The Byrds Reconsidered : The 1996 Legacy CD Reissues

Expectations were not particularly high. The Byrds consisted of five young men who were complete neophytes at rock music. Given their youth they did have significant experience in other forms of music-folk, bluegrass, choral, jazz- but they were utter enfants in the cosmic vortex of rock and roll. To further reduce their meager chances of success, they chose an awkward, rambling folk song from the then-obscure Bob Dylan to be their A-side. What they did with this roughhewn tune was nothing short of astonishing.

Imbued with a chiming, Bach-like guitar introduction, resplendent vocal harmonies, and an unusual level of lyrical density and ambiguity, "Mr. Tambourine Man" was an instant smash hit. Here was a piece of "popular" music that was light years beyond the cutesy throwaway fluff being played on the radio. Across America, legions of budding guitarists were captivated by the cascading, shimmering sparkle of Roger McGuinn's electric twelve-string Rickenbacker.

Many of us followed the Byrds' music intently over the next few years, and what a wild ride it was. We loved their original "folk-rock" sound, epitomized by "Mr. Tambourine Man" and "Turn! Turn! Turn!." Often, to their commercial detriment, the Byrds persistently pushed and redefined the edge of the art. Buying their records, we were dragged (sometimes unwillingly at first) into jazz, Indian raga, electronic/synthesizer, Latin, South African and (worst of all) country-western music.

Each new Byrds album was a treasure chest, filled with unexpected nuggets of musical ingenuity and innovation: shifting, atypical time signatures, suspended and diminished jazz chords, phasing and backwards tracking, contrapuntal bass lines, modally based guitar leads, unexpected instrumentation ranging from the oboe to the five-string banjo, and of course, immaculately rendered vocal harmonies.

The Byrds' music was consistently savored and praised by critics, and as the recent PBS series documenting the history of rock made clear, their influence on other musicians was and continues to be immense. The Beatles, for example have repeatedly stated that the Byrds were the best American rock group. Remarkably, their thirty year old innovations still resound in today's "alternative" rock. Stars like Tom Petty, R.E.M., Crowded House, and the Gin Blossoms all cite The Byrds as a major musical influence.

Regrettably, the Byrds are a textbook example of what can happen to creative innovators in any art form- they got ahead of their audience. The Byrds' window of commercial success was ephemeral, barely lasting through the year of 1965. The subsequent lack of "the money that came and the public acclaim" (as the Byrds caustically put it in "So You Want to be a Rock and Roll Star") did not deter the group's groundbreaking musical experimentation.

With rare exception-The Beatles obviously- innovation is not the formula for pop music success. The Byrds' music was ever-changing, too complex and "different," too unexpected to be broadly palatable in those days of restricted play lists.

The Byrds can be seen as a folk group going electric in 1965- as Dylan had at Newport before- but instead of alienating a purist audience, they attracted the masses- garnering a number one "pop" hit with "Mr. Tambourine Man" and getting credit for inventing a new musical genre: "folk-rock". After repeating with "Turn, Turn, Turn", the group abruptly changed course with "Eight Miles High" an amazing amalgamation of John Coltrane jazz, and Indian raga set to seemingly innocent lyrics about flying. The Byrds almost succeeded in turning pop music on its ears again, only to have the song banned from the radio as a "drug" song.

In the polemical, politically, polarized year of 1968, the then critically praised, counter-culture underground rock band jettisoned what little commercial base it had left by going to Nashville and recording Sweetheart of The Rodeo - an album of country music! Something went fundamentally awry with the Byrds' commerce-to-art ratio, much to the musical enrichment of their more adventurous fans.

Lack of commercial success didn't stop other musicians from appropriating the Byrds' innovations, repackaging them in a more commercially digestible form, and riding them to success. Although the Byrds may not have reaped rewards for pioneering new musical genres like acid-rock, country-rock, jazz-rock, space-rock, etc., their less talented imitators surely did.

The Legacy Reissues: A Question of Quality

Thirty years after the trailblazing era of the original Byrds, another generation of young "alternative rock" musicians has clearly been influenced. It is only fitting, then, that the Legacy division of Columbia Records, the group's original label, should reissue special editions of the first four Byrds albums. As befitting the Byrds' musical stature, these reissues are meticulously produced, first rate efforts in every way.

A great deal of time, skill and care has been lavished on this project- particularly by producer Bob Irwin-and it really shows. Along with the original material, each disc includes six or seven bonus tracks- all of which has bee digitally mastered using Sony's 20-bit Super Bit Mapping technology. The accompanying boooklets are crammed full of fascinating rare material-group shots, single sleeves, and other memerobilia. Despite the lavishness of the project, the discs cost no more than standard CDs.

Columbia issued The Byrds' canon on compact disc once before, during a time when the new format was mindlessly heralded as "perfect." Nonetheless the label received numerous complaints about the poor sonics. Even dogmatic digital diehards dissented when they compared the CDs to original vinyl.

In October, 1990, Columbia/Legacy released the ninety track The Byrds four CD box set (Columbia C4K 46773). Though certainly a worthwhile addition to the Byrds' catalog, in many ways it was a case of quantity over quality. Many finely crafted songs from the original Byrds were passed over in favor of inferior material from the later "Byrds" of which Roger McGuinn was the only original member.

The poorly conceived package included "New Age"-ish cover art on the four CDs which were given cutesy flight-related titles like "We Have Ignition," and "Full Throttle." Ugh. The unlaminated cover of the 55 page booklet quickly becomes smudged and discolored from finger contact, apparently the result of of someone's efforts to keep costs down on the expensive set . Finally, the audio quality is hampered by the sonic limitations of the conventional digital mastering equipment.

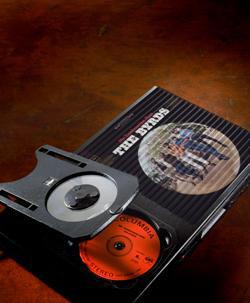

With this set of four, Columbia has more than made up for its original slapdash transfers of historic and important music. Obviously, someone, presumably project director Adam Block, lavished a great deal of time and attention on the supplementary materials. Every aspect of the packaging has been thoughtfully and imaginatively executed- from the original back covers under the CD holders, to the discs themselves, finished in the classic red and black Columbia Records "360 Degree Stereo Sound" label.

Aficionados will relish leafing through the booklets which are packed with fascinating, rare Byrds material, though the pedantic, pompous essays by Rolling Stone's David Fricke, delineating the historical significance of each disc are most unwelcome.

More approachable and informative are the track-by-track comments by John Rogan, author of "Timeless Flight: The Definitive Biography of The Byrds" which is a must-read for those interested in the convoluted history of the group, though I think he should have placed greater emphasis on the the lesser known bonus tracks.

Even more interesting are the marvelous photographs which include alternate, unused shots of the album covers, including the much copied fish-eye photo from the Mr. Tambourine Man album, and the cosmic floating rug from Fifth Dimension . Also included are photos of the original recording session track charts. These indicate the specific contents of each track on the multi-track master tapes. There are even shots of the original tape boxes with handwritten notes on the back. The reissue curators also unearthed the original 45 RPM singles jackets as well as some of the comically dated Byrds guitar music songbooks that were issued in the 60s (such as "The Byrds Bag", featuring a photo of the group stuffed inside an oversized paper bag - I guess you had to be there). Great stuff!

The Sound

it is always interesting to look at the subject of a priori bias in reviews of sound quality. For some so-called "objectivists," the existence of any form of bias renders the reviewer's findings moot, tainted beyond redemption. Unless you are Vulcan or android, it is impossible to completely banish bias or expectation. However, when the observed results differ substantially from the a priori expectations, something significant is probably occurring. In the case of the Byrds reissues, I anticipated some slight sonic improvement, but nothing monumental. After all, how good

can digital renditions of ancient analog tapes be?

To test this hypothesis, I selected four different sets of Byrds source material for careful comparison. Included in my tests were the original vinyl albums, the standard Columbia compact discs, the 1990 box set, and the new reissues. Let the listening begin.

It is not an overstatement to say the I was stunned at the superb sound quality of the Legacy reissues. They are among the best compact disc transfers I have ever encountered. Their superiority over the prior Byrds CD releases is immediately apparent when the two are compared. The reissues sound far more natural and lifelike. They are sweeter, smoother and warmer sounding than the standard CDs (in the way that real instruments and voices are). The Byrds' music is more transparent, detailed and palpable (more "alive" in every respect). Musical resolution is substantially better. The reissues retain fine musical detail that is masked by the standard discs (cymbal parts, guitar picking patterns, subtle

background vocal harmonies, etc.). The overall sound is cleaner, lower in distortion. The reissues offer better spatial separation, focus, and a greater sense of depth and three-dimensionality. Much to my chagrin, they do not seem to offer any improvement in the fifth dimension, however.

By contrast, the standard CDs sound blurred, splattered, harsh, rough, thin, bright, veiled, coarse, flat, and indistinct. Other than that, they are truly wonderful, especially if you don't really like music.

These differences are evident, to a greater or lesser degree, on almost any song on any of the four CDs. Listen to the delineated rendering of the cymbal patterns on "Here Without You" on the Mr. Tambourine Man disc. Or prove to yourself that the Byrds recorded the instrumental core of "Eight Miles High" together, live in the studio. Listen for the distinct rattle of the snare drum head during the bass introduction to this song.

The aural chasm between the reissue and standard CDs is akin to that found between a first generation master tape and second or third generation dub of that tape. The reissues retain a sense of clarity, purity, definition and liveness that is woefully absent in the older Columbia CDs. I should note that gap is not as wide between the box set and the reissue discs. The box set is superior sonically to the original CDs. However, it is no match for these wonderful new releases.

The sonic shortcomings ascribed to the standard Byrds' CDs plague compact discs in general. They can be detected (to some extent) on many, if not most, CDs. Even when the spectral balance is correct (as it generally is on the Byrds' box set), there is a profound sense of incompleteness to the musical presentation. To invoke an analogy I haved used in the past, it is like one of those fill-in-the-dots drawings where the number of dots employed gives only a skeletal representation of the real object. With many compact dics, the music is there in terms of superficial form, but the

rich gestalt of its content is diluted.

On the Start Trek episode "The Tholian Web," our intrepid hero James T. Kirk shifts between two dimensions, appearing apparition-like from time to time to his crewmates. This is how the music on many CDs (including the standard Columbia Byrds discs) sounds. There is enough of it there to tell what your are looking at (Kirk) or listening to (the Byrds), but much of the nuance and detail of real life is absent. Unfortunately, Kirk returns intact from his other-dimensional odyssey. On the original Columbia CDs, the Byrds are not so lucky.

The Legacy reissues restore the music of the Byrds to its original lustrous form. Even without the bonus tracks or the splendid booklet, these CDs would be worth purchasing solely on the basis of their exceptional sound.

At this point, I called a temporary halt to my listening tests. I was so impressed with the sonic calibre of the Legacy reissues that I had to investigate the cause of their unexpected excellence. Was it Sony's 20 bit Super Bit Mapping process? Did the reissues use earlier generation master tapes? Were better ancillary components used in the production of the reissues?

To determine the answers to these questions, I conducted an extensive interview with project producer Bob Irwin. I was pleased (but not surprised) to discover that Irwin is a long-time audiophile who is very conscious of sound quality. He is a long term reader of august journals like The Tracking Angle and The Absolute Sound (which is uncommon for a record producer at this level).

Irwin informed me that all three of the variables cited above affected the sound of the Legacy reissue CDs. Irwin and his staff literally spent years combing through the Columbia vaults in quest of lost Byrds master tapes. In fact they have been conducting a continuous search since the release of the Byrds box set in 1990. They were well rewarded for their efforts. They unearthed a number of original multi-track master tapes (including the legendary "Eight Miles High"), often in boxes labelled as belonging to other artists.

The importance of these tapes cannot be overemphasized. For the original Byrds CD releases, Columbia sometimes had to use second or third generation copies of the original two-track mixdown masters. Even the original two-track tapes were a generation away from the multi-track masters. Some of the first generation two-track masters were worn out (from overuse) or misplaced. So, safety copies (sometimes dubbed multiple times) were used

to master the CDs. As anyone who has analog recording experience can attest, a significant loss of fidelity results from each successive copy.

One hypothesized variable confirmed. The reissues did use higher quality source material than past Byrds CD efforts. What about the equipment chain used to produce the new discs? The brands rattled off by Irwin sound like a Who's Who? of high end audio. The analog tape machines were Cello-modified Studers (the two-track mastering deck was a one inch, 30 ips model). Amplifiers were Levinson and Doug Sax custom tube designs. Speakers were by Dunlavy. Analog-to-digital conversion was via a 20 bit Apogee. Vintage EMT plates were used for reverb (the same models used by the Byrds during the original recording sessions).

Irwin also informed me that the everything was kept pure analog until the very last stage (the inevitable transfer to compact disc). He feels that maximizing the analog component of the process also contributed to the improved sound of the reissue CDs.

So, that's two of the three proposed variables confirmed and accounted for. What about Sony's vaunted 20 bit Super Bit Mapping process? Did it also offer a salutary sonic contribution? Isolating a single variable in a complex, already-completed chain is a daunting task. Toward this end, I asked Irwin to provide me with a list of tracks that used the same source tape on both the box set and the reissues. The box set did not use SBM, while the reissues did. Although this is not a definitive test, it does at least eliminate the potent variable of differing source material.

I carefully listened to the tracks that met the above criteria, concentrating in particular on "So You Want to be a Rock and Roll Star" and "I Know My Rider," both of which were transferred from the original two-track master tapes on both the box set and the reissues. The latter still sounded better, but the difference was definitely less pronounced than on many of the other tracks (which do literally sound like they were produced from different master tapes). Based on the available data, then, Sony's SBM process does seem beneficial.

With the impromptu investigation completed, it was time to return to the listening tests. The reissue compact discs now faced their greatest challenge. For the final round of listening, I hauled out my painstakingly-cared-for vinyl Byrds albums. Although the reissue CDs had easily bested their digital counterparts, how would they fare against their all-analog predecessors? The results from these listening sessions were not so clear cut.

Overall, the albums do sound better than the reissue CDs, although the gulf between the digital and analog representations of the Byrds' music has narrowed appreciably. In general, the reissue CDs suffer from a greater loss-of-information level. More of the original musical performance comes through on the vinyl.

Invoking traditional audiophile parameters, the albums offer sharper, better defined images and image outlines. Each instrument and voice occupies a more distinctly identifiable soundspace. The albums offer superior transparency in that they sound more immediate and present in the listening room, and they retain more musical detail.

The reissue CDs sound slightly veiled, closed-in, dry, flat, and lifeless in comparison. On the other hand, they sound less equalized, more spectrally natural than the albums (particularly the Fifth Dimension pressing I have, which is newer than the other Byrds' albums in my collection). Spectrally, the closest match is between the British album pressings and the reissue compact discs. In general, the Legacy CDs sound smoother and cleaner than the albums.

The most important consideration of all, though, is how well the music itself is conveyed. Here vinyl is still the champion. The ache in Gene Clark's voice on "Set You Free This Time" (from the Turn! Turn! Turn! album) comes across more convincingly on record. On "You Won't Have to Cry" (from Mr. Tambourine Man ), Gene Clark and Roger McGuinn sing the low vocal part in unison. On the LP, Clark's and McGuinn's individual voices are distinctly audible. You can clearly hear the unique sound of each singer in the composite whole.

This is less evident on the CD, which sounds more like two anonymous vocalists singing together. The unique sound of McGuinn's electric twelve-string Rickenbacker guitar comes through

better on the album. This singular instrument sounds more like its real life counterpart on vinyl (I have owned several of these guitars over the years, and know their sound very well).

As good as the reissue compact discs are, they still do not capture the essence of music as well as the anachronistic vinyl albums do. They do come far closer, though, than any previous Byrds' CD releases.

Wouldn't it be great if there were a way to combine the best of both the vinyl and the reissue CDs? Well, there just may be. According to producer Bob Irwin, his Sundazed label is planning to release these four records on ultra-high quality vinyl the first quarter of 1997! I for one can't wait. (we'll cover Sundazed's vinyl reissues another time-Ed)