Kaikhosru Sorabji: Adventures in Extreme Piano

Editor's Note: I am pleased to post this new piece by one of The Tracking Angle's most fearless and original writers, Steve Taylor. When he wrote for The Tracking Angle, Taylor almost always covered lesser known groups and composers. Taylor managed to convey the color, emotional content and meaning of unfamiliar, and often difficult music with great clarity and infectious enthusiasm. With this overview of the composer Kaikhosru Sorabji, Taylor picks up where he left off. We are fortunate to have him back, and hope you agree.

As with the Charles Lloyd piece, because of technical limitations, images of the pianist Michael Habermann and available album cover art will be found in the "Photo Gallery," accessible at the bottom left hand side of the home page.—MF

Kaikhosru Sorabji: Adventures in Extreme Piano

Copyright 2003 Steve Taylor

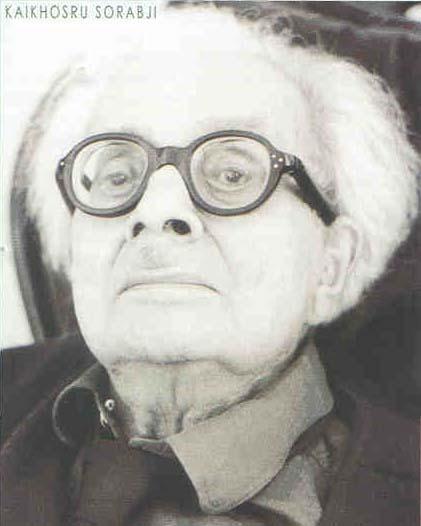

In May 2003, Michael Habermann, Peabody professor of music and classical piano recording artist, released his fifth and possibly final installment of music by composer Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji (1892-1988). Habermann dedicated three decades of his life to the study and performance of Sorabji’s works for piano, and his five recordings, more than any other musician living, has put Sorabji on the map and in music stores for all to taste. Excluding a few recitals in England during 1975, prior to the mid 1970s Sorabji’s music was neither heard nor available anywhere. From a journey that began in 1969, a descriptive survey of Habermann’s historic recordings follows, and concludes with a review of his very latest piano disc for the Swedish BIS label.

Sorabji was a prolific, and, it could be easily argued – extreme, composer of works, focused most on piano and particularly piano solo. He was born Leon Dudley Sorabji, the son of a Parsi father (a Zoroastrian from India) and European mother, and raised in England. An exceptional privately schooled pianist, he was largely self-taught as a composer and regarded himself a conservative romantic. Yet his repertoire, significantly out of step with more atonal explorers of his time, has no obvious predecessor or heir. Somewhat like the music of contemporaneous composer Olivier Messiaen, with which it shares a distinctive organic complexity, Sorabji’s was the product of a seemingly bottomless occidental muse, infused with oriental colors and rhythms, including those of India and ancient Arabia. His music was radically elaborate but consistently rhythmic and even melodious, if melodies are not required to be repetitious nor limited to certain lengths.

Judging by the available anecdotes, Sorabji kept very busy in a private world sealed off well, by design, from unwanted outsiders. He held calling strangers at bay with signs sometimes posted on his domicile, expressing sentiments equivalent to, ‘certain nuns welcome, all others not’. Armed with just pen, paper, piano and privacy, Sorabji would leave a bewilderingly deep legacy of writings, critical essays, and sheaf after sheaf of musical scores -over 100 works in all, some written in a nearly illegible hand, in uncorrected premier-coups drafts.

Piano scores typically utilize two staffs, one staff of notes for each hand to play. Sorabji rarely used less than three and employed as many as seven staffs in constructing works that would prove extravagantly difficult to execute, torturous to memorize and all but opposed to the possibility of attainable musical ends. As he was nearing the age of 40, Sorabji became disenchanted altogether with the imperfect presentations he heard of his performed music, and supposedly withdrew it from the public. And yet, despite the fact that his extant music was not being played or heard, he continued composing, writing music even more formidable than what was already considered unperformable, such as piano symphonies lasting up to 5 hours. He was provided the luxury of such boundless creativity partially through an inheritance that allowed for financial independence.

Though just over a dozen other gifted Sorabji solo recording artists have emerged worldwide, Baltimore-based Michael Habermann has lead with an unrivaled devotion to and musical vision of Kaikhosru Sorabji. By the total recordings issued so far (less than two dozen in all), “K” Sorabji is slowly emerging from his archive lair an artistic machine, a ponderous figure of Johann Sebastian Bach or Frank Lloyd Wright proportions, who designed but also decorated entire castles of art.

Writing about Sorabji’s music proves challenging, as it is hard to condense and generalize so large, lush and divergent a body of work. Therefore, having violated the rule of brevity in reviewing, tedium may be avoided by skipping the next 4000 words and reading the final paragraphs. But for those who have time for the details, here are some impressions of the first four Sorabji/Habermann recordings followed by a review of the new Transcriptions album.

[Note: The first three titles were reviewed from new digital LP originals, which remained, up until very recently, available as CDs, for which the catalog data only is cited. Though the three premiere MusicMasters/Musical Heritage Society recordings are temporarily out of print at the time of this writing, I have newly learned that reissue is already under way. British Music Society is planning to release a 3-CD boxed set by the end of 2003. All of the review recordings are digital masters with serviceable sound for the format.]

Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji

A Legend In His Own Time

Michael Habermann, piano

MusicMasters MM 60015 T

www.musicalheritage.com

The first commercial recording ever made of the piano works of English-Parsi recluse K.S. Sorabji, was initiated by a Paris-born citizen of Mexico and the US, Michael Habermann, in 1976, after he secured exclusive permission from the then 84-year old composer to do so. The moment was significant because 36 years prior the piano-score creator had informally prohibited further public performance of his own work. With this recording, Habermann simultaneously opened the door, for other curious pianists and a global listening audience, to the private universe of a little known but excessively gifted person. In view of Habermann’s faithful, sensitive, and loving treatment, for author Sorabji, the recitalist’s appearance must have seemed a miraculous blessing, a delight and grace arriving from beyond his earlier proclaimed ‘granite tower’ of seclusion.

The 1980 album presents six world premiere recordings and 45 minutes out of Sorabji’s vast warehouse of scores numbering in the tens of thousands of pages and hundreds of hours, that had been accruing since 1914. The six catalog selections are well-fitted together here as an attempt to offer a sweeping glimpse of Sorabji’s early range of passions. If a thread can be detected amidst this spectrum, it is that of fantasia, that is, compositions of no fixed form, of structures based arbitrarily upon the composer’s fancy.

Habermann begins, of all places, with the infamous “Opus Clavicembalisticum” (1929-1930), a work cited at one time during the 20th century as the world’s longest ever written for piano. But instead of all four hours, Habermann mercifully provides a smart hologram of the first thirteen minutes, and a sufficient sample it would seem to be. When unabridged, OC is an orgy of such magnitude that no experience metaphor exists to hint its dimensions (though it does foretell the duration and pitch of a typical mushroom dream. Amazingly, not one but two complete recordings by others are available in the year 2003.) The immediate sense of OC is graveness. Within the first minute, after slipping through the vortex into a mundus invisitatus, we have had the idea of climax or resolution already obliterated. OC sometimes features hammered chords, relating a sense of cosmic commotion or superhuman feats of ardor, a repeated bubbling up to a plateau of unceasing wave-like cataclysms. Though the first 5% here does have lulls and segue ways of reduced density, it struck me as something not interested in causing the pianist or a listener, to be relaxed. Yet, as precisely argued and intense as the music is, it also contains an expansive openness, free of horizons and is generous in this regard.

A comparably long work, the “Fantasie Espagnole”, follows, which is far more melodic, swinging and romantic than ‘the opus’. It has an unmistakable Spanish character, with many vivacious yet also tender processions, like witnessing an evening of ballroom dances among the gentry of Madrid.

Four much shorter pieces are added to the presentation including the new rhythms and piquant colors of the “Toccata” (1920) and the abstract “Fragment” (1925, rev 1937). There is also the “Pastiche: Habanera” (1922), a grotesque ornamental hybrid of Bizet’s memorable tune from the opera “Carmen”. In the case of the latter, a sort of remix is witnessed that seems darkly humorous even at the same time it is unthinkably spectacular. All three offer a vision of a not quite alien, but liquid aesthetic, as though the idea of madness could be intricately worshipped.

It is in the floating, lyrical “In the Hothouse” (1918) where treasure turns up and which would roughly locate to some extent the future of what in Sorabji’s outlandish output might have wider and general appeal. Here, there is still plenty of decoration but things have been slowed to a more contemplative pace. This area is night-colored. If Sorabji may be offering glimpses of languorous beauty, a portrait of a room jungled in orchids, “In The Hothouse” might just as likely resemble stunning slow motion-picture studies of icebergs emerging from fog. Only here does Sorabji’s pen seem humble, as if made gentle by divine auspice. Although this “nocturne” has the most allure and import for the casual listener, it is not entirely free of a hovering uncertainty.

It should be noted that the years that span the selected album pieces coincide with those when his music was in publication (before ‘the ban’, around 1930), when Sorabji was still in his thirties. If wizened eldership had meaning for the composer, these exercises in maximum texture might prove those of an incessant mind still youthful and untempered by economy of means and other discernment of what is considered ‘enough’ in composing. Given such, the early works of the first record temptingly begin the case toward a complete unveiled repertoire.

Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji

Le Jardin Parfumé

Michael Habermann, piano

MusicMasters MMD 60019 Y

www.musicalheritage.com

Two years later (1982) Habermann and his producer, the pivotal Sorabji advocate Donald Garvelmann, delivered a second recording of four more world premieres to MusicMasters. Focusing exclusively (with one exception) on the iridescent yet still highly ornate calm of the nocturne style, two long works of approximately 20 minutes apiece are presented, each inspired by a figure of the 15th century. The “Nocturne: (Djâmî)” (1928) - after Persian scholar, mystic and poet Abd ur-Rahman Jami, and “Le Jardin Parfumé, Poem for Piano”, - after “The Perfumed Garden” (1923), a famous erotic book by the Arabian poet Sheik Nefzawi.

In slower tempi, Sorabji can be more readily observed as a composer concerned with non-repetitive events, somewhat like the unfolding quality of some ballet music. In the nocturnes, Sorabji marks himself a supreme weaver of timeless suspensions. Gestures and unresolving melodies, no two alike, are lined up in series to produce composition. Floated amidst gesture-clusters thick with curving surface is a background of familiar, “normal” two-hand moments of relative hush. During the active phases it is not unusual to think one is listening to three or four hands playing the keyboard at once. With multiple voices speaking, it is difficult to penetrate all rhythm parts and identify which is principally coordinating the flow of interaction. This language refuses to resolve, issuing like serpentine smoke, endlessly, as if one is lost in an unknown paradise, with its constant reports of new information. It is a world that sounds like brilliant improvisation, has no top, no bottom, without a sense of beginning or end, nor a source or a destiny. It is a plausible parallel to the mystic state of dissolved opposites but yet as active a spell as one might imagine of such.

“Djami” pays tribute to the genius for which it is named with what sounds like a humbling telescope pan of the heavens. Throughout the piece Sorabji revisits an austere descending figure, which acts as a baseline, like the black fact of the night sky. But in between these sober tetrads are a series of steeping swells, accreting notes, dramatic tumbling chords and runs, which might easily suggest exploding and condensing star systems, nebulae, vast fields of gas and spiraling dust. It seems to ponder events so far away and unknowable that the music can’t help but become a similar thing of mystery. Heard in a darkened room, even time seems to dilate.

“Le Jardin Parfume” feels by contrast more terrestrial, or reflects perhaps the opposite tremendum, of interiority. Like “Jami”, the black keys of the piano predominate and again without any ready emotional fixations. The music does not seem driven but lumbers hypnotically forward by some inevitable force. It is a place suffused with wonder but that does not open out into something larger. If chemical dreams from inhaled plant smoke gave rise to ancient Near East carpet designs, it is also not far to Sorabji’s here sprawling flatland of entangled surface. A convenient image comes to mind, described by the late hashish connoisseur Terence McKenna: several gem-encrusted turtles crawling over a large Persian rug in the dark. Though it may strike some impatient ears as inane, it is a near half-hour of fabulous and inscrutable elegance.

The short pastiche which separates these two long intoxications, a transcription of Rimsky-Korsakoff’s Hindu Merchant Song “Sadko” (1922), has the same night air but is fitted with a melody on top and rich supporting chord harmonies. The latter suggest something like new shades of dark emerald. The second pastiche, one of two transcriptions of Chopin’s Minute Waltz (1922), sounds like the popular melody seen through a spider-web of broken glass and exclamatized with volcanic eruptions. It seems intended to be comedic, as Frank Zappa or Peter Schickele might contrive, but with a disconcerting (and unwitting?) affection for insanity too. It’s a non sequitur to an otherwise meditative affair. With it, Garvelmann & Habermann seemed intent to wake the listener from any stupor of en-tranced oblivion, or, perhaps prime them for the even more challenging catalog ahead.

Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji

St. Bertrand de Comminges; Prelude, Interlude & Fugue; Valse-Fantasie: Homage to Johann Strauss

Michael Habermann, piano

MusicMasters MMD 60118 W

www.musicalheritage.com

MusicMasters (now defunct) was originally a sister company of Musical Heritage Society, for which the third recording of compositions (1987) would complete its Sorabji catalog. But though it contains the most abstract exercises yet explored, this live concert recording is the best sounding and the most compelling as a musical event of the three. Habermann’s deepening grasp of Sorabji’s method and the presence of an audience, lift his playing to heights of poetry and make the most persuasive and musical case for acknowledgement of Sorabji’s contribution to history’s league of composers.

The concert set begins with the “Prelude, Interlude and Fugue (1920-1922)”, an exercise of vivid contrasts. The Prelude is two and a half minutes of continuous notes running in a sine wave, like some helter-skelter djinn desperate for some kind of relief. Which comes in the Interlude’s nocturne-like pall, whose foreground and background effects, created by differing the volume from each hand, sound like a soul realizing he is no longer alive and having left his body, wonders what is happening, where he is and what now he shall do. This adagio space is spare, gray and indeterminate. The work concludes more actively with a fugue, offering circular forms that waltz up and down the keys, becoming louder, grander, more halting and declamatory toward pieces end. Some kind of release is ultimately achieved though it’s difficult ascertaining to what.

In “Valse Fantaisie: Homage to Johann Strauss” (1925) it becomes apparent how important the performer is to any music score. What might resemble lunacy on paper, a forest of notes, becomes when cogently played, intelligible expressed content. In this fantasy waltz, multiple overlapping and sequential events are witnessed. As the piece plays out, a popular debutante seems forced to complete her entire evenings dance card without reprieve, leaving her exhausted and mad from her many suitors guile and stamina by works end. Though perhaps not a healthy thing to listen to repeatedly, there is no denying Sorabji’s gift for the conveyance of what seems like dance soundtrack, story, and setting, all at the same time.

The album is culminated in the 20 minute long St. Bertrand de Comminges: “He Was Laughing in the Tower” (1941), converging on what might be called an aesthetic of pure piano. Purportedly based on a ghost story, there is a clear avoidance of consonance and pure major key language, and a full admitting to a medley of dark-textured otherness. Around every corner lie new figures, new phrases, one more intricate and unexpected than the next. Jointly they suggest a complete universe unto itself, on its own clock, the credible realm of a disincarnate being? In dramatic sections, Habermann taps out great splashing firmly struck chords, only to dissipate again in patterns of dissolution. It is very entertaining and elusive, a pageant of baffling drama.

Yet through it all, Habermann makes this inconceivably difficult to execute, ultra sophisticated music, more fluid and alive somehow than on either of the first two records. If you were a music buyer on a budget, this Sorabji recording alone would last one years trying to absorb the prodigious quantity of notes and internal logic of what is going on. And yet, the true victual of this more abstract and ominous side of Sorabji’s music remains difficult to isolate. Though there are payoffs of exhilaration, texture and technical amazement, one does not come away uplifted or cleansed, but more like having survived unseen danger – granted, a danger surreal and oddly enchanting. The music here might be best approached as a celebration of piano, the favored instrument, which Sorabji must have envisioned an orchestra unto itself. The piano is, for Sorabji, a device that does not necessarily require compromise, morals or tonics to help its possible heterophonies go down agreeably.

The audio quality of this particular recording is notable, as the recital space is finally given a role in the presentation. The piano has full dimension and shadow, which are missing from the earlier two productions. More importantly, the live audience gives these pieces that electric tension of right here right now, of filling time in an immediate and necessary way, the essence of music.

Michael Habermann

Plays Sorabji: The Legendary Works for Piano

Elan CD 82264

www.elanrecordings.com

A small independent label of international talents called Elan Recordings would make a new case for Sorabji in 1995. And they would hit pay dirt when a national radio broadcast subsequently exposed millions to Habermann’s conservatory labors and Sorabji’s cottage dreams, in an interview aired with the pianist in 1996. The hour of widest recognition yet, long in coming for Sorabji, would prove late however, as he passed away in 1988 at the age of 96. But in the interview, Habermann, a communicator of talent to match his playing ability, offered a tantalizing glimpse of what it was like to meet the composer and to dwell in this heady world of vivifying once forbidden fruit. [Check out www.michaelhabermann.com for this and many other articles].

After years of exploring Sorabji’s available scores and manuscripts, Habermann and Elan would determine that it was the nocturnes that best exemplified ‘legendary’ status. By 1993 Michael Habermann had completed preparations for the world recording premiere of the penultimate, half-hour nocturne “Gulistan” (The Rose Garden, 1940). To this they would add a reprise of “Djami” discussed earlier, first released in 1982. Plus two shorter pieces, though not discernible from the titles, “Quare reliqua hujus materiei inter secretiora” (1940, also based on a ghost story) and “Fantasiettina sul nome illustre dell’egregio poeta Christopher Grieve ossia Hugh M’Diarmid” (1961).

The re-creation of Sorabji’s “Rose Garden” here marks a peak experience among the nocturnes. Habermann is commandingly fluent, like an actor thoroughly disappeared into his role, just as Sorabji, closing in on 50 years of age when he completed it, has moved more confidently toward the white keys. There is still this pervasive feeling of darkness but the long, often luxuriant phrases are gently, soothingly delivered with great ceremony. Sorabji achieves a new kind of musical moment, a unique and fully realized rite, while Habermann’s live concert reading makes a landmark statement of breathtaking splendor. Shown at last, amidst the many thick scores so far, is the energy and reward of nourishing repose that only beauty of such order can claim for its own.

“Quare reliqua hujus materiei inter secretiora”, also from the same watershed year of 1940, is half as long as “Gulistan”, but is slightly more otherworldly. It shares the tenor of earlier, comparably difficult Sorabji pieces, replete with the familiar suspensions of time and unpierced murk but with a greater sense of formal organization. There is less dash, more erudition, like that of literary short story or novelette.

Two complimenting short pieces, both only a few minutes long rounds out the recording. Here, in the miniatures of “Fantasiettina” and Habermann’s own original “In the manner of Sorabji”, something salient appears. Abstract intricacy becomes more meaningful when there is also brevity. As a thoughtfully constructed whole, the recording menu offers some of Sorabji’s most exquisite creations and sets them flatteringly next to work perhaps less amiable but of crucially digestible, miniature length. Unlike the studio takes of the first two MusicMaster discs, all of Habermann’s new attempts here are unmistakably lively and sure, without trace of overly crisp study.

Sorabji: Piano Music and Transcriptions

Michael Habermann, piano

BIS CD-1306

www.bis.se

The latest medley of premiere piano pieces, all save one played from original manuscripts, collects up creative Sorabji interpretations of works by other composers. The six-piece set, balanced as three short and three long, issue from four different decades and together paint a bracing picture of Sorabji’s broad vocabulary of styles. Seen from this hilltop of variety, Sorabji’s principal occupation as a composer emerges most conclusively as what might be called pianism.

Based on the “Barcarolle” from “The Tales of Hoffman” by Jacques Offenbach, the “Passeggiata Veneziana” (Venetian Promenade, 1956) is the most distant from its source. In six movements, Sorabji seems to have nearly synopsized his life of technique in piano. A parade of finery through time, and without pictorial center, Sorabji produces a peculiarly new object that is rich almost exclusively for richness sake. Its all here: open-ended abstractions, extra-concentrated lyric details, multiple voice montage, gently floating nocturnal anarchy, and grand, even oddly majestic dance allusions, packed tightly into 21 diverse minutes. It is understandable that Habermann would declare it one of Sorabji’s greatest compositions, as it strives for maximum novelty with a minimum of overstatement.

“Transcription In The Light of Harpsichord Technique For The Modern Piano of The Chromatic Fantasia of J.S. Bach, Followed By a Fugue” (1940), the album’s headliner, is the opposite. That is, it is most like its templates. Sorabji is here so true to Bach originals (BWV 903 & 948), that it strikes one as abnormally symmetrical, lacking the pluralized dazzle one by now comes to expect. The BWV 903 fantasia is unique among the Bach works and as an earful to begin with, shares some of the flare of Sorabji’s normal effusive habit. But the subsequent Sorabji-matched fugue is made to seem more theatrical, and, true to Bach, concludes congruently on major keys, an extremely isolated event in the available Sorabji score pages. It is refreshing to witness a new flavor however, as the composer tips his lantern on the baroque angst of this famous work from 1720 with what seems like an attitude of feigned seriousness. One wonders whether this and other “transcription” exercises were made for listener delight or as some kind of amusing in-joke among piano virtuosi. Still, the piece is probably the most accessible in conventional terms, of any in the five Habermann albums—perhaps, because Sorabji meddled with it the least.

The Chopin Minute Waltz reworked as “Pasticcio Capriciosso Sopra” (1933) appears here, just as bizarre as the sister version that was included on the earlier album “Le Jardin Parfume”, as well as the continuous note gush of “Variation 56” (1935-37) from Chopin’s Symphonic Variations. But the most poetic piece on the album is the “Quasi Habanera” from 1917, an original composed when Sorabji was age 25. As Habermann is convinced it is no mere student work, his performance is inspired, delivered here as something charming and mature, as if Sorabji was so young he could not yet think to outdo himself. The airy five-minute Habanera is here delectably slowed down, whence intricacy is lustrous and fascinating, rightly on its own terms.

Finally, Sorabji translates Ravel’s “Rhapsodie Espagnole” as a portentous dream of crisis, circus and liberation. During the fourth and last movement there are player piano-like moments, of themes piling up, like a recapitulated blur of memories from the previous 15 minutes. Sorabji might have scoffed at resorting to a mechanical alternative for realizing his idiosyncratic music, if no human being could. Yet his scores seem to have anticipated and even prepared for the super skills that would eventually appear in the pianists of the last quarter of the 20th century, as well as automatic musical technologies such as the Poweroll computer piano that can now easily execute humanly unrealizable music.

~~

After retiring from public performance, Sorabji became entwined preeminently with writing scores. Just as he had coolly labeled earlier pieces (that most others still found hopeless to play), things like, “insipid baby piece” and “trifling”, Sorabji seemed mercilessly content to write on without care if anyone ever played or heard what he imagined. Though he may have known he was creating primarily for himself, the fates would ultimately deny such a strategy. A legend, created by shear personal obstinacy while living, proved in the end too irresistible to be left alone by the curious and talented-enough. The storybook ending is also assisted by the fact that Sorabji lived to a very ripe old age.

For Habermann’s part, Sorabji could not have been luckier to receive such a thoughtful and reverent visitor to his private estate of profuse ink and technical nightmare. The younger pianist went on to achieve something Sorabji himself could have never. Indeed, the keyboard virtuoso ceased performing exactly when, it might be surmised, it became too challenging for even him to render satisfactorily what he had composed.

When Habermann first happened upon this music in a Mexico City book store in the late 1960s, he recalled it resembling “unplayable piano music”. So dense were the scores that a sight-read performance were all but out of the question. In view of this, Habermann resorted to the laborious tack of complete memorization in advance of performance. Around the time Habermann corresponded with and later met Sorabji in 1980, he was told that Sorabji himself could no longer personally memorize the music for performance if his life depended on it! But even beyond the olympic feat of memorization, Habermann seems to have approached it all directly as a fluidity problem! Being accurate to the scores, to every note and rhythm, which make this sound world feel so clock less and quickly sating, Habermann has realized, in all of the nocturnes, and most of the abstract jewelry-like miniatures, unmitigated riches, truly rarified piano experiences.

Sorabji’s piano music is an improbable art, a compounding of florid intensities, one that succeeds in being a multi-faceted and one-of-a-kind world as if these were primary imperatives of its creation. But through Michael Habermann’s ten, always prepared, well-rehearsed fingers and these five albums, could the potent gift of Sorabji’s kingdom, which must be heard to be believed, be at last vouchsafed half a century later. Certainly not for everyone and especially not for those who appreciate the healing silences in music, Sorabji can be seen as an adventurous scout, a test case for what would become physically possible on the piano while holding to an attractive integrity and uniform complexity.

Through all of this realization, Michael Habermann emerges just as large, taking what must have seemed crazy to other pianists, cases of clearly too many notes, and playing them with great dexterity and a recognizable concert rightness. Carefully selected and sometimes prudently trimmed and arrayed, all of Habermann’s readings make Sorabji a sensible, manageable experience. However sometimes daunting, and long the wait been, this music is for those who might appreciate that impossible dream of strange beauty, which only a few human hands have been able to render listenable.