"Living Stereo" Legend Jack Pfeiffer's Last Interview Part 1

Jack Pfeiffer: The Last Interview

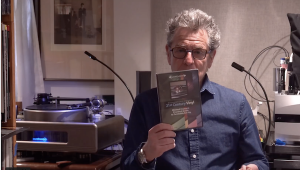

When I sat down at last January's (1996) Consumer Electronics Show with veteran RCA producer Jack Pfeiffer, I had no way of knowing that I would be conducting the final interview he would ever give. Pfeiffer suffered a fatal heart attack on Thursday February 8th, 1996 at his RCA office where he'd worked in the Red Seal division for the past forty seven years. He was 75.

Jack Pfeiffer was a pleasant man, soft spoken and easy to talk to. When my rather limited knowledge of the classical music world became apparent, he picked up the slack so I wouldn't feel too uncomfortable.

My reason for speaking with him had less to do with anything technical, and more to do with getting his take on the work being rediscovered and appreciated by a younger generation of music lovers thirty plus years later, and how, given the usual corporate bottom line mentality (yes, even then) such a dedication to quality could prevail. So yes, it was more People and less Mix and under the circumstances that's fine with me.

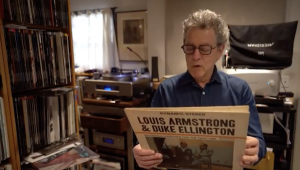

Pfeiffer presided over RCA's experiments with stereophony before a method existed for such recordings to be issued to the public. At a C.E.S. press conference, Pfeiffer explained that his goal in these recordings was to capture the right balance of direct to reflected sound in the auditorium. Music lovers are fortunate that Pfeiffer and the likes of Lewis Layton, Richard Mohr and the others were dedicated to providing listeners with the finest, most natural sound quality possible.

It was the "golden age" of classical music performing and recording with artists and conductors like Jascha Heifetz, Artur Rubinstein, Van Cliburn, Vladimir Horowitz, Fritz Reiner, Charles Munch and the others stepping before all tubed analog hi-fidelity recordings gear in the hands of technically competent, music loving engineers and producers.

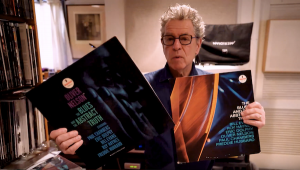

In the case of RCA and its "Living Stereo" program, the entire chain, from the recording engineers and producers to the mastering personnel and pressing plant operators, was dedicated to quality. That is obvious both from the sound of the original "Living Stereo" records and the reissues on LPs from Classic and Chesky Records and on the BMG "Living Stereo" CD transfers which Pfeiffer produced.

That these thirty and forty year old productions are still the measure against which modern recordings are held, and that for many listeners they remain unchallenged as among the finest sounding musical documents ever created, is testimony to the skills and care of all concerned.

To listen to a Heifetz violin concerto on a clean RCA original pressing (Heifetz recordings were unavailable for LP when this was originally published) is surprisingly close to experiencing the virtuoso playing in a concert hall- especially in terms of tone and emotional communication. These are not moldy old recordings mired in noise, distortion and limited bandwidth and dynamic range.

Jack Pfeiffer was born in Tucson Arizona in 1920, studying music and and engineering at the University of Arizona and Bethany College in Kansas. After a stint in the Navy during World War II, he went to Columbia University and also played jazz piano professionally before joining RCA in 1949.

As you'll read, during the pioneering years of stereo recording, Pfeiffer worked in parallel with the mono engineers, putting down on tape some of the finest performances of the classical repertoire ever recorded. When some of these Pfeiffer produced "experiments" were issued, first on reel-to-reel tape, and then on vinyl, they created a sensation in and out of the audio community. They're still doing it forty years later! ("M.H." is Classic Records's Mike Hobson).

M.F.:So I come from the world of popular music-I do love classical music-but I can't say I'm an afficiando like some of these other guys.

J.P.:Oh really?

M.H.:Oh, you're a big collector!

M.F.:Oh, well, I've got a lot of original....

M.H.:You've got tons of original RCAs.

M.F.:And I actually listen to classical music too!

M.H.:This is the guy who went on television (The Today Show) five years ago and said that he sold a copy of Gaité Parisienne (LSC-1817) for $800.

M.F.:Yeah, I did.

J.P.:.....and caused this big controversy

M.F.:Oh, I upset a lot of people. I didn't want to sell it. [laughter] I had gotten it from somebody...

J.P.:Oh, really?

M.F.:for $1.

J.P.:A dollar, oh boy.

M.F.:And I wanted to keep it, but the pressure kept building. I mean to sell it.

J.P.:No, when the price goes that high you can't resist it.

M.F.: That's right and when you write for The Absolute Sound , you know, you need $800, believe me.... Does all this attention now come as a big surprise to you? This whole thing that's happened with these records coming out again?

J.P.: Well, in a way, yes, although it's not a surprise because these have been my favorites for so many years so that I feel that when people do finally get a chance to hear them, that they'll feel the way that I do about them. They are genuinely precious items, and they have to be preserved, and this is one way to do it.

M.F.:Over the years it's gone from the original pressings and the original quality that was involved, down, down down, down. How did that feel?

J.P.:Well it had to do with our marketing people wanting to put out certain things, and they just scheduled things and somebody went in and grabbed the production tape, and transferred it to a Victrola or a Gold Seal, or something like that, without paying too much attention to what they were doing.

M.F.:Right.

J.P.:Rather than going back to the original masters and trying to extract all of the quality that was in the original recording.

M.F.:That must have been frustrating given all the work that went into it.

J.P.:Well, yes.

M.F.:At the bottom of that pit, did you ever think there was gonna be a way out?

J.P.:Well, I felt we had a chance with CD to preserve it in what I consider to be a much more endurable product.

M.F.:Right.

J.P.:And it wasn't subject to the frailties of our (LP) manufacturing methods

M.F.:Right.

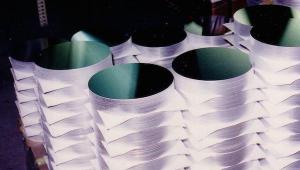

J.P.:And our vinyl processes where we had the feeling that they were using, you know, floor scraps.

M.F.:Right. Sometimes I bet they were!

J.P.:Or scrapings for the vinyl or chopping up labels and incorporating those into the...I mean that was the main problem with the generations of the various releases.

M.F.:Oh sure.

J.P.:Because the master tapes were still pretty good. They were what created the original "Living Stereo" and the original "shaded dog".

M.F.:What was the corporate environment when you first started doing this? RCA was still a corporation. It was a fairly big company.

J.P.:Oh yes.

M.F.:But how do you explain the corporate ethics act that allowed you to really do such high quality work?

J.P.:Well, we had a vice president in charge of the record division who had quality on his mind, and he knew, and I don't think he especially was endowed with that, with that desire, but it came from the top from General Sarnoff who felt that the records were great publicity items and that if we had great quality, and if we had the quality artists primarily, that it would reflect onto all the other RCA products. And that's why he said "Go get Toscanini. Go get Heifetz, Horowitz Rubinstein. Get all these great superstars, and I don't care what it costs." And he had to pay plenty to get them!

M.F.:Yeah, I'm sure.

J.P.:But by virtue of their being exclusive to RCA, it would reflect on all the other products that RCA was making.

M.F.:Now what about the high quality of the recordings? Columbia had some good artists. Most of those records are a dime a dozen, and no one cares about them.

J.P.:Well, again, as I say it started with the General, and it reflected on down, and we had a vice president who was a little bit in awe of General Sarnoff. We all were, of course, but he realized that we had to maintain not only a high quality in as far as the artist was concerned, but a very high quality as far as the product was concerned, and he constantly drove us like crazy --George Marek -- he drove us to do things and gave us money to do things, not always wisely, but at least it was an effort.

M.F.:Who invented the "Living Stereo" logo?

J.P.:Well, it came up from our publicity department, and we're sitting around talking about it, and they wanted to call it, again, you know, RCA was famous for its "Orthophonic" sound....

M.F.:Right.

J.P.:Then it's "New Orthophonic", and they said we should have stereo, and we did have "Stereo-Orthophonic" for the tapes.

M.F.:Right.

J.P.:And they said, well, let's call it (the records) "Stereo-Orthophonic", and I said "Come on. Enough already, what we're trying to do is to emphasize the fact that this is more like a live audio sensation."

M.F.:Right.

J.P.:They scratched their heads and said, "Well, let's call it 'Living Stereo' then." I said, "Well, I think that's fine," and our art department came up with a wonderful logo.

M.F.:Yeah, I'm old enough to remember that when it first came out.

J.P.:Oh yeah it was good—spectacular—and all of the first releases both in the Red Seal and the pop department were Living Stereo.

M.F.:One of the questions that I got asked by someone at a party last night was "How is it that all those popular and jazz ('Living Stereo') recordings sound so good also?" How much of what you did crossed over to the pop side, 'cause that's what most of our readers are really gonna be interested in knowing.

J.P.:Well I was trying to emphasize the simplicity of microphone placement or microphone use, because I said the more microphones you use, the more likely you are to get phase distortions, and things that- you don't really know what you're doing. You know, because every microphone picks up every sound in the venue, and when they get all blended together, it's going to be a terrible mess.

M.F.:And when you all heard that....

J.P.:And we all heard that - yes; and, of course, this is a battle that I've been raging for the last 50 years almost!

M.F.:I think you've won that battle at this point.

J.P.:Well, I think so too, because I think that digital recording has really emphasized the fact that you've got to limit the number of microphones.

M.F.:Well, that was the frustrating thing for a lot of us audiophiles, because we heard how bad it was in the 70's. We complained and complained, and we weren't listened to. We were put down and then all of a sudden with digital recording, all of a sudden there were people saying, "Well now for the first time you can hear the problems with the microphones and the phasing." We heard it all along.

J.P.:We heard it all along too!

M.F.:And were laughed at! Now all of a sudden!

J.P.:Yeah, I know. Very frustrating.

M.F.:So did you have any supervision and oversight on the pop side as well?

J.P.:Not directly, although the engineers who were working with us were also working for the pop people, and the head of the engineering department was very, very quality conscious too, and he came to every Red Seal session, and he supervised sort of, all the technical aspects of it. He'd sit there and actually test the tape to make sure that he was getting the best noise-free batches of tape, you know, because at that time tape quality was a little bit, well, uncertain. And he would sit there and roll those tapes through before the session started and put aside those that had the best noise characteristic.

M.F.:And the ones that didn't went to the pop side! [laughter].

J.P.:Well, not really. Of course, that only counted for one aspect of the quality because low noise was good, but the important thing was the engineers who worked with us also did the pop work, and they were, of course, at that time recording everything together- they weren't doing all this (multi-) tracking.

M.F.:That's back when everybody could play.

J.P.:That's right they could play, and they had the big band era, you know, and they were doing the ballads with Perry Como and even Elvis did some of it.

M.F.:Were you around when he showed up there?

J.P.:Oh sure.

M.F.:What was that scene like?

J.P.:Oh that was something! It really was because, and, you know, you'd see him in the hallways and not pay too much attention to him, but then over the years when you realized that his participation in RCA really kept us alive.

M.F.:Did you ever get his autograph?

J.P.:No, never. I never got anybody's autograph. I'm not an autograph fiend.

M.F.:Yeah.

J.P.:I do have some. I have Horowitz, I have Heifetz, I've got Rubinstein and Leontyne Price, and Van Cliburn and Piatagorsky. Those are sort of my favorites, you know, and people I got very close to in working and so, I like to have my little rogue's gallery with their pictures and their autographs.

M.F.:I'm sure it must be a nice thing to have to remember.

J.P.:It is.

M.F.:So, how big were the production teams? Let's say you were doing a project.

J.P.:Um-hum.

M.F.:You traveled around the country to the different venues where these recordings were made.

J.P.:Um hum.

M.F.:And all the equipment was shipped by truck?

J.P.:Yup.

M.F.:Like to Chicago's Orchestra Hall?

J.P.:We did have some equipment at that time in Chicago, because we had a Chicago studio, and there was some three-track equipment in Chicago that we were able to use, but this was only later, of course, in '56, '57 and after that. Earlier we sent everything from New York because we had a very limited supply of stereo equipment and that's why not everything was recorded in stereo, because even though I screamed and hollered and said "We've got to do everything in stereo," the equipment was not available all the time.

M.F.:Now your job was to produce these sessions.

J.P.:Um hum.

M.F.:So that meant?

J.P.:Well, we had two teams. We had a mono team, and we had a stereo team. And generally the mono team was the product that was going on the market, so Richard Mohr and Louis Layton were handling that. He (Mohr) would work with the artists directly, working out the takes, so in a sense I really didn't produce those sessions.

M.F.:Right.

J.P.:I produced the stereo because I worked with the engineer to set up the microphones, and I supervised him when we were recording. We did very little monitoring (because) we didn't have that kind of equipment.

M.F.:So basically there was a dual track system.

J.P.:Yes.

M.F.:So Mohr and Layton were....

J.P.:They were doing a mono totalled (mix), and then we were using another console and different microphones and a different monitor system in a different location in stereo.

M.F.:Wow.

J.P.: You see, and it was expensive, of course, to do that but.....eventually I put together a demo tape, starting off with, of course, the opening to Also Sprach Zarathustra, and I remember one of our executives listened to it and he said, "What's that hum at the beginning?"

M.F.:That's how I got a copy of that for $10! Somebody said, "I got a copy of this I reckon you might want, but it's got this noise at the beginning." [laughter] "I think it's wind or something, I don't know what, must be defective."

J.P.:Really. But I would drag people into our listening room, and I had the setup constantly going and anytime anyone in management was around, I'd say, "You've got to hear this."

M.F.:I do that today with that recording!

J.P.:I'm sure.

M.F.:People go crazy.

J.P.:That's the only way to do it, you know, get people fascinated with it. I'm still doing it too.

M.F.:That's good.

J.P.:Because we get new equipment, and I bring them in. I want them to hear what it's doing, so I think they were all in agreement, but they knew that it was a slow process, and we couldn't just suddenly start recording everything in stereo. The pop department was, of course, the most profitable part of the company.

M.F.:Always was and always will be probably.

J.P.:Yeah, and they wanted to make sure that the stereo was well distributed to the pop people, and if there was any conflict, you know who won out.

M.F.:Yeah. At first these stereo recordings were just released on tape?

J.P.:Yes. That's right. In the '50s, 55-56, we released- well they turned out so well, our experiments, that they decided to release them.

M.F.:And those were expensive.

J.P.:Yes, they were.

M.F.:They cost $12 or $13, originally.

J.P.:Yes, and that was a lot of money then.

M.F.:So mostly doctors got those. [laughter]

J.P.:They also made some stereo tape cartridges and they had a big massive machine that played them. It was sort of the beginning of the cassette era.

M.F.:It was before Elcaset. It was something else entirely?

J.P.:It was before that, yeah.

M.F.:That I'm not aware of.

J.P.:It didn't last very long, because people would have to buy the whole machine, and they'd have to buy an extra amplifier, and an extra speaker, and it was too complicated.

M.F.:Yeah, well you needed some of that for stereo anything.

J.P.:A lot of people didn't feel it was worth it, and I don't know, it probably wasn't at that time.

M.F.:Now, were all those tapes (being used for the Classic "Living Stereo" vinyl reissues) stored properly?

J.P.:Well, I don't know how properly they were stored because we've never really had a strict humidity and temperature- controlled environment in which to store tapes. And, of course, as you know, it's a physical property and when temperature and humidity change why it's bound to change.

M.F.:But you didn't do what Atlantic, unfortunately did, which is to store all their out-takes in a department store wood frame building in someplace in New Jersey that burned down. You didn't do that.

J.P.:No, no, no.

M.F.:Can you imagine that? I mean is that nuts?

J.P.:I don't believe it. They did this?

M.F.:Yeah, they had a fire and they lost everything.

J.P.:Oh, my.

M.F.:Everything that wasn't issued.

J.P.:Oh no.

M.F.:It's gone.

J.P.:Well, we had a similar tragedy. At a certain point we had some new engineering moguls in here who realized that we were just building up tapes like crazy, and they wanted to cull through all of the tapes and throw out those that were not going to be used. Well, who knew, you know? And they kept what we call the work part, which was the original master from the recording session, edited together.

M.F.:Right.

J.P.:They kept that, and they usually kept the remaining, what we called the prime tapes, because we always recorded to a prime and an alternate. This goes back to the days of 78 when they recorded on two machines.

M.F.:Yeah.

J.P.:The dash 1 and the dash 1A, and so they kept all of the remaining parts of the prime (tapes) so if something happened to the work part, they could go back and re-edit it from the prime tapes, but they discarded the alternate tapes in some cases but not all. Then they also [chuckling] we had paper boxes, you know, cardboard boxes that tapes came in, and we would write on the back of them what they were, when it was recorded, who was involved and all sorts of things. They took all the tapes out of those boxes and put them in metal cans with the idea that they'd have a better preservation quality, but all of the information on the back of those boxes was thrown out! All they kept was the number, and then we had to depend their being accurate.

M.F.:Oh, boy.

J.P.:So we've been going through a lot of problems with that.

M.F.:And I understand metal cans also have problems. There are certain....

J.P.:Well, these were aluminum cans.

M.F.:So that?

J.P.:And I think the theory was that they would be better preserved by being in these cans, but they didn't do it to all of them. At a certain point they stopped and, you know, when you've got such a big organization, there are all sorts of people who have their two cents worth.

M.F.:Well at the networks they erased all the videotapes for all the TV shows for years. I mean thank god you didn't do that.

J.P.:Oh, thank god! But fortunately we are finding I'd say 95 - 98% of the original work parts.

M.F.:Wow, that's good.

J.P.:For these recordings and, of course, that's what Mike (Hobson) is using for his production, and that's what's we use in digital re-mastering for our CD releases.

M.F.:Now the 1954 Zarathsutra : there's all kinds of stories about the tape of that having gotten partially erased, someone left it on top of a loudspeaker, and what they are using is a 1/4 inch 15 IPS copy......

J.P.:No, no, no, no.

M.F.:No?

J.P.:No, no, no, no. Actually, what we did at that time, we- nothing was erased, but before the master tapes were used for records, of course, we were using them for the open-reel tapes, and so we used that as the high-speed master -- the original edited tape for the high speed master.

M.F.:So it was run many times?

J.P.:Yeah.

M.F.:That was a gutsy thing to do.

J.P.:It wasn't. I mean it was preserved in a sense. It wasn't destroyed just by playing it.

M.F.:Right.

J.P.:Although probably some of the quality of it was, but that's what we have been using, and that's what Mike used for his production.

M.F.:That's one record that for me the original sounds much better than the reissue for some reason.

J.P.:Really.

M.F.:A lot more was lost in that one for some reason, perhaps from being played so much. What about the controversy of a lot of people saying that these re-issues sound too bright and too "solid state".

J.P.:On what, on the vinyl?

M.F.:Yeah, on the vinyl.

J.P.:Oh. I don't think so, and I have friends who are what I call Hi-Fi-natics [laughter], who I've given these pressings to, and they have the CDs of them and they've compared them. They say, "No, no, no. They say vinyl is even better than the CDs."

M.F.:Oh, I think that also, but there are some people who say that what Classic should have done was try to recreate what the original records sound like.

J.P.:Oh, no, no, no.

M.F.:Which were, as I understand it, somewhat compressed, and the bass was summed...

J.P.:Why, yes. They had to be tailored to the deficiencies of the cutting and the playback system of the day. We used to listen to lacquers. I mean they put the master together, they'd transfer it to 1/2 inch tape as a production master, they'd cut a reference lacquer, and we would listen to that on our own systems, you know, in the office and also at home, and we'd make judgments about whether or not it needed- whether the compression was too great or whatever, because when the mix down was made to make the production master, they tried to limit the bass, they tried to limit the dynamics, and to some extent, they tried to limit the high frequency content at the end because they knew that that was going to be on the inside (center) of the record.

M.F.:Sure, yeah.

J.P.:And we would listen to that, and if we felt that that was too great, or if the level wasn't good enough or if the- whatever the sound was-we made a judgment based on what they cut.

M.F.:It was done because you had to, because of what it was being played back on?

J.P.:Sure.

M.F.:The original recordings were made to be as good as possible.

J.P.:Of course. And with a wide range, a wide range as far as dynamics and frequency were concerned, but when we had to put it onto a record which had limitations, both in the cutting and the playback, you know, then we had to take the record and make the judgment based on that quality, and that's what came out on the original "Living Stereo".

M.F.:So the people that think the originals are the holy grail, those are the magic, they're mistaken?

J.P.:They are totally mistaken.

M.F.:That's my position on the whole thing, and you wouldn't believe the kind of abuse you get for having that position.

J.P.:[laughter] Well you see people get used to a certain quality, and if they've listened to something for a long time, they feel that that is the true quality that expresses their position.

M.F.:Their position-these people's position as I understand it, is that you guys were making these recordings as raw material and then you were tailoring it to make it sound as good as possible, period!

J.P.:No.

M.F.:That's not what it was. What you were doing is making the recordings sound as good as possible, and that if you could have done the straight transfer right across to vinyl like they're doing now, you would have.

J.P.:Like they're doing now.

M.F.:You would have done that.

J.P.:And that's what we're doing for the CDs too.

M.F.:Right.

J.P.:Because we're not limited to any kind of restriction.

M.F.:Now here is the question for you that I need to get answered.

J.P.:[chuckling] Okay.

M.F.:BMG is a company with a lot of money and a lot of resources.

J.P.:Yeah.

M.F.:Yet all of the transfers that they're doing that I can find out about on the pop side, and I guess on the classical side, are stock Sony 1630 transfers. That's the converter they're using.

J.P.:Um hum.

M.F.:Now, surely they have the money and the facilities and the ability to listen to some of these much higher tech processors that are out there. Are they convinced that there is no difference in the sound when you could go to a stock 1630 processor as opposed to a Wadia or an Apogee or- any of these.....

J.P.:But we're using Apogee.

M.F.:You are?

J.P.:Oh, yes. We've been using an Apogee for some time now.

M.F.:Not on the pop side from what they're telling me.

J.P.:I don't think so. I don't know. See now BMG is two different companies, I mean as far as the record division is concerned, we have nothing to do with the pop end. Not a thing. In fact, if we want to release something that was originally in the pop department we have to go in as a client and....

M.F.:We being RCA?

J.P.:RCA Classics.

M.F.:Okay. Why would you want to release anything that was on the pop side?

J.P.:Well, we have. Like we released the Belafonte Return to Carnegie Hall on our "Living Stereo" series, and I tried to put together a Christmas record of all the famous old Christmas songs by the various people for Red Seal, for a classical "Living Stereo" release and got up to a certain point, and they decided "No. You can't do that."

M.F.:So is the Heifetz stuff ever gonna come out on these records? Do you think eventually?

J.P.:Uh, that depends on the contracts. Now, Jay Heifetz, Jascha's son is sort of in control of that whole thing, and he signed a contract with BMG to restrict somewhat the freedom of doing things like that. I would think that at a certain point, he will recognize that that is a viable way of expanding his father's recorded output, you know.

M.F.:Yeah.

J.P.:In fact, we put out one Living Stereo of Heifetz, you know, the Brahms and Tchaikovsky (violin concertos).

M.F.:Right. It's the 2 in 1.

J.P.:With Reiner, and that was before the contract was drawn.

M.F.:Oh, it got pulled off the market?

J.P.:No, no, no. He left it on, because it's the best seller of all of the "Living Stereo" CDs!

M.F.:I'm not surprised.

J.P.:And our Heifetz collection....

M.F.:The box set?

J.P.:The 65 CD collection is, it's a miracle really. It's the most incredible thing. I get cold chills every time I think of it.

M.F.:And that sells too?

J.P.:It has sold out because it was a limited edition.

M.F.:So now it's time to put them on records!

J.P.:Oh, well of course. I'm totally in favor of it, and I will certainly make it an issue with Jay.

M.F.:Now you're playing those back in the studio on a tubed tape recorder when you do the CD transfers or no?

J.P.:Yes.

M.F.:And Classic is using solid state?

J.P.:Yeah.

M.F.:Does that make....

J.P.:I don't think that matters too much. No, we're trying to duplicate the actual conditions of the recording, and think it's a good idea, and so far we have the equipment, so why not use it? I don't think they have the equipment.

M.F.:What percentage of the "Living Stereo" catalog has come out on CDs at this point? What about the "Dynagroove" stuff?

J.P.:Well, we'll get into that, but all the "Living Stereo" was not of the same superb quality.

M.F.:Right.

J.P.:It varied greatly. Even at the beginning because we were recording things and sometimes they didn't turn out too well, but they still went out as "Living Stereo".

M.F.:Right.

J.P.:There was no technological profile that specified that this is a "Living Stereo" record.

M.F.:It was an esthetic concept more than anything.

J.P.:That's right.

M.F.:Like all the companies that have these kinds of names for their so-called recording process.

J.P.:Yeah, that's right, and so I don't want to put everything out on "Living Stereo" because some won't represent what I think are the true historic releases. And that I think I said at the outset when we started with the "Living Stereo" reissues, I said, "We've got to find the original tape; they've got to be great performances; they've got to be by great artists, and they've got to have great sound."

M.F.:Well, you've got a pretty good catalog to work with then!

J.P.:Well, we have, yes, fortunately. Although, surprisingly enough, I was against putting things out as "Living Stereo" because I said, "Well, you know, Mercury came out with its 'Living Presence'. This will just look like we're jumping on the band wagon, and 'Living Stereo' wasn't any great technological improvement."

M.F.:No, but it had, it was a......

J.P.:And then I got to thinking, but, you know, we've got the artists. We've got the sound.

M.F.:And what does Papillon (the name given to the first reissue series) mean anyway. What the heck was that (aside from meaning "butterfly")?

J.P.:Well, another one of those things.

M.F.:Another one of those things. And when I saw that butterfly logo, as a fan of these "Living Stereo"s, that original logo as an eight-year old, a ten-year old whatever it was, I was like ten years old when Belafonte at Carnegie Hall came out. That logo literally got me excited when I saw it back then! So to see that abandoned in favor of a butterfly!

J.P.:Why, sure.

M.F.:And it still does (excite me).

J.P.:Right, you were imprinted with that logo.

M.F.:That's right.

J.P.:And that was the idea, of course. We didn't realize it was going to be as popular as it turned out to be.

M.F.:Isn't that always the case. You never know what you do when you're doing it.

J.P.:You never know what you're going to end up with, but if you have your instincts right, and you keep pushing for the right quality and the best sound, and the best conditions constantly, then......and I keep doing it even to this day after 47 years.

M.F.:That's good. That's what you should be doing.

J.P.:It's giving me a great deal of satisfaction to see these great recordings coming out.

M.F.:It's got to be, and a whole new generation of younger people enjoying them.

J.P.:I know. It's surprising. It really is amazing, and having them come out on vinyl is also a great thing. I've been encouraging our German people, they're also very interested in putting a whole vinyl series of "Living Stereo" out.

End of Part 1