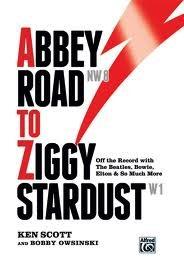

"Abbey Road to Ziggy Stardust": Engineer/Producer Ken Scott Looks Back On An Amazing Career (so far).

Ken Scott's unlikely story alone would make for an interesting read: how at age 12 he asked for and got his first tape recorder, how he hated college and ended up sending letters to every record label and radio and television station (how many were there in the U.K. at that time?) looking for a job and how on January 22nd of 1964 a few months short of his 17th birthday he received a response from EMI studios and how within three days of being hired to work in the tape library he had in his hands a 4-track Beatles master tape (containing German language versions of some hits along with "Can't Buy Me Love" recorded in Paris at EMI's Pathé Marconi Studios)!

A month later he met The Beatles heading towards him in the studio to record the songs for A Hard Day's Night. Soon he met engineer Norman Smith and later graduated to becoming a "button pusher" in the studio where he witnessed the creation of more iconic Beatles albums, as well as albums by The Hollies, Manfred Mann and other EMI acts. Does the thought of reading a first hand retelling of this unlikely tale now interest you? If not, perhaps you're not a candidate for this book.

But read on first before deciding: from there, after the completion of Rubber Soul Scott became a cutting engineer, taught by Geoff Emerick. Remember, this was November of 1965 a little more than a year after his unlikely start at EMI. Scott's telling of that part of his career was rather flat. While it's of greater interest to us record fanatics, he was obviously more interested in getting to the next plateau.

One of the first startling facts Scott divulges is that EMI's Motown issues were cut from vinyl sent overseas from Detroit! The records were transferred to tape and then cut. No wonder those fold-over original EMI UK Motown records don't sound so hot!

In 1967 Scott was promoted to recording engineer and his real fun begins. Of course Sgt. Peppers... had already been recorded, so Scott started in the middle of MMT but he was there for the previous albums and there are many great stories you're sure to want to read. He was the mixing engineer for the mono mix of "I Am The Walrus" and there's a great story. Ringo turned the radio dial as the song was mixed and found the BBC production of "King Lear" heard at the end. John said "use it" so they did, mixing it in "live."But since it was for the mono mix, when Geoff Emerick later did the stereo mix, he was forced to splice in the ending from the mono mix, which is why at the end the song goes from stereo to mono. More recently when the song was used for the Love surround re-mix, permission was granted from the BBC, which supplied the "King Lear" audio so the end could be remixed in stereo and surround sound.

And of course he was at the controls for The Beatles ("The White Album") and there are some great stories there!

Scott's are effective because his are both technical and personality-driven. If you've read some of the other books on Beatles recordings, perhaps you know some of this, but the drums for "Mother Nature's Son" were recorded in a staircase and though they sound like tympani, they are not. About a minute into the song there's a clicking sound. It's Paul tapping a pencil on a book. It wasn't in the original recording. Paul tapped during playback and then requested it be added to the final mix.

I could go on but instead let me list some of Scott's other recordings: Jeff Beck's Truth, Procol Harum's A Salty Dog, George Harrison's All Things Must Pass (after being fired from EMI and joining Trident), the first America album, Son of Schmilsson, the orchestral dates for Sticky Fingers ("Moonlight Mile" and "Sway" (good sounding strings!), and of course David Bowie's Hunky Dory, Ziggy Stardust... and Alladin Sane and the Bowie produced Transformer for Lou Reed. Did you know that the "colored girls" who sing background were white and two were Jewish? Scott recalls how and why the background vocals go from way back to in your face.

Scott engineered Elton John's Honky Chateau and Don't Shoot Me, I'm the Piano Player and would have done Goodbye Yellow Brick Road too except for one of many money screwings he recounts in the book, which includes plenty of personal high drama along with the celebrity stuff, minus most of the bitterness that sometimes accompanies memoirs like this. Oh, he spews a few times but for the most part, he avoids the bile and he also avoids self-aggrandizement.

Scott also engineered The Mahavishnu Orchestra's Birds of Fire along with many other jazz and jazz fusion albums and of course Supertramp's Crime of the Century as well as The Dixie Dregs' What If? and so on.

Are you detecting a pattern here? Yes, Scott has recorded so many audiophile 'faves' it's difficult to keep count. How he did it and the background stories involved do make for a thoroughly engrossing "page turner" for the right crowd and that crowd includes analogplanet.com readers, that is for sure.

The story charts Scott's move from engineer to producer when he realizes he's being one and not getting the credit or the money. Eventually Scott and his wife move to Los Angeles and guess what happens? Drugs (not used by Scott by it's all around and affects what happens in the studio) and a divorce (Scott eventually remarries).

His time in Los Angeles makes for some of the most interesting reading (especially if you were there at that time as I was) as he takes on the job of developing, recording and managing the ill-fated band Missing Persons, and after doing all of the hard work helping them to "break," they 'reward' him by dissing him and making their own disastrous career moves but not before he hosted an infamous party for the band at which a party crashing kid gets his balls stuck in the swimming pool intake port.

One of the final chapters titled simply "George" recounts his final encounter with George Harrison, some thirty years after they'd last met at A&M during the making of Crime of the Century. Scott moved into Harrison's estate to organize his vast tape library and prepare for the 2001 reissue of All Things Must Pass. It's a poignant story because by that time George was seriously ill. Scott recounts being there the day he left his estate for the last time. Written with the help of writer/producer Bobby Owsinski, Ken Scott's "Abbey Road to Ziggy Stardust" is one of the most enjoyable industry memoirs I've had the pleasure of reading, both because Scott's story is so damn interesting and unlikely and because he blends perfectly the celebrity "inside poop" and the technical recording trivia that add useful dimensionality to many of your favorite recordings. What's that telephone ring doing at the end of Bowie's "Life on Mars"? Read the book and find out.

Any criticism? Only when Scott writes about how music "used to be on vinyl". His stories about the difficulties working with tape will make you understand why so much today is done digitally, but he does write that transferring analog to digital track by track made him realize that something not so good happens in the process. Single tracks sound okay, he writes, but all together they lose the magic.

All I can say is, if you've read this far, you really need to read this book. It will expand your understanding of some of your favorite records and acquaint you with one of the most engaging and talented recording engineers of rock's "golden age." The book includes a discography, glossary and many photos and career documents and mementos.

I will post the audio of an interview I conducted at "The Fest For Beatles Fans 2013" in Secaucus, NJ with Mr. Scott earlier this month. Asked by a fan at the convention how he managed to get hired by EMI at 16 and become a Beatles engineer a few short years later he began by saying "I've been asking myself that same question for years". He then pointed to the sky.

Perhaps his beginnings were God's intervention but from there, if you're familiar with his recordings, you know his path was talent driven. He's also one of the nicest people you're likely to meet.