Jack Pfeiffer Interview Part 2

M.F.:Now that whole "Dynagroove" thing. Do you want to....

J.P.:Well, I'll dispose of it quickly. Some of them were great, great recordings too.

M.F.:Recordings yes, but....

J.P.:Yeah.

M.F.:Once they got on to disc though....

J.P.:Well.

M.F.:The difference was in the cutting, correct? It wasn't in anything else.

J.P.:It was in two places, basically. It was in the cutting, but it was also in the mix down, because the head of our engineering department came up with a device to make the translation from a high level of listening to a moderate level of listening that most people listen to. And to make that translation from listening to it at high level to low level or lower level, it changed the whole ear characteristic change.

M.F.:The Fletcher/Munson curve? ( Named for the researchers who demonstrated that at lower sound levels the ear/brain loses low frequency sensitivity in a predictable fashion. Thus some electronics feature a bass boosting "loudness" control).

J.P.:Yeah, that's right, and he designed a device that was a compensator that varied with the level of the music.

M.F.:Varied frequency balance?

J.P.:Yes, that's right, it varied the frequency balance with the level of the music. Now what his biggest mistake was, he called it a "dynamic equalizer", and every critic came out and said, "Oh, but they've equalized the dynamics," and, of course, if you listened, we didn't.

M.F.:It equalized the frequency response based upon the dynamics.

J.P.:Yes, but just calling it a dynamic equalizer was a big flaw.

M.F.:Yeah.

J.P.:I had a lot of confidence in the system, in fact I worked with the engineers both in Princeton and in New York, and I supervised every Red Seal recording session, whether I was producing it or not.

M.F.:But why not leave well enough alone? That's what I could never understand.

J.P.:Well, we had a lot of pressure at that time.

M.F.:People complained? Were people complaining that it was too dynamic?

J.P.:No people were complaining that our records were too soft overall. Because we were trying to put the complete dynamic level, and in order to get that level we had to lower the overall level.

M.F.:So they were saying when it got down to the lower levels you couldn't hear it?

J.P.:Well, it would be under the surface noise.

M.F.: Okay.

J.P.:And there were other companies, there was a company called Command .....

M.F.:Oh, I remember

J.P.:You remember Command?

M.F.:Sure Enoch Light's label.

J.P.:Yeah, and he was doing 35 millimeter.

M.F.:And Bob Fine was doing some of those.

J.P.:And he put out some really powerful records, and our quality guide George Marek said, "We've got to compete with that, so go do what you have to do." So I got together with our Engineering Department, and I got together with our lab at Princeton, and we came up with it. I said I would supervise all the recording sessions and try to limit the number of microphones and try to keep this as simple as possible so that we get the best possible recording, but we've got to make sure that we get it on the record right, and we've got to make sure that our mix down reflects some of the thinking about this translation from high level playback to low-level listing.

M.F.:Right.

J.P.:And so it was an integrated program between all of us to create, and again, our publicity department came up with this idiotic name "Dynagroove"

M.F.:They lucked out with "Living Stereo" and then they messed up with "Dynagroove". Well it happens.

J.P.:Well the pressings were not good for one thing.

M.F.:Yeah.

J.P.:Which totally acted against the whole program because all of the technical aspects leading up to the pressings were very carefully organized.

M.F.:Now does this mean if some of these "Dynagroove" recordings are gonna come out again on vinyl does that mean that the tapes have this encoded on them?

J.P.:They go back to the original tapes, there's nothing encoded there. The Dynamic equalizer was only used in the mix down.

M.F.:So, in other words, these could be restored, I hate to use that word, but ....

J.P.:And there is some interest now in coming out with a "Dynagroove" series.

M.F.:And call it that?

J.P.:Yeah.

M.F.:Really?

J.P.:Um hum.

M.F.:On CD or on vinyl?

J.P.:Well, on CDs, at least from our people. We've gotten some feedback from our Europeans mostly. Strangely enough, when they got the "Dynagroove" product originally, you see, they they couldn't cut the records the way we were cutting them, because they didn't have a device that was devised at Princeton to limit the distortion at the inside of the record. It was an anti-distortion device.

M.F.:Well what did it do to limit the distortion?

J.P.:Well, they had what they called a complimentary distortion or something like that.

M.F.:So they figured out what kind of distortion the average turntable was gonna be and.....

J.P.:That's right. You see, at that time, primarily it was a spherical diamond stylus.

M.F.:Yeah.

J.P.:And the cutting stylus was an ellipse, and to make the translation from elliptical to a sphere, our engineering minds in Princeton said, "You have to put in some kind of distortion there in order to change the space of the groove so that the sphere can track it properly on the inside."

M.F.:I see.

J.P.:And that was incorporated in Dynagroove too?

M.F.:That was added in the cutting process?

J.P.:That was in the cutting process, and when we listened to lacquers, I must say, they were really very effective. And even some of the pressings that came out were very effective too. I remember I got a letter from Avery Fisher, of all people, who said, "You have done the most glorious thing that I can think of. These are the greatest recordings I've ever heard." Well, we've done something right.

M.F.:Yeah, but....

J.P.:But the general critical response was based primarily on that idiotic name of that dynamic equalizer. We had a press conference and we explained it all to them and tried to show them everything that we had done, as honestly as we could, and yet even after explaining this dynamic equalizer,-just having that name....

M.F.: But....

J.P.:And they said, "Oh, well they've squashed all the dynamics," and, of course, we didn't, but that's what they thought.

M.F.:Yet most audiophiles still think that when it went to "Dynagroove" the sound just wasn't very good.

J.P.:I know. I think a lot of it had to do with a combination of the pressing and this distortion that they added toward the end of the record. It changed things a bit, because every sphere wouldn't be the same.

M.F.:Well, not only that, let's just say you're playing it on a micro ridge or even an elliptical stylus cartridge. today!

J.P.:Yes, if you're playing it on a spherical cartridge.

M.F.:Maybe it's better, but today you're playing it on these very wide elliptical and micro re-cartridge.

J.P.:True.

M.F.:So you're gonna have that distortion in there cause it's not gonna be compensated out.

J.P.:That's right.

M.F.:That's what the problem is today.

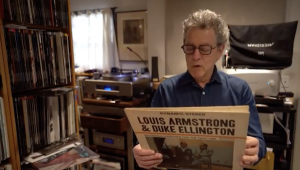

J.P.:But the original recordings were really, really very good. A lot of them were Boston and Leinsdorf.

M.F.:I have some of those "Dynagooves" and those do sound good, no matter what anyone says.

J.P.:Yeah.

M.F.:There was an interim period where it was the red label with the dog on it, and it still said "Living Stereo" and "Dynagroove". They sort of slowly crept away from one toward the other. You know, I bet there probably are people who will swear that early "shaded dog" "Living Stereo" "Dynagroove" records sounds better just because they have those earlier logos!

J.P.:[Laughs]

M.F.:In their heads right?

J.P.:Yeah. I think so, yeah. Well, too, much of sound is a matter of taste, you know, a matter of experience and what you get used to listening to, and I don't know. I think a lot of people still prefer a lot of the older pressings because it had the warmth to it, you know, and they say you hear all that room sound.

M.F.:The lack of bloom is a big complaint I hear.

J.P.:Well...

M.F.:And that's what you hear in the concert hall also they say, but I go to concert halls and it gets pretty rough in there sometimes- even Carnegie.

J.P.:Orchestra Hall in Chicago was the worst listening environment I was ever in. I used to hate going to concerts there.

M.F.:Yeah?

J.P.:But, of course, when it was empty it was totally different.

M.F.:And some of those are great recordings.

J.P.:Those are amazing recordings.

M.F.:Yup, and the tapes have held up over the years which is a good thing also.

J.P.:Yeah, I just keep my fingers crossed that we can preserve it.

M.F.:Are you going to re-transfer the whole thing over again 20 or 24 bit 96K sampled-or whatever gets chosen-when DVD happens?

J.P.:Yeah [laugher]. You know, we're going through a problem now transferring all of our vault from Indianapolis to a preservation area in Pennsylvania. It's an abandoned mine, and it has been converted into a total humidity and temperature controlled environment. And for the first time all of our assets will be there.

M.F.:Oh.

J.P.:Not only BMG but Arista and all of the other BMG companies will be in there.

M.F.:Uh, huh.

J.P.:Except for the European ones. This is going to be our North American vault.

M.F.:Are field trips available for stories?

J.P.:Oh probably.

M.F.:I would really like to do that.

J.P.:Yeah. Well they're in the process now of moving it. Of course, it's total chaos.

M.F.:Oh, I can imagine.

J.P.:It's just total chaos. They have moved most of metal parts I think, and most of the pressings from the old 78 days, but the tapes are in the process of being moved now, and we're still trying to do production, you know, sometimes we order tapes, well they're not here and they're not there. Is there somewhere in between?

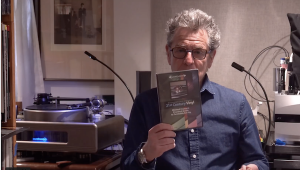

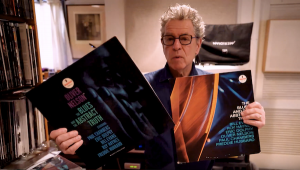

M.F.:I got to tell you the truth. I'm not happy with a lot of the jazz CD transfers of things that they're doing. Not at all.

J.P.:Really?

M.F.:Yeah.

J.P.:I don't listen to them anymore.

M.F.:Because they're doing digital "restoration", you know, a lot of "cleaning up" and revisions.

J.P.:Oh really.

M.F.:They just don't sound that good. A lot of the jazz ones have been very disappointing to me.

J.P.:Really?

M.F.:I mean Our Man in Jazz by Sonny Rollins in particular.

J.P.:Yeah.

M.F.:It's a classic. Well they're gonna do it on vinyl at least.

J.P.:Are they? Oh wonderful.

M.F.:And it's an amazing recording. It is. You're there at the Village Gate.

J.P.:Sure.

M.F.:And BMG did a CD where they "restore" it. The original engineer went back in and put it in sonic solution or something, and I think remixed it, and it's dead sounding. You know, they should, and it's very annoying, they should just, it is what it is, and they should let it be.

J.P.:Let it be, yes.

M.F.:Exactly.

J.P.:I know, I was talking to Tony Hawkins at breakfast and I said I went to Germany because we have an arrangement with Melodia now, and they're gonna do the transfers and all the processing in Berlin-over my dead body-but that's another story [laughter]. I wanted to do it because I thought we have the most experience in restoration in our studios in New York.

M.F.:And you're using the UV22 (A/D converter)?

J.P.:Yeah. Yes, but from a commercial point of view and then in a financial way, it didn't seem right (to ship everything to New York) so we had this company in Berlin which did do a lot of the Melodia transfers for Eurodisk for a while....

M.F.:Right

J.P.:They gave the contract to them to do all this transfer work, but I said, "Look, let me see what they've got and what they're doing," and I went over, and they've got everything. I mean they've got Sonic Solutions, and they had An Apogee UV22, and they've got everything. And they've got bit mapping, noise shaping....

M.F.:How you use that stuff is what counts.

J.P.:That was the whole point, I said, "Gentlemen, you know, it's nice to have all these play things, but this is what counts."

M.F.:Exactly.

J.P.:And use your judgment, please use judgment about what you incorporate into this, because you can make some terrible mistakes, and they have, unfortunately.

M.F.:If people don't want to hear hiss, let them go to hell.

J.P.: [laughter.] But they wouldn't be buying these older recording if they didn't realize there was some hiss involved.

M.F.:That's right.

J.P.:I mean when you buy a 1936 recording of Richter you don't care whether there's a little noise there.

M.F.:Right. Unfortunately, when they get rid of the noise, you get rid of some of the performance.

J.P.:Of course.

M.F.:That's the whole feel of the performance.

J.P.:That's right. The excitement of sound is a part of the performance, and they don't realize that. So I made a deal with them. I said, "When you get the tapes from Russia, you send me a DAT, and I want to hear what you're getting, and then you send me your master, and I'll compare them and see what you're doing."

M.F.:Well then I think we'll be in better shape with those.

J.P.:Well, it's just to let them know I'm leaning over their shoulders, and still, they've been doing terrible things. They've been using the No Noise™ excessively, and I've been complaining about it and "Well, it's because they don't get the right tapes from Russia", they say. I think that that in fact is part of the problem, because some of the Richter tapes have been showing up with synthetic stereo added to it.

M.F.:Oh great. That's always fun.

J.P.:And they're supposed to be giving us original tapes from Russia, and I said "They're not," and, of course, Russia says "Well, unfortunately the original tape wasn't available, so we had to give you the best possible." I don't know.

M.F.:Well.

J.P.:They grab something and they transfer it. Too bad. You can't be everywhere, you know.

M.F.:No, of course not.