Immedia RPM-2 tonearm Page 4

But the great records—the wideband, dynamic ones, the ones that brilliantly balance direct and reverberant sound, that get instrumental and vocal timbres correct, that place believable images in three-dimensional space, that demonstrate engineering genius—the records made by the Roy Halees, Glyn Johnses, Bill Porters, Geoff Emericks, Henry Lewys, and Ron Malos of the pop world; the Fred Plauts, Harold Holzers, and Rudy Van Gelders of the jazz world; and the Bob Fines and Lewis Laytons of the classical world—well, those were well served by the RPM-2.

Does that mean that I think the RPM-2 is the "best arm in the world"? Sorry, I'm not into that kind of phony, fawning hyperbole. Given the high quality of the competition and the wide variety of valid sonic tastes audiophiles exhibit, I'm repelled when I read any review that indulges in such egomaniacal crap. Nor am I into providing the gullible with easy answers and cheap, sycophantic thrills. You want that? You know where to look.

No doubt some audiophiles will prefer the lush, sweet midrange of the JMW Memorial arm, or the upper-octave airiness, roundness, and overall graceful balance of the Graham. Then there's the Wheaton, which I'll review next, and the world's other great arms—like the Naim ARO (though that does have some serious ergonomic limitations, as WP reported in his review in May '96). As for the Rockport 6000, it offers another set of sonic pleasures in terms of air, textural subtleties in the very upper and lower frequencies that the RPM-2 may slightly exaggerate or harden, plus a complete freedom from "mechanicalism," probably owing to the Rockport's tight air bearing and linear track across the record. But it simply can't match the RPM-2's bass performance at this point (nor can any other arm I've heard).

Thoughts

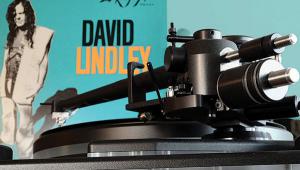

What accounts for the RPM-2's solid, superb performance? Clearly Allen Perkins (also a fine drummer; not surprising, given his arm's timekeeping abilities) has done his homework and designed an arm with some unique and ingenious engineering features that, in some ways, give it a mechanical advantage over its competition.

Is it the bearing pivot point, which remains at stylus height regardless of VTA changes, that accounts for the RPM-2's superb performance? Or the bearing's rigidity and intimate mechanical "ground"? Or the rigidity and mechanical integrity of the arm/turntable interface? Perhaps.

Is it the purity of the electrical path—a single wire from headshell pins to RCA plugs, instead of the series of connectors some other arms feature? Perhaps.

Is it the large-radius damping surface, greater than that of any other arm? Perhaps. The complex "decoupled" counterweight mechanism? There, probably no. The RPM-2's counterweight is no more "decoupled" from the arm's mass than the Graham's or VPI's.

Perhaps some of the RPM-2's sonic clarity and focus is attributable to the exquisitely machined, constrained-layer-damped TNT armboard Immedia supplied with the arm, and which the company plans to offer TNT owners for around $400. The board is much heavier and far more mechanically inert (tap it and you'll feel and hear) than the solid slab of acrylic VPI gives you.

Whatever the reasons for its superior performance, the RPM-2 is in the top echelon of tonearms.

Conclusion

While the RPM-2 is, for now, my favorite-sounding tonearm, it is certainly not for everyone, either sonically or physically. Consider that, if your turntable plinth is anything less than superbly isolated from its motor and/or the outside world, the arm's mechanical grounding is a two-way street—vibrations can travel into the bearing as easily as out. In addition, if you need to make quick cartridge changes—say, to play 78s or less-than-pristine LPs, or if playing old 45s with a $3000 transducer is not your thing—you might be better off with the ergonomically superior Graham, which allows you to change armwands in seconds.

If you like playing around with tonearm wire, the RPM-2 isn't for you—you have no choice there, nor can you move the 'table beyond the 3' reach of its interconnect. And forget about changing VTA during play. Remember, when you change VTA with the RPM-2, you change both VTF and damping. So while the RPM-2 offers complete adjustability, it is not the arm for the audiophile who regularly likes to "play" with his tonearm—unless you enjoy wielding a syringe!

Finally, the instruction manual is simply inadequate if you plan on setting up the arm yourself. Like most computer manuals, it makes gigantic leaps from point to point, into which all but the most experienced analog person will fall during setup. Yes, I'm grasping at negative straws to blow dirt on this product. It is, in most ways, brilliantly designed and executed, and it sounds bitchin'! The Immedia RPM-2 demands a serious audition before you choose what may be your last tonearm.

- Log in or register to post comments