like how those Simon & Garfunkel records Roy worked on around the same time as yours are still great to listen to today. It’s almost unbelievable how good they hold up.

Colomby: Unbelievable! You’re right. So, Roy would ride the faders. Why? He was learning. He would never do anything in one take. He’d say, “No, no, no — not yet. Let’s keep going.” Because he wanted to learn the song well enough so he could ride it. When it was loud, he would lower the fade, and he’d also take care of the soft. There weren’t just limiters everywhere. What a brilliant engineer this guy was, geez!

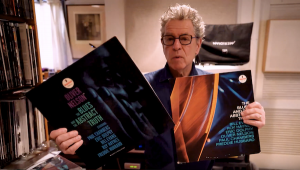

Mettler: If we want people to cue up something from that second Blood, Sweat & Tears album to check this out, what do you consider to be the best audition track for our audience? Like, “Go put the Blood Sweat & Tears vinyl on, and play this track”?

Colomby: Yeah, that’s a good question. I think the best “audio” song may be the song that has the most space, which is “Spinning Wheel.” It’s extremely defined, there’s room between the grooves, and everyone isn’t playing over everything else all the time. “More and More” is exciting — but it’s just wall-to-wall playing, so “Spinning Wheel” is probably the best “audio” track on that album, you know?

I think our second album, which was a good-sounding record, was the first record where drums were recorded in stereo. If you look at the full dynamic range of drums from cymbals to the bass drum, sonically, drums cover a lot of territory. Having drums be in stereo was so new at the time. If you had a good stereo system, and you could hear a hi-hat over there, and a floor tom over there — it was fun. It was fun to do.

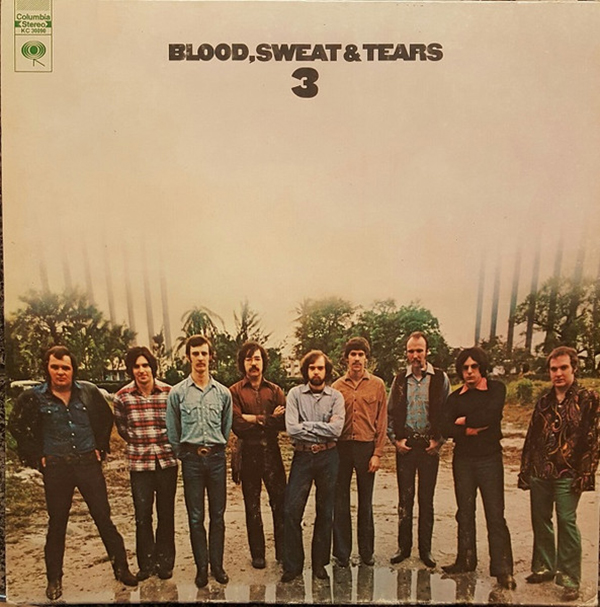

Now, on the third album, which I also did with Roy [June 1970’s Blood, Sweat & Tears 3], that was one of the best-sounding records I’ve ever heard in my life. But CBS Records — Columbia Records — was in such a hurry to put that record out because it was so long overdue, and people were excited about hearing the next record.

There is a point when you’re printing vinyl from the masters and from the mother tapes — that whole process — and there’s a limit, because they wear the stamper out. But they were in such a hurry that they let the stamper go way past its due date, basically, and some of the records didn’t sound that great. I mean, it sounded great once you got into it — got into the music — but the volume and the definition and the discrete tones just weren’t there.

I remember hearing the record when it came out and I went, “Oh my God, what’s wrong?” I had a tape of it that’s unbelievable sounding. It’s really an amazing sounding record. But the vinyl version — if you got lucky, you got an early pressing, but they pressed millions of them immediately.

Mettler: Knowing all of this now, can we lobby for proper analog remastering for the early portion of the Blood, Sweat & Tears catalog — the first four albums?

Colomby: Well, we’re lucky to even get royalties from these labels. I wouldn’t even know who to ask. I was an executive at Sony for many years — but, seriously, I wouldn’t even know who to call!

Mettler: Hopefully, we can get some interest in that idea from the powers that be, now that the documentary is out and we know how good the band sounded not only in the studio, but also on the live stage.

Well, you probably have to go do 50 other things, so let me wrap things up with this. Let’s jump ahead 50 years from now. It’s 2073, and unless science does weird stuff, Bobby, you and I are not physically on the planet then, but —

Colomby: (interjects) Why do you have to remind me of my daily nightmare? (laughs)

Mettler: (laughs) We’re all with you there! Anyway, however people listen to music in the future in 2073, and they type in “Blood, Sweat & Tears,” what do you want them to get out of that listening experience?

Colomby: The feeling that we discussed about what the end result of this film should be. I want them to say, “This was a really great band. They were ahead of their time, and they made a difference — and they made me want to hear other types of music.” That’s it. I’m not concerned with, “Gee, the guy, that drummer, he sure has a good left hand,” or — no. It’s a totality.

In my own little stupid way, I wanted to raise the bar and just get people to play better, and to have a singer whose lyrics you understood, and people playing in tune. Honestly, if something’s outta tune, it physically bothers the crap outta me!

It was all just fun — and there were some wonderful musicians in that band. Seriously.