Preaching And The Blues: The Folk Blues Career of Son House

I’m gonna join the Baptist Church

I wanna be a Baptist preacher so I won’t have to work

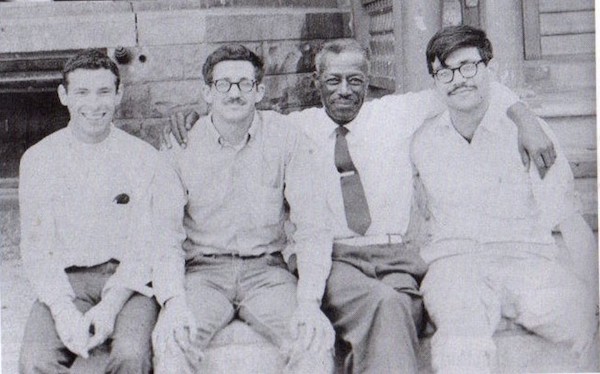

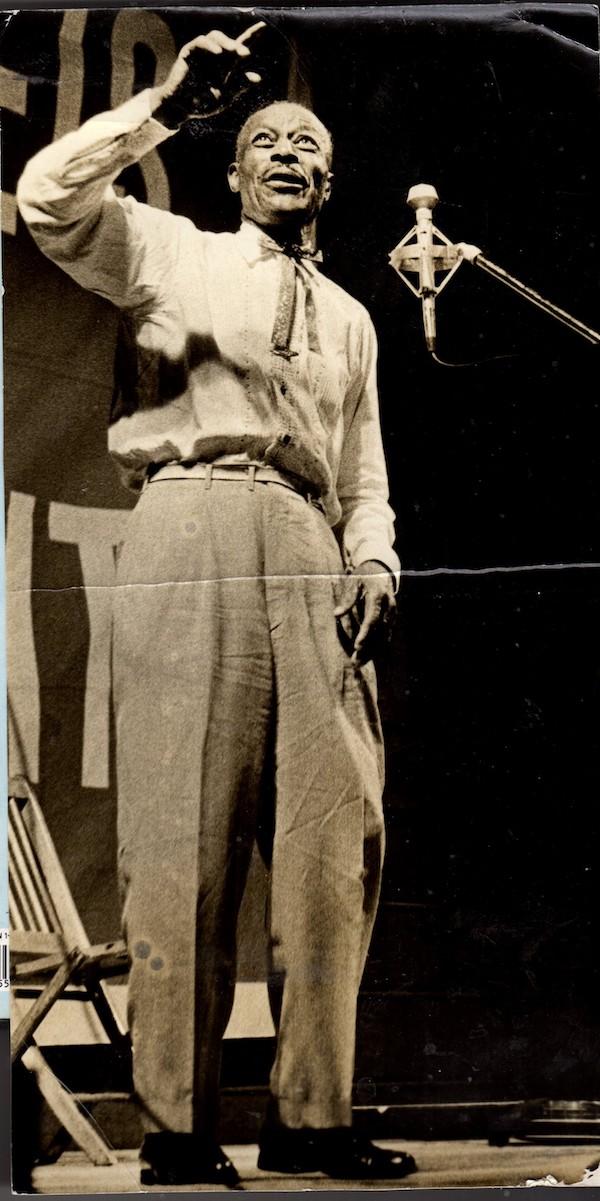

In June 1964, Nick Perls, Dick Waterman, and Phil Spiro, three young white men from the North, traveled to Mississippi in search of Son House (1902-1988), a blues singer/guitarist whose career had been so abject a commercial failure that he was completely forgotten and unknown, except to a small group of perhaps two dozen country blues collectors who, based upon the recordings available, maybe twenty minutes in total, had proclaimed him to be the greatest of all the Delta Blues singers.

House, the son of a preacher, had become a Baptist preacher at fifteen and in a 1965 interview stated, “Brought up in church and didn’t believe in anything else but church, and it always made me mad to see a man with a guitar singing these blues and things. Just wasn’t brought up to it. Brought up to sing in choirs. That’s all I believed in then.” House remained a believing Baptist until he died, and his view of the blues never changed, even after hearing a guitarist play at a juke joint in 1927 and having a “reverse born again” experience.

He purchased a guitar and quickly became proficient. “I’d set up and concentrate on songs and then went to concentrate on me rhyming words, rhyming my own words. ‘I can make my own songs,’ I said. And that’s the way I started.” Soon he was playing and singing in jukes himself. “Them country balls were rough! They were critical, man! They’d start off good, you know. Everybody happy, dancing, and some guy would be outside selling his corn whiskey… and then they’d start to getting louder and louder… they’d start something then. Be some running done! Sometimes we’d almost leave our guitars behind…. Lots of times I knew lots of people to get killed.” Later that year, he killed a man in a juke fracas and was sentenced to 15 years at the brutal Parchman Farm. Some sort of political intervention got him out after two years. Again, he tried to live the Christian life and was even the pastor of a church for a while, but went back to the blues, even though he’d been preaching against that life and knew what it would lead to. “I was just ramblified, you know. Especially, after I started playing music. We just didn’t want to be stationary, to be obligated to anybody. We figured we could make it better without plowing so much.”

You know, one deacon jumped up and he begin to grin

Yeah, one deacon jumped up and he begin to grin

You know he said, “One thing elder, I believe I’ll go back to barrelhousin’ again

After being recommended by legendary Delta bluesman Charley Patton, House recorded four 78 rpm records for the Paramount Company in May 1930 and was paid $40. House’s intense, church-influenced “preaching” blues style was far from the up-tempo, dance, party tunes that were popular, and the records were issued just as the Depression began to impact southern blacks who were nearly the sole market for country blues. “The way I figured it out after that, after I started, I got the idea that the blues comes from a person having a dissatisfied mind and he wants to do something about it. There’s some kind of sorrowness in his heart about being misused by somebody.”

Probably a few hundred copies or less of each record were sold. A generous estimate is that fifteen copies exist today of all four Paramounts, and there is only one copy of “Clarksdale Moan”/“Mississippi County Farm Blues,” not found until 2006. His recording career was over, and it was a failure, but House hadn’t expected much and was used to little. “Making it that easy and that quick, it’d take me near about a whole year to make forty dollars in the cotton patch. I was perfectly satisfied. I showed off a whole lot with that when I got back to Lula, Mississippi.” House gave up blues playing, went back to preaching in the Baptist Church, and tractor driving.

In about 1934, the Baptists threw him out of the pulpit for playing blues at parties and jukes. “So, I took a little nip. None of the members were around, so I took the little nip. And that one little nip called for another big nip…And I began to wonder, now how can I stand up in the pulpit and preach to them, tell them how to live and quick as I dismiss the congregation and I see ain’t nobody looking and I’m doing the same thing. I says ‘That’s not right.’ But I kept nipping around there and it got to be a public thing… So I got out of the pulpit.” In 1941, accompanied by Willie Brown, he of “You can run, you can run, tell my friend Willie Brown” “Crossroads Blues” fame, and again in 1942, House was recorded by Alan Lomax for the Library of Congress, near Robinsonville, Mississippi. For the approximately one hour of music recorded, House was rewarded with a bottle of Coca-Cola. After that, there were no recordings and no information and soon Son House was a legend, but only to so few that it barely mattered.

You know, one sister jumped up and she began to shout

Yeah, one sister jumped up and she began to shout

She said, “I’m so glad that this corn liquor’s goin’ out”

In 1963, rumors—picked up by interviewing blues singers and door to door research—began circulating among country blues collectors that House might be alive and living in Robinsonville. During the dangerous “Freedom Summer” of 1964, for reasons they could not have explained and made sensible or even understandable to family and friends and certainly not to a Mississippi policeman, Perls, Waterman, and Spiro decided to search for House. There was no commercial market for country blues except a small club scene, a few folk festivals, and some small collector-run record labels. None of them were in the music business or were musicologists or folklorists. The expedition was likely to be fruitless, certain to be tedious, and possibly very dangerous. They probably would have said they were on a mission to find a legend whose music had shaken them and changed them and to bring back that legend’s music to “the world.” They never seem to have contemplated that House might not want to return to singing the blues or be in their world.

They drove to Memphis in Perls’ VW and contacted Reverend Robert Wilkins, who in 1929 had recorded “That’s No Way To Get Along” which the Rolling Stones nearly forty years later covered as “Prodigal Son.” It was fortunate that he agreed to help them because their mission would not have been successful without him and could have ended badly or even tragically. Black people in Mississippi were reluctant or unwilling to talk to white strangers, especially northerners, for fear that white employers or the police would think that they were involved with civil rights workers and job loss, harassment or worse would result. Wilkins, a black Mississippian minister, set them at ease and they talked freely to him and answered his questions. More importantly, he handled communication with local white people which required both nerve and familiarity with the complex, unwritten rules of segregation.

After many false leads and much canvassing, they found a man who had been married to House’s stepdaughter and he provided a phone number for her in Detroit. She told them that House was alive and living with her mother in Rochester, NY in an apartment without a phone but could be reached by calling a neighbor. They made the call and House came to the phone. One can imagine the three of them huddled around the receiver, exchanging looks of triumph and amazement and trying to wrestle it away to ask the next question as House confirmed that he was the same man that had recorded for Paramount and Lomax, yes, he knew Charlie Patton, yes he knew Robert Johnson and had even taught him. That same day, Sunday, June 21, 1964, in Philadelphia, Mississippi, civil rights workers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner were murdered by the Ku Klux Klan.

“I just got tired of the mess they’s putting down for years and years. I said it’s time I’m getting out of there. Live in this stuff the rest of my life? What it was it was low wages and wasn’t treated as a human being should be.” House moved to Rochester in 1943 to get away from Jim Crow Mississippi and to work for the New York Central Railroad, first as a rivet heater and later as a porter on the Empire Express run to Chicago. In 1952, House received a telegram informing him that Willie Brown had died. “I said, ‘Well sir, all my boys are gone’ That was when I stopped playing. After he died, I just decided I wouldn’t fool with playing anymore. I don’t even know what I did with the guitar.’ Not surprisingly, he returned to the church. At a labor camp on Long Island in 1955, he killed another man, plead self-defense, and was exonerated by a grand jury.

In 1957, the railroad laid him off and after that, he worked in a department store and a railroad shop, as a cook or dishwasher at a Howard Johnson’s restaurant and as a porter in a restaurant. In June 1964, he had been unemployed for three years and was surviving on a small railroad pension. He was 62 years old and it’s impossible to know what he thought about the prospects for the rest of his life, but he must have known they were bleak. But now, there were these strange white men from the north telling him that they had gone to search for him in Mississippi, that some white people liked that old-time music he had played for the black folks at jukes and frolics and that some of these white people considered him a legend and might pay to hear him sing and play. The white men told him that they were leaving Memphis immediately to drive to Rochester to meet him. What could House have thought about this incredibly unlikely news? Probably, he thought the white men were not going to show up. It was all, if not an outright prank, an example of the arcane manipulations of “white people business” and unlikely to benefit him. White people being what they were, who knew what they wanted?

I’se in the pulpit, jumpin’ up and down

Yeah, I’m in the pulpit, I’se jumpin’ up and down

My sisters in the corner, they’re hollerin’ Alabama bound

Two days later, Perls, Waterman, and Spiro arrived in Rochester. House had not played guitar in at least twelve years and had forgotten almost all of his repertoire. They played some of his Paramount recordings for him, but he didn’t recognize them, saying, “That guy’s got some of my words.” House had a tremor in one of his hands that greatly affected his guitar playing and not only was the precision and subtlety of his playing on the Paramount and Lomax sessions gone, but he couldn’t play even passable renditions of the songs. It also became quickly and sadly apparent that House was, in the words of Dick Waterman, “a total and hopeless alcoholic.” While two drinks stilled the tremor, so that he could play competently, if more alcohol was offered, he would drink until he was unable to play at all. Amazingly, House’s voice, a magnificent instrument in 1930, was just as powerful in 1964 and had gained in richness and character. The voice was enough to convince Perls, Waterman, and Spiro that he could perform again. House said he was willing to try. How could he have said “no”?