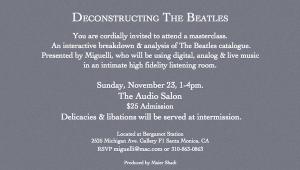

The Origin of The Rarest and Most Sought After Pressing of "Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band"

Mr. Wright tells the story, followed by his interview with mastering engineer Bartley:

It began for all of us differently, and the result was usually the same. For me, it happened during a humid summer day in Tokyo, back in 1969.

To a young boy from San Francisco, Japan was a fantastic landscape. Western fashion had taken hold, but many residents still wore the traditional clothing. Women drifted by in kimonos, their fabric awash in bold graphic designs. Children in school uniforms safely walked the streets alone, cartoon art flourished on every newsstand, and cherry blossom trees lined the streets.

My father was an American advertising executive assigned to Japan Air Lines, and had been transferred to Yokohama. And my mother was a bit of a bohemian - born in Paris during the 1920’s, her parents were members of the Lost Generation. She was happy to be in Japan, but realized we still needed a connection to home. So one hot summer day, we rode a crowded train to a Tokyo theater specializing in American movies.

We arrived and took our seats, the aisles crowded with expatriates. The first film was “Marooned,” about astronauts stranded in space. The special effects were state of the art, with our friends the Russians saving the day at the end. But then the second feature started to roll - the movie was “Yellow Submarine.”

I was transfixed. The landscapes and characters were a radical departure from the usual Disney cartoons, and the vertical Japanese subtitles on the left side of the screen completed the surreal effect. A wide range of cinematic styles and techniques were used to create a strange, bold vision. But it was the music and sound that captivated me.

It was amazing to hear at that age. It evoked a haunting, hallucinogenic world. The soundtrack was a combination of elements – classical, Indian sitar, English vaudeville and psychedelic rock. And when I returned home, I begged my mother for a record player. Soon, a red and white plastic clamshell model arrived, along with a Japanese pressing of Yellow Submarine.

Thus, a lifelong appreciation of the Beatles started for me. Yellow Submarine is one of their more underappreciated albums, but it is still my favorite to this day. I listen to it every few months without fail.

And so, it also began for Don Bartley. One of the top sound engineers in Australia, Don first heard Sgt. Pepper’s…. upon its release in 1967, and decided then and there to enter the music business. As a result,, he eventually came to master what many consider the “holy grail” of audiophile Beatles records: the “Audio-5 Sgt. Pepper’s”.

Yellow Submarine was an extension of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, both in theme and style. And I’ve sought out a number of vinyl Sgt. Pepper’s… pressings over the years – the list includes the current re-masters (stereo and mono), the original UK yellow/black/silver Parlophone (stereo and mono), the UK “one box” and the “two box” Harry T. Moss versions, the original Holland pressing, the Mobile Fidelity standard issue and UHQR, and the Japanese, UK and Australian red vinyl editions.

One rare version has been out of reach: the Nimbus Supercut pressing, said to be one of the best. But in the course my research, I came across a lesser-known Australian audiophile release from 1983, the EMI Audio-5. I have come to realize that, from a sound quality perspective, this may be the most valuable and best sounding of them all.

It was created for the Sydney Audio Show in 1983. A team of EMI Australia executives decided to do a special release of five albums. These dedicated audiophiles and regular show attendees wanted these pressings to be top quality recordings that would highlight EMI Australia’s capabilities as an audiophile label. Given the audience, they knew these pressings needed to be of the highest quality. They had also recently spent millions of dollars to upgrade their facility and create a mirror of Abbey Road Studios, all the way down to the TG mixing board, staff assignments and maintenance schedules.

So they called the home office and relayed their requirements. Abbey Road engineers created a direct 1:1 tape copy of the original Sgt. Pepper’s… source tape —the one and only, with the actual edits spliced and taped together —and called in Don Bartley, by then acknowledged as EMI Australia’s top mastering engineer. They then gave him the freedom to make it sound the way he wanted to hear it. And, using the much vaunted mastering board, they followed what were then considered to be state-of-the-art production methods, including the half-speed cutting process and heavier virgin vinyl. Since this was 1983 and mastering technology had improved since the late 1960’s, the sonic result was said to be spectacular.

Fewer than 500 copies of the Audio-5 album were made. This is fewer than the Nimbus Supercut production run, making it one of the rarest Sgt. Pepper’s… factory pressings in existence. It was never available at retail outlets and was sold only for “cash in hand” at the hi-fi show. And its audiophile provenance makes it all the more desirable.

I know one person who bought a copy during the Sydney show. He still owns it and indicated it has a clarity and immediacy missing in the other analog-sourced stereo versions he has heard.

So to learn more, I decided to contact Don Bartley. Still one of the most respected mastering engineers in Australia, he has an active and thriving business near Sydney called Benchmark Mastering.

BW – So I understand Sgt. Pepper, in fact, got you into the mastering business.

DB – Yeah, for me it was fantastic, because it was one of the very first albums I bought. It was the stereo version, and in fact, I still have that copy (laughs). I heard it for the first time in 1967, and I was mesmerized. At the time, I was working for the government as an electronics technician in training. I listened to this incredible sound coming off that record, and said ‘Wow, what is this?” I was fascinated, and I thought to myself, “I want to do this for a living!”

I had built my own amp, mixer and speakers, so I was already a minor hi-fi buff. But it really got me thinking that I want to get into this business, this process. It was a life changing experience. I thought, “There’s something going on there I want to know more about.” I had albums before that – but this one came along, and it was a combination of everything I had been listening to. Such a clever production - it grabbed me. Inspirational is the word.

So eventually I got a job at the Australian Record Company. I told my parents about my new position, and they said “Oh no! A government job is very secure!” As well, my school careers adviser had suggested being a train driver, or bus driver instead (laughs).

BW - So what was the process like back then?

DB – When I started mastering in 1971, I was told to leave the recordings alone – no EQ or other changes allowed! The priority was to transfer the audio on to the vinyl without distortion. And if you have a good clean vinyl of a traditionally cut record, you’ve got a bit of gold there, because they don’t age. Vinyl is a very accurate physical representation of the audio modulations etched into it.

BW - What kind of training did you have – on the job?

I worked for the Sydney Water Board in their electronic section as a cadet design engineer, looking after two-way radios and telemetry systems. It was quite interesting, actually. It was quite advanced for the 1960s. One day, a component salesman I knew stopped by and said “I was talking to a guy who is looking for someone to help in the mastering department of their record plant – would you find that interesting?” So I went and met Richard Harvey. It was a position in the mastering rooms for international releases from Columbia, Polydor and Warners, as well as some local product. At the time, they had Ampex tape machines, Neumann lathes and Westrex cutters – one was a valve room, and the other was a transistor room.

I basically said “Wow!” and chatted with Richard for a few hours, and he eventually said, “I think we can do something.” So I put my name and number on a piece of paper, and didn’t think anything else of it. He called a week later and said: “When can you start?” My family was cautious about it at the time – “when you get a job with the government, it doesn’t get any better.” But that’s how I started at the Australian Record Company.

BW – What was the first album you worked on? DB - My first job was a Van Morrison best of compilation, and we had to put the master together as well as cut the master lacquers. I had already been editing tape at home, so I gave it a go. Richard said, “no, it’s not good enough” and told me to do it again. He pointed out the level issues and other aspects to me, and then how to do it right. It was a great learning process. The album was released and was quite popular. The facility was then bought by Columbia and became CBS records. Not much difference, but there was a bit more diverse product coming through.

So for five years I was cutting at CBS, with all kinds of fantastic music – ELP, Eagles, the Doobies, product from Europe, from Polydor, Bob Dylan, and all the Columbia classics. In those days we had to master at least four albums a day. You were not allowed to change the sound at the time, but were told to make it as loud and clean as possible on the lacquer master.

Then one day, a producer wanted to be present when the record was cut, and they told Richard they wanted to make adjustments. Robbie G. Porter had just produced an album called Eagle Rock for Daddy Cool, and wanted more bass. We didn’t have much equipment around to do that, but I ended up adjusting the EQ on the tape machine, as well as using a graphic equalizer - that’s how the album was released, and I won my first client. I’ve kept in touch with Robbie, and mastered quite a few projects for him over the years.

Then RCA invested in a new mastering room – they had their own record plant, and were outsourcing their cuts and decided to install their own facility. So they bought the lathe, a Neumann console and a Telefunken tape machine, which was the best in the country at the time, and they advertised the position in the newspaper. I thought that might be nice. So I left CBS – sadly, as I rather enjoyed working there - and I joined RCA using this fantastic equipment they had purchased, cutting ABBA, Bowie and a number of great acts.

And soon, more and more producers wanted to attend mastering sessions. Charles Fisher produced Air Supply, and attended our session with certain requests. Sibilance was always problematic on vinyl, and particularly a song called “Lost In Love” – every time they sang the word “lost,” it was causing problems with the groove velocity, and we were trying to figure out a way around it, to control it manually without affecting other sounds. So one of the engineers sat down in front of the Neumann rack and adjusted the acceleration limiter. He adjusted the threshold every time they sang the chorus, and momentarily adjusted an EQ on certain words as it was coming straight off the ¼” tape.

I also mastered an AC/DC project for the Albert group. Ted Albert attended the session and spent time with me while I mastered the album. I also mastered a direct to disc recording one weekend – Crossfire, Direct to Disc. It was very successful, did very well, and it was an exciting process. Charles Fisher produced that one as well.

BW - How did you end up at EMI?

DB - In the end, RCA decided to close the factory and I was sent to EMI, as I was told they might have a position for me. I now had quite a bit of experience. When I arrived, EMI said they’d heard about my reputation, and were offering me a job. And I said, “Um, what have you heard?” I didn’t know it, but I’d built a reputation - people were listening, saying “Wow, that sounds good.” But I had no idea, as I didn’t get any feedback!

BW - How did you like it there?

DB - I found EMI really pleasant – more musical, less technical. When you’re working in a factory, as I was before, there are production commitments, they needed 8 sides cut a day. I’d get in trouble as I didn’t produce any sides, but I was spending time working directly with clients. But EMI was a recoding studio, and it was all about the music. You could spend a day with a client and it was looked on as a very positive thing. They accepted the fact that clients would sit in while the album was cut. It was part of the deal, but in the other factory situations it was considered a pain.

BW - Sounds like you were more open minded about it.

DB - I really enjoyed working with clients, because I learned a lot from them - just listening to them talk about how they went about making the record, and what they wanted to hear as the end result. Some clients were very technical and specific and others were musicians, and spoke more on a musical, emotional level. I just learned so much from all of them. I never took a course. Apart from Richard Harvey at CBS, who taught me the ground rules - and did a good job of it - I never actually had a formal education in mastering, as there were no courses in those days. I’m not self-taught, but learned from a lot of people around me, and the ones who came before me. BW: So moving on to the Audio-5 Sgt. Pepper, what was that day like – when you first received the tapes?

DB – After a couple of years on the job at EMI, management called me into a meeting. They presented me with these tapes. They said they were special tapes from Abbey Road, and they wanted to produce an audiophile version of the Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album. I was amazed, and said to myself, “This is me? I’m going to work on this album?” It was like a dream coming true.

BW - You certainly got the right tapes! Did you talk with Abbey Road directly, or did they send something to you on their own?

DB – Management had arranged the tapes prior to my knowledge of the project. I remember looking at them and saying: “Wow, especially for Australia?” They obtained permission from Parlophone, and there they were. I was just so lucky.

The other tapes we had in-house dated back to the sixties, from Abbey Road. Not sure what they sounded like, and I think they were okay, but they were getting a bit old. They had been used quite a few times. The original release was so successful they needed to keep re cutting parts to supply the factory with stampers. It was a constant seller - every three months someone would have to recut Sgt. Pepper’s. I never got to do that, but just got to do it once for this special release. They did all the right things, in this instance, for this album.

BW – The million-dollar question – how did those tapes sound?

DB – They were quarter inch 30 IPS tapes. I was amazed at how it corresponded with that first record I had been listening to. I thought it would be more open and detailed, but there was very little difference in terms of those early vinyl recordings, which is a testament to how good they were. That’s the thing about this album – how well it was recorded and produced. And how the tape sounded like the original vinyl issue – there was so little difference. The tape was nearly identical.

The vinyl records at the time were high quality – if you had a good pressing and a good system, it was an amazing representation of what was going on in the performance, and what was meant to be released. Vinyl in those days was capable of very high quality reproduction. Which it still is today.

And when I worked at EMI in Australia, there was an engineer there who had worked at Abbey Road at that time, named Richard Lush – I think he was the original assistant engineer on Sgt. Pepper’s…. He said everything for the original was done in mono, and fully designed around a mono release. They had spent two to three weeks mixing it for mono, and just as they were sending it off, someone came running down from the office and said ‘by the way, we need a stereo mix.’

So I believe they mixed it in two days for stereo. It’s an incredible mix as well, and it’s quite different. Interesting how they did something like that in such a short time. In those days, people were questioning stereo, and saying that mono was still the way to go. In stereo, it’s moving around a bit, which makes it interesting in one respect – but the mono mix is a different experience. And they were using 4 channels of a Studer tape machine, and bouncing it across to achieve the mixes - this is a difficult process.

BW - Rubber Soul had that hard left/right mix – but with Pepper, they mostly got it right.

DB – It’s more artistically correct, and quite a nice atmospheric effect. Whereas with the early Rubber Soul it’s an extreme technical pan, and it just sits in place.

BW – As for the tape itself, what generation of tape was sent to you?

DB - The tape was one generation, a one to one copy of the original. It was 30 IPS quarter inch tape with no noise reduction or Dolby applied. I’ve been quoted as saying it was Dolby, but it wasn’t. The label on the tape box said it was sent directly from Abbey Road. It had all the correct line up tones on it. And I don’t know if you know about the lock groove in side two of Sgt. Peppers – a little recording that they wanted to throw in. That was also included on the tape, so I was able to match up the lock groove effect as per the original, so I was quite pleased with that!

BW - That had to be a bit of a trick to get that lock groove piece in place at half speed.

DB - I made a copy, put it on another tape machine, and when I was watching where the cutter heard was going, and was able to hit “go” on the other tape machine to make it play in the right spot – and it just worked. Don’t know if they did it originally that way - if that was how they planned it, or a pot-luck thing - but it worked. It’s a little bit different, but it’s still in the lock groove.

Those tapes were one generation from the absolute original, and they sounded so good - clean, quiet - just superb, really. They were very nice to work with. For the half speed, I was able to run the 30ips original at 15ips, so the system worked very well to accommodate the dynamic range and frequency response on the tape.

It goes back to the Abbey Road studio and EMI, and the range of people that were involved in making those records. Not just the engineers, but also the technicians that would come in every day and maintain the equipment, making sure it was absolutely top notch, and that everything was working correctly. When they built the Australian EMI studio in Sydney, they based their studio operation on the Abbey Road system. There was a whole hierarchy of people involved in the day-to-day maintenance and production of the studio. I’d been cutting records for ten years before I joined EMI, and so I came in relatively experienced, but I was amazed that every single day, there was a technician in the studio, making sure everything was working perfectly, noting any odd settings. And the equipment was just superb, which is why we have some great sounding albums from that time. Full credit to them for doing it that way!