The Rolling Stones in Mono Box Set Reviewed

So groups like The Beatles and The Rolling Stones—as well as their producers, engineers and manager—were far more concerned about the mono mixes than they were about the slapdash stereo mixes produced later, often without the group’s participation. This was also true of Bob Dylan, who after attending the mono mixing sessions of “Blonde On Blonde” left Nashville, leaving to others the stereo mixing chores. Of course in the case of The Rolling Stones, the early albums were never released in “stereo”.

Fine, but what does that have to do with today’s listening, which is almost exclusively stereo? The early recordings were produced on but a few tracks so often sub-mixes that contained more than a few elements had to be produced to make room on adjacent tracks. These sub-mixes were intended to be “folded down” to produce the more important mono mixes, so most of the time, in order to produce the stereo mixes, voices and instruments were placed haphazardly left, right and center in what’s best described as “three-track mono” or as was the case with early Beatles albums two track “left/right” mono with the instruments on one side and the vocals on the other, which produced a totally unnatural perspective.

In the early days of stereo having different sounds coming out of two different speakers (plus the “phantom” center channel) was a dazzling novelty making it easy to ignore the disjointed and artificial soundstage, with each of the channels having its own compartmentalized sonic environment. When exposed to the original mono mixes of familiar “stereo” mixes, today’s more sophisticated listeners can easily grasp the superiority of the mono mixes, which have a coherency, solidity and yes, depth of field that make the stereo mixes sound disjointed and far less satisfying.

That is one of the reasons original mono pressings of The Beatles, The Rolling Stones and other groups have increased in value. That said, bass had to be seriously attenuated (“rolled off) and dynamics compressed on those early records so they wouldn’t skip on “kiddie phonographs” of the day.

In fact EMI had an employee whose only job was to play test pressings on all of the “kiddie phonographs” of the day to be sure they would play without skipping. Those that did were labeled (for obvious reasons) “kangaroo cuts” and new lacquers had to be cut with less bass and perhaps less dynamic range.

Records in the recent mono Beatles box have noticeably superior bass compared to the originals and greater dynamic range as well and that too can be expected from The Rolling Stones box since these LPs are made to be played back on today’s high quality record players that can track the lowest bass notes and the widest dynamic range found on the original tapes.

Box Set Production

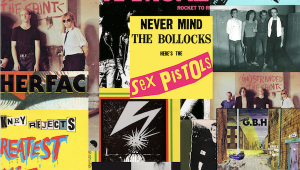

With The Rolling Stones in Mono, ABKCO, which owns the Rolling Stones Decca catalog, gives us, for the first time, the complete English and American Rolling Stones catalog in glorious monophonic sound. We get the albums and the Stray Cats a collection of orphaned “B” side singles, single versions of songs, songs that appeared on hits packages and nowhere else and a few other songs.

More so than The Beatles, The Rolling Stones were a mono band. Unlike The Beatles, they didn’t bother mixing and/or releasing primitive “stereo” versions of their early albums (though there’s a two CD stereo bootleg that’s fun, though at odds with the band’s intentions), and ABKCO has released certain tracks in stereo that previously only appeared in mono.

However, The Rolling Stones in the 1960s was a band that played live in the studio and depended upon microphone distance and instrument placement for a good mix more than they depended upon getting it right in the mix.

If you’re wondering why The Rolling Stones in Mono box set was sourced from the original analog tapes transferred to DSD (single bit, 2.8224 MHz sampling rate digital) and not produced like The Beatles mono box¬—put up the tapes, cut lacquers all-analog— you’ve probably not carefully considered the differences between the two catalogs.

The Beatles were signed to EMI. George Martin was the producer and called the shots throughout most of the band’s recording career. EMI chose the studio (Abbey Road) and EMI chose the engineer. Throughout most of the Beatles’ recordng career, there were but a few of them: Norman Smith, then Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott, though it got more complicated towards the end.

Nonetheless, almost everything was recorded in one studio by but a few engineers and all of the tapes were stored in Abbey Road’s lower level vault where they remain to this day.

The American Beatles release story is more complex, with Vee-Jay handling the first record called Introducing The Beatles (plus singles on Tollie and Swan) and then Capitol taking over starting with Meet The Beatles and eventually gaining control of the Vee-Jay material, which it later released as The Early Beatles.

It was a messy situation compounded by Capitol’s creating new albums with fewer tracks and including singles not included on U.K. albums. But Capitol also changed the sound, adding echo and shifting the equalization, as well as producing “fake” stereo versions of some tunes for which Capitol had only been sent mono versions.

The produce these “new” records, Capitol had to take the tapes they were sent—already copies at least one, perhaps two generations down from the masters—and then copy again to create the cutting masters, while at the same time adding the echo and whatever else they chose to do to make the sound more acceptable (they thought) to the “kiddies”.

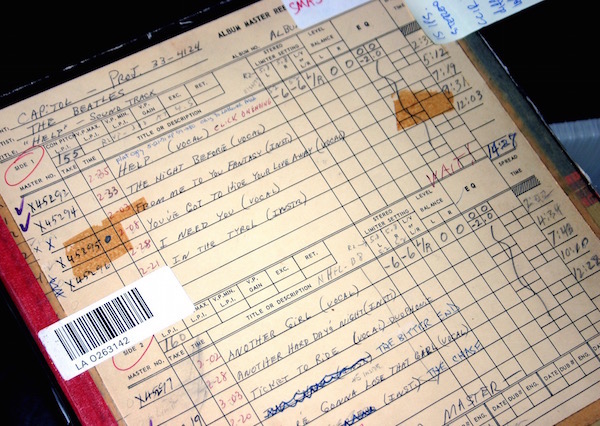

At some point these American masters were probably copied “for safe keeping” with the copy becoming the “master” available for future reissues. A mess! Which is why when EMI reissued the American records on a CD box set, the producers found the sound of the tapes so poor, they were compelled to re-assemble the tracks using the digital masters produced for the Beatles’ stereo CD box set. Here’s a picture of the American Help! master tape.

Note that to produce that one, Capitol had to splice in the instrumentals and that “Ticket to Ride” was in “duophonic” not real stereo, though it’s in real stereo on the UK original. Who knows how many generations down were these tracks used to produce this “master tape”? Is that the one you’d want as a vinyl reissue?

The Rolling Stones

Unlike The Beatles’ relationship with EMI, UK Decca Records did not “own” The Rolling Stones. Instead, Andrew Loog Oldham, having learned the independent game from his mentor Phil Spector, licensed to Decca the Rolling Stones’ recordings, while maintaining control over the content, the production and probably the cover artwork as well (though I don’t claim to know the precise relationship between Decca UK and it’s London American subsidiary).

However, in the UK, singles were never included on albums and four song 33 1/3 rpm, 7” EPs were popular but not so in America where singles were included. This required different track orders, with singles and E.P.s on albums, all of which for the American releases, Andrew Loog Oldham controlled.

That control explains how The Rolling Stones were able to record wherever they wanted, not where Decca told them to record. The first album was probably the only one of the early releases recorded in one studio (Regent Sound Studios, London)—and until Their Satanic Majesties Request, the last one to have identical tracks on both the British Decca and American London releases.

By the second record, they were recording and paying homage at Chess, Chicago and at RCA in Hollywood. On December’s Children (and everybody’s) engineering credits go to Dave Hassinger (Hollywood), Ron Malo (Chicago) and Glyn Johns (London). Starting with Between the Buttons, the group settled in at Olympic for the rest of their time with Decca Records. It Should Be Obvious

Given the cut and paste nature of many of these records, particularly the earlier American releases, attempting to cut lacquers from the original assembled cutting masters (assuming that they still existed) would be as bad an idea as cutting The Beatles Capitol catalog from those later generation “modified” tapes.

The production chain here started with Restoration Producer Teri Landi, who supervised the sound restoration by The Magic Shop’s (RIP) Steve Rosenthal and Ted Young. You can be sure that these old tapes probably had some issues in need of correction. Fortunately, after listening through the entire set, it doesn’t sound to me as if “sound revision” was on their menu.

Landi also gets credit for the analog to DSD transfers (with the ubiquitous Gus Skinas serving as DSD consultant) as well as for tape archives research. No doubt ABKCO got everything on tape and that includes outtakes and alternative takes that had they made it to record instead of the ones on the original records, would prove embarrassing—and that’s happened many times in the reissue business.

The transferred files were then sent to Bob Ludwig at Gateway Mastering for final mastering. What does that exactly mean? It means final file “assembly” and spacing for lacquer cutting as well as making EQ choices when necessary and whatever else Ludwig felt was needed to be done to produce coherency within each record, just as was done to produce the originals. However, Ludwig was not required to attenuate the bottom end, or squash dynamics so that the records would play on kiddie phonographs. He did confirm the major sonic discrepancies from track to track, because of the many recording venues. He emailed this, with permission to share:

“Yes, unlike the Beatles where it was all recorded and mixed basically at EMI and was quite consistent, the Stones were recorded and mixed all over the place and there was very little consistence from track to track. There was one Stones track I worked on that had massive amounts of low frequency rumble from foot stomps and of course the public has never heard it because every time it was mastered it was something that obviously needed to be filtered out. Also, not one bit of echo was added to anything, ever!! It was always there on the mix to be revealed or hidden”.

Once the files had been mastered they were sent (probably over the Internet) to Abbey Road Studios where Sean Magee and Alex Wharton cut lacquers from the DSD files. As best as I can determine, at no time were the DSD files converted to PCM or in any way decimated.

The Uniformity Issue

When original Beatles or Stones albums were released over the better part of a decade, you can be sure the mastering chains used changed over time. These changes affected the final sound of the records—for better or worse—yet in reissuing a decade’s worth of records in a single box and mastering all of them using the same chain, you run into a “uniformity” issue.

Yes, you can EQ each record to resemble the original if that’s your goal, though you’d not want to chop off the bass on the tape or cut dynamics for the sake of “authenticity”, but in the end the sound of the mastering chain will poke through, producing a similar character to all of the records in the box. There’s no way to avoid that, nor is there any way for you to avoid having every record you play take on the character of your system, though of course over time you get acclimated to it and don’t hear it until you hear a familiar record on someone else’s system.

In the case of this Rolling Stones box (and any other box set produced and mastered by one individual at one cutting facility), what you hear is the product of the original tape sound of course, but played back on a particular playback deck, through a particular set of electronics and then cut on a particular lathe through its electronics.

In the case of this box there was one addition step of course, digitization using a particular DSD A/D converter.

Despite the claims of the “digital people” that digital is “transparent”, as anyone can tell you who’s played around with converters and filters, each has a particular sonic signature. So, yes, at first you might notice a particular sonic signature most easily in how the converter deals with sibilants, which produces a particularly uniform “S” sound, but you’ll soon get over that, especially if you take the time to compare original Decca and London (and UK mastered Londons) with these reissues.

There’s really no comparison that favors the originals, unless you are hopelessly nostalgic. When people used to describe these recordings—particularly the early ones—as “dirty”, they were describing more how they were mastered than how they actually sound.

Of course if you’ve not done so I invite you to listen to the Analog Planet Stones Comparison Radio Show. Look, I’ve been playing the originals for decades and as far as I’m concerned, going forward, this box set—despite the “uniformity” issue—is how I’ll be playing these albums. When I compared with the box set reissue, a Decca-pressed “London FFRR” version of Out of Our Heads, the original sounded compressed, cloudy in the midrange and rolled off on bottom.You can compare for yourself at the end of this story. Interestingly, so far as I write this people are preferring the original.

The Artwork

A few YouTube viewers were critical of the cover art based upon seeing the first few album jackets. It’s obvious that ABKCO did not have the original photos for those two, but did for most of the American jackets, which are very well reproduced.

The main offender (no Keef pun intended) is Their Satanic Majesties Request, which is just not accurate—even leaving aside the non-lenticular 3D cover. The picture is sized wrong. The stereo box cover is far better. But that’s the worst one. They got the labels correct in terms of logos and colors (they could not duplicate the originals as EMI could with the Parlophones, without identifying them as ABKCO) and admirably, they left off the bar codes.

A few readers requested album by album coverage but I’m going to have to pass on that. Instead a quick rundown because annotator David Fricke does a very good job with the timeline and analysis in the booklet:

The 1964 debut album (in American called England’s Newest Hitmakers with Buddy Holly’s “Not Fade Away” opening instead of “Route 66” and missing “Mona”) was a set of mostly covers—and for the white American kids mostly unfamiliar stuff —that’s more about high energy and enthusiasm than anything. “Tell Me (You’re Coming Back) is the Jagger/Richards original that lets you know something is happening.

Next to be released in America was 12X5, which was a play on the name of a U.K. only EP titled 5X5. It packed a wallop, containing a combination of covers including Chuck Berry’s “Around and Around”, “Time is On My Side” (most people to this day have never heard Irma Thomas’s gospel-tinged original, from where Keith took the guitar solo note by note), the Womacks’ “It’s All Over Now”, and others but the originals including “Empty Heart”, “Congratulations”, and “Grown Up Wrong” demonstrated a wide range of original ideas. Even though it was a Frankenstein-like patch of “stuff”, for American kids it was really the beginning of their love affair with The Rolling Stones .

Next in the U.K., released in 1965, came The Rolling Stones No. 2 another dark cover—the same one used in American on 12X5. This one was recorded at Chess, RCA Hollywood and Regent in the U.K and like the debut album it’s mostly covers including Allen Touissaint’s “Pain in My Heart”, but it has three originals “What A Shame”, “Grown Up Wrong” (was on 12X5) and the sardonic “Off the Hook”. The version of “Time Is On My Side” here has a guitar intro, the one on 12x5 has an organ intro.

The Rolling Stones Now! was issued in America only as the third Rolling Stones album and again it was recorded in Hollywood, Chicago and in London at Regent Sound. It has the liner notes from the UK No 2, a different version of “Everybody Needs Somebody to Love” than the one on No 2, another Chuck Berry song, “Mona” that was left off of the first album, and has “Pain in My Heart” credited to “Neville”, which was a pen name Toussaint used. It also has three remarkable originals: “Heart of Stone”, “What A Shame” and “Surprise, Surprise” that demonstrated the ability of the group to have original hits.

The fourth American record issued in 1965 was Out of Our Heads, which has another dark-ish cover and a combination of rocked-up covers and originals recorded again in Hollywood, Chicago and London. It lists the engineers finally, Dave Hassinger, Ron Malo and Glyn Johns. It doesn’t get any better than that! The originals include the monster “Satisfaction” as well as “The Last Time” and the flip side of that single, “Play With Fire” as well as “The Spider and the Fly” and the rave up “One More Try”. For American Stones fans, this one felt coherent, even though it was another “cut and paste” job.

Then came the third UK album also called Out of Our Heads but with a different cover that would be repeated in America as the cover of December’s Children (and Everybody’s). The UK Out of Our Heads included songs from the American version plus ”Gotta Get Away” and “I’m Free” plus “Heart of Stone” and the hilarious “The Under Assistant West Coast Promotion Man” who probably knew who he was when he first heard the song. How many kids back then knew what a “promo man” was? Very few you can be sure. This collection was 100% recorded in America in Hollywood and Chicago.

Aftermath released in April, 1966 in the UK and June 1966 in America was the first Stones album featuring only originals and it was also the first since the debut to be recorded in one studio, in this case RCA Hollywood where Dave Hassinger gave the group a pristine, echo-laden sound, similar to Jefferson Airplane’s Surrealistic Pillow. After so many raunchy sounding records, this one sounded like “butta”. The American version had the sitar infused hit “Paint It Black”, which since it was a single, was not on the UK original. The cover art was as different as the track selection and order. The UK version was longer and included “Mothers Little Helper”, “Out of Time” “Take it or Leave it” and the country-ish “What to Do”, none of which were on the American record. The songwriting on this album was on another level entirely compared to previous efforts, especially “I Am Waiting” and “It’s Not Easy” and of course “Paint It Black”. Everyone, but especially Brian Jones, experimented with a wide range of instruments that were in the studio and that added to the quality of the record, which originally was going to be a soundtrack album.

The Stones toured America that summer in support of the album and I took a date to see them at Forest Hills Tennis Stadium. They arrived by helicopter, took the stage and as I remember it (many years ago), when they got to “Paint It Black”—the third song—bedlam broke out, security couldn’t protect the stage and a guy wrapped his arms around Mick Jagger’s legs and attempted to give him oral sex while he banged the tambourine on the guy’s head!

The situation quickly spun out of control and they group exited the stage and left the scene in the helicopter. Or I imagined this but I don’t think so!

Next the group returned to Olympic, which only had a four-track recorder. It was issued in January of 1967 in the UK as the fifth album and in February as the seventh American album. It’s the first Stones album with identical covers for both sides of “the pond”, though there were track differences with the singles “Ruby Tuesday” and “Let’s Spend the Night Together” appearing only on the American version. It’s said to be the group’s first psychedelic outing but the songs really don’t really sound so. “Yesterday’s Papers” sounds like something out of Motown, “My Obsession” has an eastern musical feel, and the other songs perhaps have an unsettled feel but psychedelic? “Who’s Been Sleeping Here” brings out the Bob Dylan in Mick Jagger. The final song, “Something Happened to Me Yesterday” is a quaint, old fashioned thing more associated with Paul McCartney than with Mick Jagger. The back cover cartoon is the most psychedelic thing about the record, which paled sonically compared to Aftermath. With but four tracks much overdubbing and track wiping must have gone on.

In the summer of 1967 Andrew Loog Oldham released in America the compilation Flowers, in the wake of The Beatles Sgt. Peppers Lonely Hearts Club Band. It had tunes left of off the American Aftermath and Between the Buttons plus three never before released tunes “Sitting on a Fence”,”Ride On Baby” and “My Girl”. It also has “Mother’s Little Helper” “Backstreet Girl”, “Have You Seen Your Mother Baby, Standing in the Shadow” and “Let’s Spend the Night Together.” A nice compilation but after Aftermath and Between the Buttons it seemed like album filler. In retrospect, it’s a great compilation!

The Rolling Stones “answer” to Sgt. Peppers… was the ill-conceived Their Satanic Majesties Request, which was a messy, self-indulgent concoction, that had some good moments despite itself, especially “2000 Man and “2000 Light Years From Home”. The true mono mix here is much better than the more familiar stereo mix. You’ll hear.

I’m not going to write about the two “fold down” albums, Beggar’s Banquet and “Let It Bleed except to say there are real mono mixes of “Sympathy For the Devil” and “Let It Bleed” that are superb.

Finally there is the double Stray Cats, which has early and alternative tunes plus singles versions of “Street Fighting Man” and “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” plus the Italian version of “As Tears Go By”, “I Wanna Be Your Man” written by The Beatles for The Stones, “Not Fade Away” (left off the UK first album) and other items of interest for Stones completists.

Conclusion

As I write this, the YouTube video you can watch and listen to below has attracted many comments and people seem to like the original of “Play With Fire” over the reissue. I completely disagree! One person said the reissue sounds “muddy”. Yes if your system can’t cope with the prodigious bass and others think it sounds “cloudy”. I can only tell you that in my system and to my ears, overall the reissues have far wider dynamic range, much better bass, greater transparency and are overall much better. You can also listen to the high resolution files here: